Column: In L.A. Unified elementary schools, library books could be off-limits to many students

Here we go again, tumbling down the shaft and into a bizarro world in which school libraries lock out students who need them most.

L.A. Unified elementary school libraries are on the chopping block once again, and library aides, many of whom could lose their jobs, are screaming for justice.

For the record:

8:20 p.m. May 4, 2019Pacoima was misspelled Pacioma in a previous version of this column.

Some L.A. Unified board members, meanwhile, have made passionate pleas to keep the doors open.

“If you’re not reading by grade level by third grade, you’re going to struggle for the rest of your life,” said board member Scott Schmerelson, who has introduced a resolution calling for the district to come up with the necessary funding.

But just a few months after the L.A. Unified teachers’ strike drew strong public support for better pay and more resources for the struggling district, budget woes are forcing miserable choices that will hit students hard.

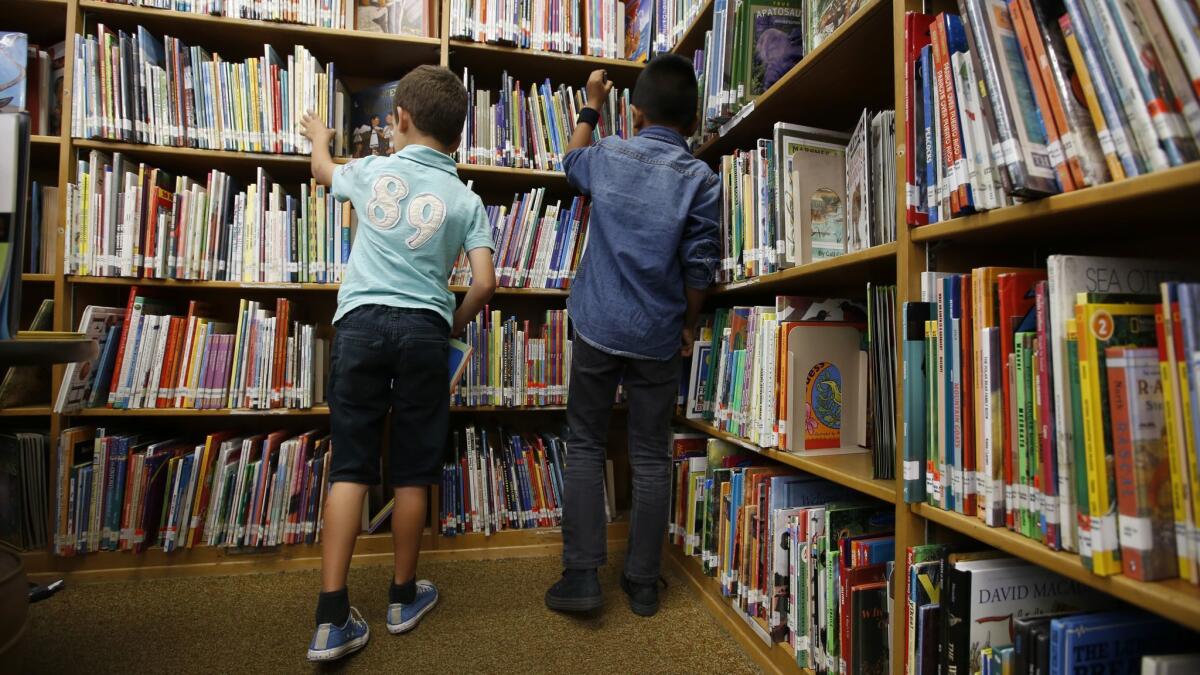

“An elementary school library is one of the more magical places in a child’s life,” said Meredith Kadlec, a second-grade parent who has been writing letters in the campaign to ward off cuts. “Imagination is born from books, and what about the kids who don’t get that enrichment at home? I feel like we’re going the wrong way in America when libraries are at risk.”

They’ve been at risk for years now in L.A. Unified. Many years ago, every school had a fully funded librarian. But as budget problems became more severe, teacher-librarians gave way to library aides, who then got laid off by the hundreds before being rehired. In the recent past, some libraries have been locked up despite the district having spent millions on new books. Typically, elementary school libraries are open only every other week as it is, and aides split their time between two schools.

“If you’re not reading by grade level by third grade, you’re going to struggle for the rest of your life,”

— Scott Schmerelson, L.A. school board member

The strike settlement earlier this year resulted in teacher raises and promises of eventual reduced class size, nurses on every campus, and a commitment to have a teacher-librarian on every middle and high school campus.

But elementary schools got no commitment on library aides. In recent years, those positions — which used to be directly funded by the district — became optional expenses made at the discretion of principals. But those principals have to make gut-wrenching decisions with limited discretionary funds at their disposal. And the needs, in a district in which 80% of the roughly 600,000 students live in poverty and 90% are minorities, always exceed the available money.

At Pacoima’s Telfair Elementary School, where nearly one-quarter of the students have been categorized as homeless in recent years, Principal Jose Razo said he has decided to fund a library aide on Mondays, Wednesdays and every other Tuesday. To do so, he has cut two teacher aide positions from six hours daily to three hours.

That’s typical of the “Sophie’s Choice” decisions made by principals who need social workers, janitors, office aides, tech support, assistant principals and other positions, but can’t afford to pay for everything.

L.A. Unified officials say there is no less money budgeted for elementary schools in the coming year. But the district recently indicated it would no longer cover the health and welfare benefits of teacher aides, as it had in the past. That was seen as an added expense for principals as they drew up their budgets, and they also had to factor in the cost of small raises given teacher aides in the current contract.

By the time complaints led to the reinstatement of district coverage of benefits for the coming year, some principals had already eliminated those positions. Library aide Franny Parrish, union rep for the California School Employees Assn., said a districtwide survey indicated that 132 elementary schools have not budgeted for a library aide in the coming year, although most elementary schools would still have at least part-time aides.

“I’m in [the library] every day and I know what the students want,” Parrish told me at Dixie Canyon Community Charter in Sherman Oaks.

A first-grade teacher joined the conversation to plug Parrish’s contribution.

“Miss Franny reads expressively and brings story time to life,” he said. “She has her own special touch, and the library can’t function if it’s left to other staff. You need someone who’s qualified, and trained, and loves the library.”

Not long ago, in the endless funding uncertainty, Parrish was laid off four times before building up her seniority. You establish relationships with the students, she said, and learn how to nurture individual curiosities. And then you’re gone. She said she’s been in touch with library aides sure to lose their jobs because of low seniority.

“It just makes me want to cry that 10 years later we’re still fighting the same stinking battle,” Parrish told board members at the April 23 board meeting.

L.A. Unified has a $7-billion budget. Library aides make about $11,500 a year, plus benefits, and cost somewhere in the $15-million range.

“An elementary school library is one of the more magical places in a child’s life,”

— Meredith Kadlec, parent

District Supt. Austin Beutner told me that with limited funds available, he wants local school communities rather than the central bureaucracy to make decisions on what will best serve their students.

“All of us believe we should have teacher-librarians and teacher aides in all the schools. All of us. There’s nobody in the community that doesn’t want that,” he said. But with money in short supply, he said, “awful choices” have to be made.

Beutner said the parcel tax measure on the June ballot, which would help fill part of the budget gap, is a chance for those who spoke up in favor of public education to weigh in again.

“I believe it’s time we joined the ranks of Oakland, San Francisco, Torrance, Burbank and Santa Monica, where communities have … provided a measure of local funding for schools,” Beutner said. “Not more money to Sacramento. More money to fund local schools. If we have that funding, we will not be left with a series of poor choices.”

Board chair Monica Garcia spoke to that very issue at the April 23 meeting.

“I appreciate your frustration and your tears,” she told library aides, but she added that compelling arguments could be made by advocates for every job classification that’s underfunded.

“Adequacy is not available in L.A. Unified,” Garcia said, noting that California’s national ranking in per student funding is near the bottom.

“For me,” said board member Richard Vladovic, “a library is a core unit of any educational facility. We need to have libraries. That’s where kids dream.”

The choices are tough, for sure, and they may get even tougher.

But the mere possibility of locking up books in a state that ranks as the sixth-largest economy in the world is an obscenity and a gross disservice to students whose potential we can’t afford to fritter away.

That is the first and last chapter on school libraries, and keeping them open is not an option, but a moral responsibility.

@LATstevelopez

steve.lopez@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.