Few school supplies but a lavish party: At charter school, teachers saw a clash between scarcity and extravagance

- Share via

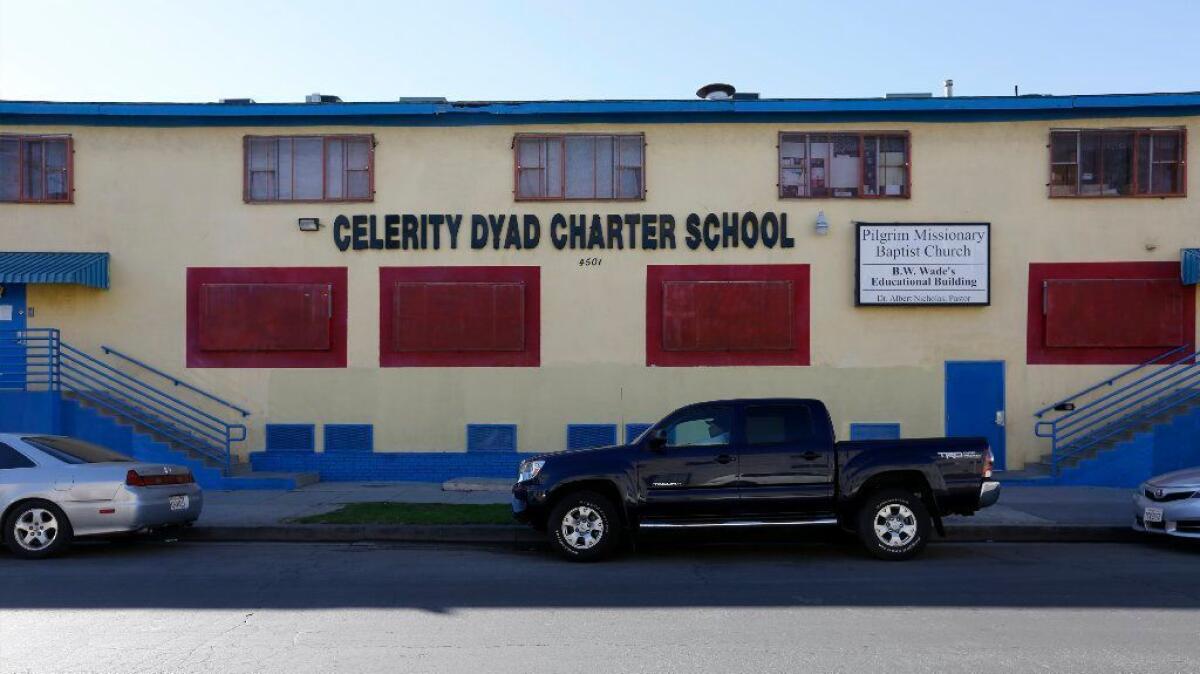

The longer she worked for Celerity Dyad Charter School in South Los Angeles, the more Tien Le wondered where the public money the school received was going.

She taught in a portable classroom on an asphalt lot — not unheard of in this city of tight squeezes and little green space — but her students had no library, cafeteria or gymnasium. The school didn’t provide most supplies, Le said, so when her sixth-graders needed books, pencils and paper, she bought them herself.

Months into her first year, Le and her colleagues were invited by the organization that managed the school to a holiday party at a large house in Hollywood. She and other teachers and staff parked in a lot rented for the occasion and took a shuttle to the house. Inside, there were two open bars, casino tables for poker and blackjack, and a karaoke room. At evening’s end, a limousine ferried guests back to their cars.

“I remember being really confused that night,” Le said. “When I asked for basic supplies, I couldn’t get those things, yet you have money for this expensive party? … For a public school it was not normal.”

When I asked for basic supplies, I couldn’t get those things, yet you have money for this expensive party?

— Tien Le, teacher

Le, 29, left Celerity after two years, in 2012, and is now a doctoral candidate at USC. But she was not alone in her concerns about Celerity Educational Group’s finances. Last week, federal agents with the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security raided Celerity’s headquarters, confiscating computer equipment and records.

The focus of their investigation remains unclear. The search warrants are under seal. But the inspector general for the Los Angeles Unified School District has been looking into allegations of fraud and financial mismanagement by the charter school organization, which runs seven schools in Southern California.

The investigation comes amid a boom in charter schools in L.A., which now has more charter schools than any other U.S. city. They have drawn money and students away from public schools, igniting fears about the school district’s financial survival. Since 2009, enrollment in L.A. Unified schools has dropped by more than 100,000, while the number of children in L.A. charter schools has roughly doubled.

L.A. Unified officials say their investigation of Celerity is ongoing. As part of its review, the district has scrutinized the schools’ founder, Vielka McFarlane, whose salary at one point exceeded that of the superintendent of L.A. Unified. It has also raised questions about Celerity Global Development, a newer entity run by McFarlane that has significant financial and operational power over Celerity Educational Group. Before she opened her first charter school in 2005, McFarlane worked for the school district as a teacher and administrator.

The district’s general counsel has said that the federal investigation is focused not on the performance of Celerity’s schools but on the Celerity organization that manages them, as well as businesses that have relationships with the group.

An associated group, Celerity Schools Louisiana, operates four charter schools in that state. The network had recently been approved to expand into Nevada, but after last week’s raid, state officials there got cold feet and revoked the agreement.

The raid shook the organization. Yet, at a meeting last week for families of students at Celerity Dyad, parents asked few questions and seemed to absorb the news with a collective shrug.

Blanca Magana, who has three children enrolled in the organization’s schools, said she wasn’t at all worried about the investigation. The principal of Dyad, which serves grades K to 8, had assured parents, she said, that “it doesn’t affect the students.”

Charter schools, which are publicly funded but privately managed, are free from many of the regulations that dictate day-to-day life in public schools. Because of this, their supporters often say that they are able to put more money into classrooms and have greater control over how it is spent. Critics argue that they lack sufficient oversight, even as they receive large amounts of public money.

The Times spoke with nine former teachers and administrators in the charter network who said they had long harbored concerns about Celerity’s use of taxpayer dollars and felt that students were being shortchanged.

“There were missing supplies, there was damaged furniture, there were broken light fixtures,” said Christopher Mayes, who was hired last spring as a curriculum specialist at Celerity Lanier Charter School in Baton Rouge, La.

He quit after only three days, disturbed by the conditions and what he said was rampant disorganization. He is suing Celerity Schools Louisiana for unpaid wages and has found new work as principal of a charter school in Memphis, Tenn.

Mayes, 35, said that when news of the raid reached him, he was “not even slightly surprised. I was only surprised that it look that long.”

Former teachers in Los Angeles said that requests for essential classroom supplies went ignored, leaving them with little choice but to spend hundreds or thousands of dollars of their own money. They said, as a matter of practice, Celerity administrators would not hire substitute teachers. If a teacher had to take a sick day, her students would be parceled out to other classrooms, keeping the school’s costs down at students’ expense.

Maurice Suh, an attorney for Celerity, defended the network.

“Celerity has consistently provided necessary resources, supplies and other support for its students,” he said, describing Celerity as “a first-class educational institution.”

Sara Fisher, a former curriculum specialist who began working for Celerity in 2013, said she went at least five months without being paid.

She moved to L.A. to work for the charter network, uprooting herself from Missouri on the promise of a yearly salary of $90,000. But weeks and then months went by, and still there was no paycheck. Fisher, 34, said she dipped into her retirement savings to cover her rent.

“I went to HR and said, ‘I moved across the country for this job,’ and they said, ‘Our hope is to get you paid by Thanksgiving,’” she recalled. “Mind you, I started in July.”

That same year, total revenue for Celerity Educational Group exceeded $38 million, according to the organization’s filings. The majority of it came from public funding. McFarlane, its chief executive at the time, was paid an annual salary of $471,842. Michelle King, the superintendent of L.A. Unified, the second-largest school system in the nation, earns $350,000 a year.

...they said, ‘Our hope is to get you paid by Thanksgiving. Mind you, I started in July.

— Sara Fisher, former curriculum specialist

Fisher didn’t make it to Thanksgiving. In late November, after she pushed for her pay, she said she was called into the organization’s office and told she was being fired for insubordination — not for organizing but for wearing flip-flops during a professional development meeting. (Fisher said she slipped them on only after the meeting in order to be comfortable as she cleaned up the room.) Ultimately, she said, Celerity gave her a check for a fraction of what she had earned.

Asked to respond to former employees’ claims, Suh did not dispute Fisher’s account or Le’s memory of the extravagant holiday party.

“A number of questionable allegations from sources with axes to grind and that go back as far as seven years do nothing to take away from the facts that Celerity schools are accredited by the prestigious Western Assn. of Schools and Colleges and that the majority of Celerity’s schools are California Distinguished Schools,” he said in a statement.

Celerity schools have posted higher test scores than the L.A. Unified average. Last year, 55% of Dyad students who took the state English exam scored at or above grade level, compared with 39% throughout the district.

Although it’s common for schools to emphasize the need for students to perform well on California’s annual exams, former employees said the charter network’s leaders made test scores their singular focus. At some schools, students were tested every Friday, but in classrooms with more children than laptops this task could consume class time for several days. Teachers whose students performed well earned bonuses. Those who did not sometimes were fired, according to former employees.

Celerity management “would go into the teacher’s classroom over the weekend and box up all of their belongings,” Fisher said. “The teacher would show up Monday morning, and they would see all of their stuff just packed up and be told, ‘You’re not going to work today.’”

Some former teachers interviewed said that the charter organization’s leaders also often encouraged them and their students to raise money for causes, a request that struck them as unusual because a significant number of the children lived well below the poverty line.

Le said that one year the network organized a walkathon to raise money to build a school in Africa. Exactly where in Africa wasn’t clear, Le said, nor does she remember receiving progress reports on the school’s construction.

“At the time, I thought it was really cool. I’m glad they’re getting students involved in these international issues,” she said. “I encouraged them to fundraise, which I regret now because I don’t know where it went.”

That was years ago, but the financial demands have continued.

Last year, the network sent out an email asking some of its employees to sell tickets for a gala it was throwing. Each staff member was supposed to sell seven tickets, according to an email obtained by The Times. If they couldn’t hit that number, Celerity would lend a hand.

“Celerity Global is offering installment plans if that will help you meet your goal,” the email said. “Thank you!”

Times staff writer Adam Elmahrek contributed to this report.

Twitter: @annamphillips

ALSO

Tuition hike, budget gaps top agenda as Cal State trustees discuss priorities for 2017

Parents need more help choosing schools in Los Angeles, report says

L.A. school transportation employees fired or pressured to resign for alleged drinking and drug use

UPDATES:

5:45 p.m.: This article was updated to include additional background about the growth of charter schools in Los Angeles.

This article was originally published at 4:00 a.m.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.