Column: A good day for the Coastal Commission, and conservation, in Newport Beach

- Share via

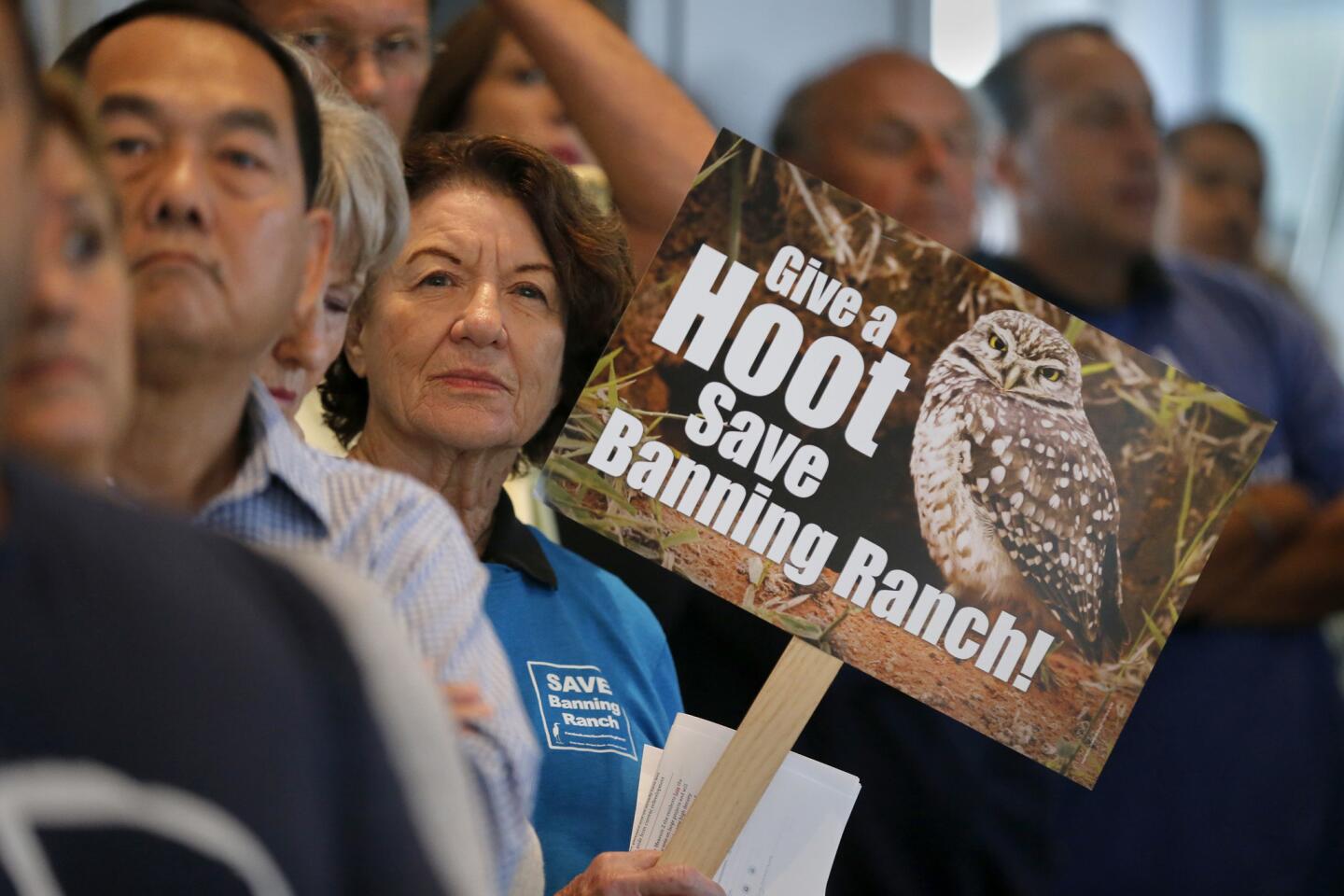

Bulldozers went up against burrowing owls in Newport Beach on Wednesday.

The owls won.

It ain’t over til it’s over, as they say, and it could be years before the battle plays out, possibly in court.

But the bid to build a massive development on a critical coastal ecosystem in Orange County — one of the last of its kind in California — got crushed in a 9-1 vote by the California Coastal Commission.

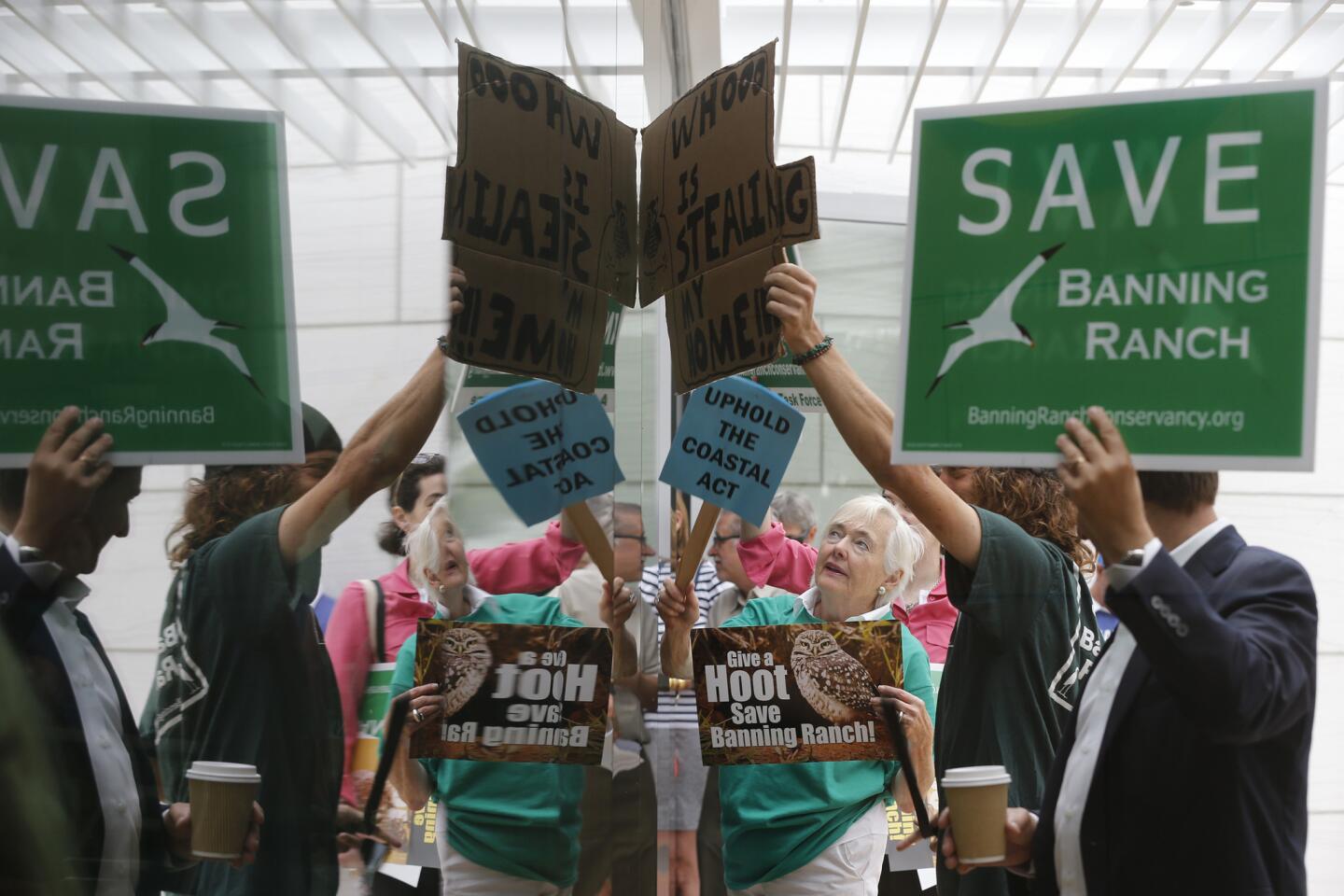

It was a victory for conservationists who have fought the proposal for years, and cheers erupted when the vote came in around 10:30 p.m. after an all-day hearing in which an overflow crowd of hundreds spoke up for and against the project.

“It took 17 years to become an overnight sensation,” said Steve Ray of the Banning Ranch Conservancy, which argued that the project, on an oil field, would have harmed animal and plant life and violated the Coastal Act.

Ray said his group expected to prevail, but not so decisively.

Olga Zapata Reynolds of the group Saving Banning Ranch Together speaks about Wednesday’s vote.

So what happened?

It could be that some commissioners simply didn’t like the project.

It could be that commissioners didn’t like the suggestion that if they did not approve a massive development, developers wouldn’t be able to afford to clean up the environmental damage from decades of pumping oil — damage they caused, and have already been ordered to clean up.

Or it could be that commissioners wanted to stand up to critics who say they fired Executive Director Charles Lester in February to clear the coast for more development.

Or that they were prodded to get tough after some digging by my colleagues Dan Weikel and Bettina Boxall on commissioners’ private, unreported meetings with developers and pressure on the staff to reconsider its assessment that much of the oil field was an environmentally sensitive habitat.

Commissioner Wendy Mitchell, who had said that a vernal pool on the property just looked like a ditch to her, was not present Wednesday for one of the commission’s biggest decisions in years. The public got no explanation for her absence.

Commission Chairman Steve Kinsey was absent, too, having recused himself after reports of private meetings with the developers.

Commissioner Mark Vargas was eight months late reporting a meeting he and several other commissioners had with project opponents, but was allowed by lawyers to vote on Banning Ranch anyway. His contribution at Wednesday’s meeting was to launch a wandering line of questioning about the habits of burrowing owls, only to then snap at — and shoo away — a respected bird expert who stepped to the microphone to help educate him.

Just when you thought there couldn’t be more childish behavior — or a bigger ego — on the dais, Commissioner Roberto Uranga bristled when someone apparently failed to address him as “commissioner.”

But for the most part, commissioners acted like adults, acquitted themselves well and did the right thing. When the vote was in, some of them suggested there might be middle ground between two vastly different versions of what can and should be built on the 401-acre oilfield.

The owner-developers — including big-oil company Aera Energy — originally wanted to build what critics called a small city of 1,375 homes, a resort and stores, promising to clean up and restore the damaged oilfield and open it up to the public. After meeting opposition, the developers later scaled back the project to 895 homes.

But the Coastal Commission’s staff argued that a project of that magnitude would damage the habitat. Based on new evidence of burrowing owls and Native American ancestral sites on the property, the staff last month reduced its own recommendation to 480 homes and called for more open space.

With Wednesday’s decision to reject the larger project, the developers can offer up another proposal in the next six months. Or they can sue. They said they’ll think it over.

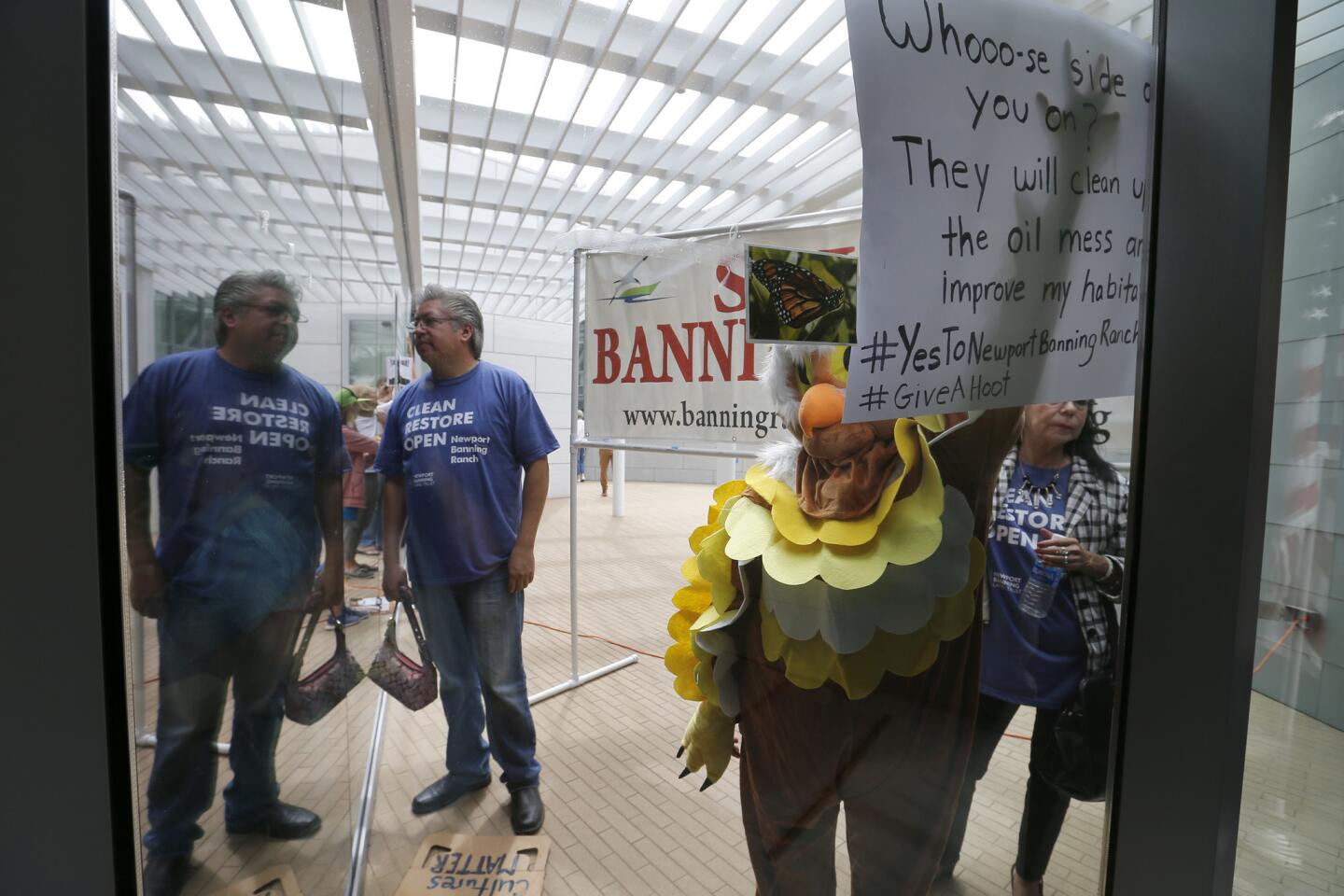

They might also want to rethink the strategy of stacking the room with two or three dozen Aera Energy employees who were transported down from Bakersfield and wore blue shirts that said, “Clean, Restore, Open.”

I asked one if he was from the area. No, he said.

Then why would he care about a housing development in Orange County?

He said he preferred not to comment, and referred me to an Aera representative who said the out-of-towners just wanted to join in with local supporters of the project.

If this were such a great proposal, why would the developer have needed to import supporters for the day?

Like I said, there’s no telling what the next play will be on Banning Ranch, and there’s another contentious, politicized project coming up soon — the proposed Huntington Beach desalination plant.

But Wednesday was a step forward for the California Coastal Commission after months of turmoil, including a power struggle between the commission’s staff of experts and the politically appointed commissioners who have the final say on projects.

Acting Executive Director Jack Ainsworth told commissioners early Wednesday that he had promised them he would always base recommendations on the facts, sound science and the law, and that’s exactly what he and his staff did on Newport Banning Ranch.

Commissioners took the recommendation to heart.

Check back here on Sunday, when I write about the citizen brigade that fought Goliath in Newport Beach, stuck with it for years, and scored a big victory on Wednesday.

Get more of Steve Lopez’s work and follow him on Twitter @LATstevelopez

ALSO

Gov. Jerry Brown signs sweeping climate laws with big changes for California’s future

How Vasquez Rocks, L.A.’s onetime outlaw hideout, became ‘Star Trek’s’ favorite alien landscape

First change to developer fees in 30 years could bring in $30 million more for L.A. parks

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.