A Bay Area battle over a proposed Warriors move from Oakland to San Francisco

- Share via

Reporting from San Francisco — A proposal to move the Golden State Warriors from Oakland to San Francisco’s Mission Bay district has given rise to a NIMBY battle on steroids, a dispute pitting billionaires against billionaires.

The scrum involves world-renowned scientists, a flourishing University of California campus, two of the city’s go-to public relations gunslingers, a nationally known lawyer and, of course, the reigning NBA champions.

Development fights are common in San Francisco — a peninsular city with a long provincial streak, a paucity of undeveloped property and an economy on a tear, fed in part by its $4-billion biotech industry.

“This is sort of a dog-bites-man story in San Francisco,” said P.J. Johnston, a former communications director for then-Mayor Willie Brown who is handling public relations for the Warriors arena project. “The difference is that these are very wealthy dogs.”

Indeed, the tussle has engaged the caliber of titans who wind up with their names on buildings, and who also often run in the same social circles.

Project proponents insist it will bring diversity to a neighborhood dominated by biotech and other life sciences firms clustered around UC San Francisco’s Mission Bay campus.

“I think having the Warriors in Mission Bay is a win-win for UCSF, and the city of San Francisco, and everybody who lives here,” said Marc Benioff, founder and chief executive of Salesforce.com. Late last year he sold the Warriors a 12-acre parcel that neighbors the UCSF Mission Bay campus and a new UCSF children’s hospital that, after a $100-million donation, bears the name Benioff.

Opponents say the development will create traffic chaos and undercut the emergence of UCSF and the district as an international mecca for life science research.

“It’s a terrible idea,” said William Rutter, a pioneer of the biotech industry, founder of Chiron Corp., and longtime UCSF faculty member. He was speaking from his office across a quad from the William J. Rutter Conference Center. “The city itself is a small city, and you have to make choices.”

After purchasing the Warriors five years ago for $450 million, majority owners Joe Lacob and Peter Guber made clear their desire to move the team back to “The City” — as native San Franciscans prefer — where it played in the 1960s as the San Francisco Warriors.

Grass-roots opposition torpedoed an initial bid to build near the Bay Bridge. At Benioff’s suggestion, the franchise next set its sights on two vacant blocks about a mile south that had been intended to serve as headquarters for his cloud-computing company.

The $1-billion, privately financed project would include an arena, two office towers, retail shops and restaurants, public plazas and green space. It would play host to more than 200 events a year — concerts, conventions and conferences in addition to Warriors games.

Organized opposition emerged last spring in the form of the Mission Bay Alliance, led by Rutter and others who were instrumental in developing UCSF Mission Bay.

The alliance is represented by Sam Singer, a San Francisco crisis communications specialist whose clients have included a zoo with a killer tiger and an oil company with an exploding refinery.

He and Johnston have been at it now for more than six months — a battle of sound bites and op-eds and conflicting experts, wrapped in provocative rhetoric about “shadowy” organizations and political intimidation.

See more of our top stories on Facebook >>

::

There is no bay at Mission Bay. The marshy inlet was filled in long ago — with abandoned Gold Rush-era ships, rubble from earthquakes and fires and anything else that might turn water into developable land.

Before World War II, these developed properties supported San Francisco’s port. When the shipping trade relocated to Oakland, Mission Bay became in large measure a neglected brownfield.

In the late 1980s, cramped at its main campus above Golden Gate Park, UCSF began scouting for an additional site. Eventually, Senior Vice Chancellor Bruce Spaulding settled on 43 acres in Mission Bay.

Well-supported by philanthropists, the satellite campus has grown wildly, with its daily population of faculty, staff and students projected to nearly quadruple in the next 20 years. Outpatient visits are predicted to grow from 70,000 a year to 450,000.

Jeanne Robertson, who led fundraising for UCSF Mission Bay, calls the decision to place the arena in Mission Bay “dopey.”

“Those of us in the Mission Bay Alliance have nothing against the Warriors,” she said in an interview. “We just don’t think they should move there.”

In April, Spaulding told a San Francisco business newspaper that the 12 acres should be “land banked” for future campus expansion.

Johnston seized on the comment as evidence that the Mission Bay Alliance was nothing but a front for a few elites accustomed to getting their way in Mission Bay.

“I think the main objection is that the neighborhood has evolved in a different way than they wish it had,” Warriors President Rick Welts said in an interview. “It has evolved in a way that San Francisco has chosen to go.”

Moreover, the alliance was incorporated in a way that did not require disclosure of its financial backers, prompting Johnston to call it a “shadowy super PAC.”

Spaulding and others said the alliance was organized to protect faculty supporters from any backlash — the UCSF chancellor has endorsed the Warriors project — and insist it has growing grass-roots support. Nonetheless, land-banking no longer seems to be the preferred talking point of the project opponents.

Instead they focus on traffic flows and parking, the prosaic fodder of all development disputes. But they also speak of broader consequences.

“The resulting perfect storm of traffic would make it miserable for both the existing neighborhood and for sports fans — in addition to threatening the entire future of UCSF as the center of a world-class academic/biotech/medical complex,” contended a letter to San Francisco Mayor Ed Lee in late September.

It was signed by 20 UCSF professors and researchers, including Elizabeth Blackburn, a Nobel Prize-winning biochemistry and biophysics professor.

Johnston said it was “patently ridiculous” to suggest that the arena might dampen the biotech boom. He produced a letter of support from 12 Mission Bay life sciences companies.

“I don’t think anybody who lives in that neighborhood feels like there’s a terrifying dearth of biotech activity,” he said.

Singer noted that the letter also was signed by the real estate firm that serves as landlord for many of the biotech signees, implying they were pressured.

“This ‘endorsement’,” he told reporters, “is no different than Joe Lacob’s and Peter Guber’s mothers endorsing the Warriors development.”

The project “ran the table,” as Johnston put it, in the approval process, receiving the unanimous approval of a community commission, the city’s planning commission and its Board of Supervisors.

Not surprisingly, Singer discounts the project’s political success, saying it was clear from the start that the city’s approval process would prove to be a series of “rubber stamps.”

FULL COVERAGE: The NFL’s return to Los Angeles

In December, the alliance sued UCSF Chancellor Sam Hawgood, contending he did not have the authority to enter into an agreement with the city and Warriors, surrendering an easement in exchange for traffic plan modifications.

“Sam wanted to reach accommodation for coexistence,” Spaulding said. “Our analysis of everything shows there can’t be coexistence.”

The chancellor, through a spokesperson, declined to be interviewed.

Last month, a more sweeping lawsuit was filed. It contended, in essence, that the review process had been short-circuited in the city’s rush to reclaim the Warriors — in the process imperiling future patients in need of emergency care.

“Some people will die trying to get to the hospital,” the lawsuit said.

It was signed by the alliance’s lead attorney, David Boies, who took on Microsoft, fought for Al Gore in the hanging chad presidential election of 2000, and litigated on behalf of gay marriage.

“Boies,” Johnston said, shaking his head. “Frickin’ David Boies.”

A week later, citing the litigation, the Warriors announced that the projected arena opening would be pushed back a year, to 2019.

The delay probably means three more full seasons for the Warriors in Oakland.

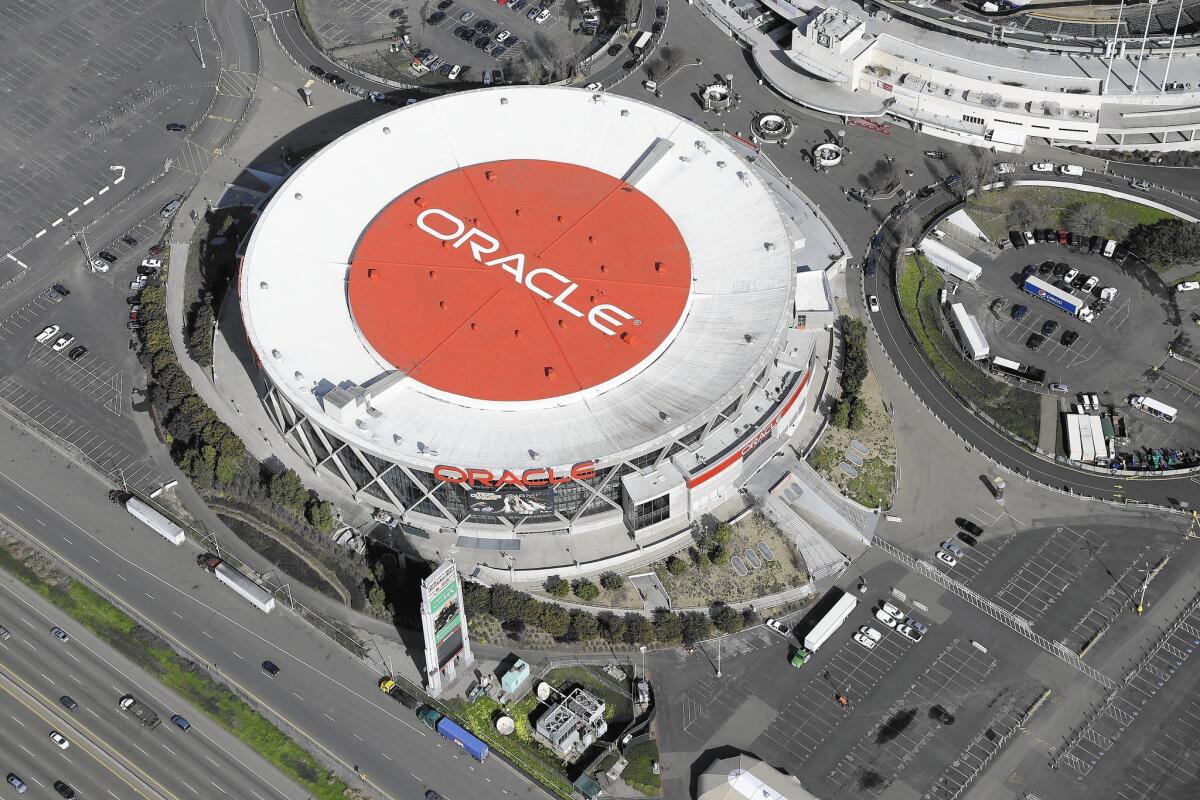

Still, their 40-year run at Oracle Arena can hardly be described as a horror show. For more than 150 consecutive games, dating to 2012, the so-called Dub Nation has filled to capacity the 19,500-seat Oracle — or “roaracle,” as Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf likes to call it.

Though the team store now stocks $85 “classic” San Francisco Warriors sweatshirts, Welts maintains that the franchise is not so much abandoning Oakland as giving its fans and team a facility upgrade.

“Our view is we are moving eight miles,” he said, “and we are still the Bay Area’s team.”

For Warriors players who live in the East Bay, the delay means an extra year to figure out whether they will move to San Francisco or endure a commute across the Bay Bridge to practices and games.

“Everybody is kind of curious to see what the future holds,” Draymond Green, the team’s star forward, said after a recent victory over the Lakers.

He judiciously expressed confidence in the Warriors leadership’s ability to make a new arena a success, but added that for the players, Oracle has its own magic.

“Everybody loves Oakland,” he said. “We will always embrace Oakland.”

Twitter: @peterhking

ALSO

Broncos defense rules in Super Bowl 50 with seven sacks to stop Cam Newton and Panthers

Rams’ Todd Gurley is NFL’s offensive rookie of the year

Former USC standout Ryan Kalil anchors Carolina line for Cam Newton

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.