Legacy projects take shape honoring Lewis MacAdams, poet and crusader for transforming Los Angeles River

- Share via

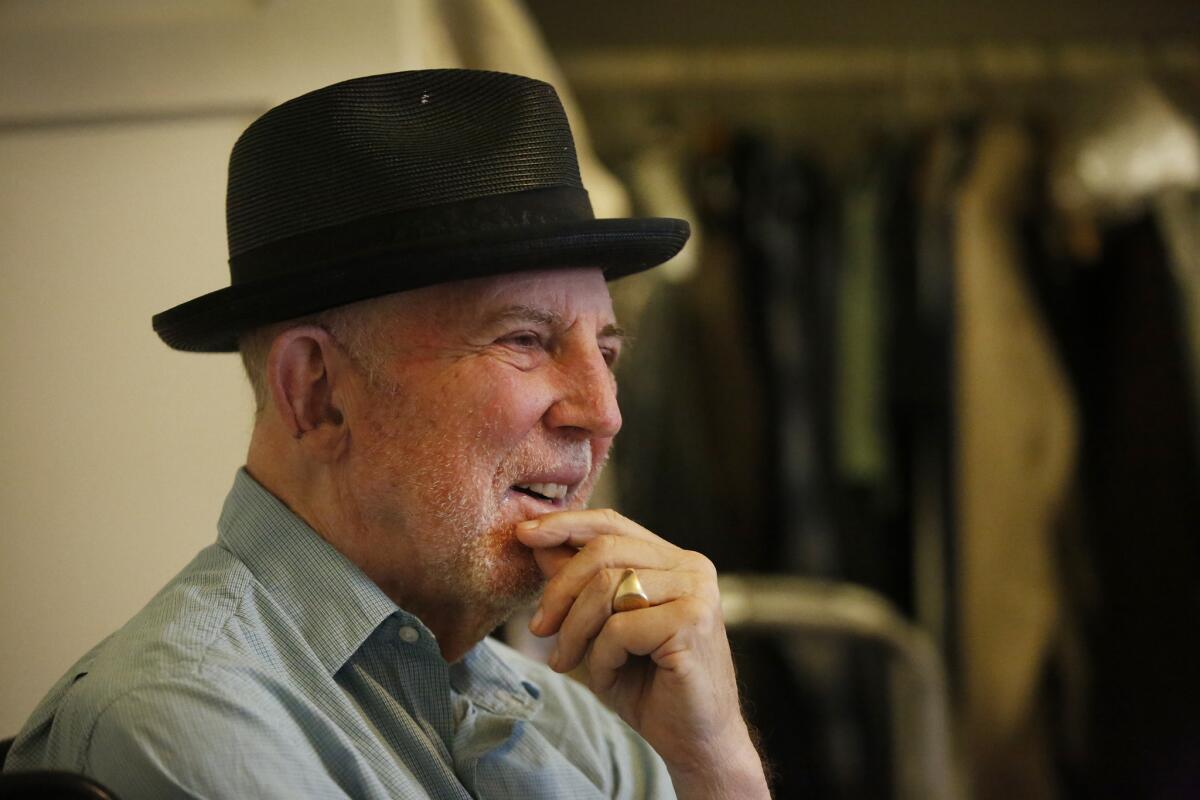

On an early Monday morning, Lewis MacAdams plunged into work on a memoir recounting his years spent crusading to return the concrete-lined Los Angeles River to a more natural state.

It seemed an insurmountable task. His frail body had suffered the toll from a stroke a year ago, and his memory wasn’t what it used to be.

MacAdams, a poet and founder of Friends of the Los Angeles River, looked up at historian Michael Block from his wheelchair and launched into an anecdote. It involved “a little walk I took along the riverbank in 1985 with city officials led by Mayor Tom Bradley — all of whom acted as though it was an odd photo opportunity, or some kind of a joke. Like it was just….”

Suddenly, his words sputtered to a halt. “Sorry,” he said faintly. “I had a brain freeze.”

A moment later, MacAdams, 74, picked up the thread of his tale with a fresh twinkle in his eye: “Looking back, that short walk along the riverbank was incredibly important. It was the moment we went from being spectators to creators when it comes to restoring the river.”

“Look at us now — we’re a snowballin’, steamrollin’, rock ’n’ rollin’ machine,” he continued with a smile and a clenched fist held high.

The hub of MacAdams’ life today is a cramped apartment in a Los Angeles retirement community. Each weekday morning Block uses an audio-recording machine, archival photos and documents to retrace MacAdams’ influence in making river restoration a credible issue for Southern California nature lovers and policymakers from former Mayor Tom Bradley to Mayor

The memoir will be called “Poetry and Politics.” In another part of the city, in a nondescript San Pedro warehouse, another project celebrating the poet-environmentalist’s legacy nears completion.

Sculptor Eugene Daub is finishing a 7-foot-tall monument featuring MacAdams in stark relief over river flora and fauna including frogs, herons and fish. It will be unveiled Saturday at a celebration near the river’s edge at Marsh Park in Elysian Valley.

Daub’s previous works include a bronze statue in Washington, D.C., of Rosa Parks, whose arrest in 1955 for refusing to yield her seat to a white passenger led to a boycott of the Montgomery, Ala., bus system and helped spark the civil rights movement.

Bronze, Daub decided, was not quite the right material for a statue depicting MacAdams.

“Almost everything I do is in bronze,” he said. “But in this case, concrete seemed appropriate since Lewis has campaigned so hard for its removal from the L.A. River channel.”

Michael Atkins, a spokesman for Friends of the Los Angeles River, likes to say the monument is “concrete staring down concrete, and I’d put my money on Lewis’ stony face outlasting that conveyor belt for urban runoff.”

The monument depicts MacAdams, his eyes fixed on a distant horizon. Just beneath the visage is one of his favorite phrases: “If it’s not impossible, I’m not interested.”

In the 1980s, MacAdams pioneered a conservationist campaign by demanding that one of the world’s most heavily industrialized rivers be returned to a semblance of its natural flows from the San Gabriel Mountains to the Pacific Ocean.

MacAdams became known as an uncompromising defender of an often-defiled river.

He helped transform the nonprofit Friends of the Los Angeles River into one of the leading conservationist organizations in California with a list of 40,000 supporters, annual river cleanup efforts and educational programs.

MacAdams and Friends also did much of the work to win approval of a $1.6-billion federal project to restore habitat, widen the channel, create wetlands and provide access points and bike trails along an 11-mile section of unpaved riverbed north of downtown.

“Lewis made the entire region aware of the possibility of making the L.A. River more central to the life of our city,” Deborah Weintraub, chief deputy city engineer, said. “Because of his unflagging commitment to the cause, we’re starting to make that happen for both people and an array of wildlife.”

Block said the memoir is also a work in progress — with new stories only MacAdams could provide being unearthed every time they meet.

“Just the other day, Lewis asked, ‘Did you ever hear about my Tiananmen Square moment?’ ” Block recalled.

“No,” he responded expectantly. “But it sure sounds interesting. I’m all ears.”

“Lewis said, ‘Well, one day, back in the 1980s, I clambered down to the river bottom, raised my hand and stopped a bulldozer in its tracks.’ ”

Block asked what happened next, but MacAdams would not say.

“Instead, he abruptly changed the subject because he felt uncomfortable calling attention to himself,” Block said. “So, the memoir is moving along — slowly.”

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.