Brown has last say in labor board dispute between L.A. County, unions

- Share via

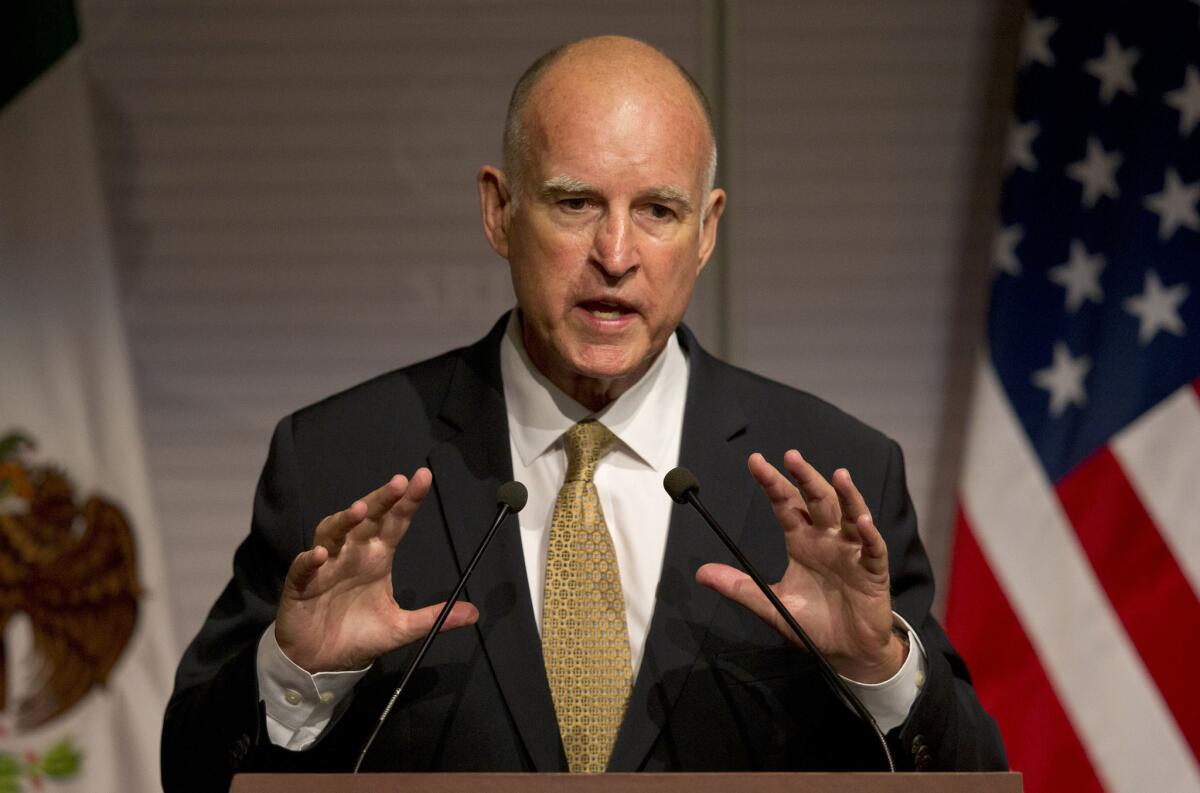

Gov. Jerry Brown has landed in the middle of a simmering feud over who should sit on the independent panels that sort out labor disputes affecting tens of thousands of Los Angeles city and county workers.

A bill that Brown could soon sign or veto would essentially override a decision by the Board of Supervisors to rework how the county’s Employee Relations Commission is appointed.

Under the old system, county managers and union leaders agreed on the selection of all three commission members. The supervisors voted last fall, however, to create a new system that allowed each side to pick one commissioner, with the third selected from a list approved by both unions and management.

Union leaders objected to the change, sparking a standoff that has since halted hundreds of requests for arbitration and complaints of unfair labor practices. So little business has been conducted that before last month’s commission meeting was canceled —like every one since September of last year — the agenda was filled with 31 pages of pending disputes.

Labor unions responded by persuading the Legislature to write and pass a bill to restore their power to screen all three commission appointees. Assemblyman Reggie Jones-Sawyer (D-Los Angeles), the bill’s sponsor, said he wrote the measure because he was troubled by the “politicization” of the city and county employee panels. “If [county supervisors] had not made any changes, the employee board still would be meeting right now,” he said.

Brown has until Tuesday to act on the bill, AB 1881. The measure already has passed both houses. “That’s the power of labor in Sacramento,” said Jim Adams, assistant chief executive officer for the county, which is on record opposing the bill.

The law is written to apply to the city and county of Los Angeles, the only local governments in the state that run their own employee relations panels. The Jones-Sawyer bill also would undo Mayor Eric Garcetti’s recent decision to rescind the process that allowed labor unions to sign off on nominations to the city’s Employee Relations Board. That five-member board recently struck down a plan to roll back pension benefits for thousands of new city employees.

Adams said that in disputes between unions and managers, each side should have the power to select at least one member to such a panel, he said.

“Given labor’s unnecessarily strong objections, it must be their perception that they are giving up some advantage,” he said.

Blaine Meek, chairman of the Coalition of County Unions, said the unions’ aim in pursuing the legislation was to “restore what has been such a successful system for the history of labor relations” in the county.

“We’re not seeking somehow an advantage in this process,” he said. “We’re simply requesting that mutually agreed, established neutrals fill those positions.”

For now, the county’s commission has only one sitting member — the one chosen by management. She is Brenda Diederichs, a former labor negotiator for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority who represented the agency during month-long strikes by transit workers in 2000 and 2003. That means there isn’t a quorum to make any decisions.

County union groups and management blamed each other for the stalemate.

“Labor has refused to meet with management and participate in any way, shape or form, so we never had a quorum,” Adams said. “The management rep shows up every month and there’s no quorum, so business is never done.”

Meek said his group deemed it pointless to appoint a labor commissioner without having the third seat also filled, since votes would likely end up deadlocked. He said management had not proposed any candidates for that “neutral” seat. And when the unions proposed one a few weeks ago, management rejected the pick, he said.

Adams said county management indicated its support for a separate candidate to fill the third seat, but that candidate was rejected by the unions.

Najeeb Khoury, an attorney for Service Employees International Union Local 721, which represents about 55,000 county workers, said the lack of a commission is “a considerable hardship.”

“We can still do certain things, but it still ties our hands,” he said. “It doesn’t allow us to put the county’s feet to the fire.”

Maria Elena Durazo, who heads the powerful Los Angeles County Federation of Labor, has already told Brown’s office of her support for the legislation, Jones-Sawyer said. In addition, he said, city and county employee unions sent representatives to Sacramento “en masse” for each hearing on the bill.

If the governor signs it, or allows it to become law without signing, city and county officials could sue to overturn it, or could choose to fold their employee relations panels and leave those duties to the state.

A spokesman for Brown declined to comment on how the governor plans to act on the bill.

Follow @sewella and @DavidZahniser for more news about city and county government.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.