The UCLA gymnast who became a viral sensation by just being herself

UCLA gymnast Sophina DeJesus demonstrates how to perform one of her pop-culture inspired moves.

- Share via

Tens of millions of people have seen UCLA senior Sophina DeJesus whip, nae nae and handspring her way to a gymnastics tour de force last weekend. The video of her exacting, exuberant routine during a dual meet Saturday has gone viral, shared more than 450,000 times on Facebook.

In real life, her enthusiasm spreads just as easily. On campus this week, DeJesus stopped everything she was doing to take a picture with two strangers who had seen her performance. “Thank you soooooo much and have a great day,” she told them. She says she’s on “cloud nine” and humbled by the attention.

The knockout routine that captivated the Internet and made her the target of a few unsolicited Twitter marriage proposals is actually the culmination of a long string of losses and setbacks — and springing back from them. There was a fractured back, a broken finger, intense pressure and deferred Olympic dreams. There was also dance class and a TV show along the way.

UCLA gymnast Sophina DeJesus finishes a floor exercise move with a flourish and a smile during practice this week. Internet video of DeJesus’ floor routine at a meet over the weekend went viral.

“I’ve had my ups and my downs. I have been put here for a reason and I’ve gone through my struggles,” DeJesus said in an interview. “What I’ve gone through has made me a better person and my hard work showed in the last meet.”

Those teammates who clobbered her with hugs after she landed her splits? They were primed to do that not because they thought the performance would go viral, but because they had seen her work for over four hours each day to become stronger. They say they felt she had earned her place in the floor competition lineup.

But the real story of how Sophina DeJesus and her smiling, tumbling form ended up on a screen near you the same weekend as Beyonce and the black beret-wearing dancers at the Super Bowl started long before she first flipped. Her grandfather was the president of UCLA’s Afrikan Student Union and helped bring in the school’s first black professor; her mother was a juror in the Rodney King trial.

DeJesus can afford to be buoyant and focused on her sport because of the fights her forebears faced, they say. “It’s embedded in her,” said her grandfather, Webster Moore, a retired Cal State Northridge academic counselor who now teaches meditation. “All these different things that we go through as being the first one in terms of identity — what’s so beautiful about it is, we could be talking about Kobe Bryant or Serena [Williams] ... but when you come up being last, the struggle to be first is biblical.”

She embodies their hopes. He often talks about her like she’s the next Beyonce. “Beyonce, it’s like Sophina as an adult,” he said he thought as soon as he saw the singer join Coldplay during Sunday’s halftime show. “It’s the same moves, the same energy inside, the same calmness, but at the same time to be able to demonstrate all that beauty. When Beyonce walks out, like when Sophina goes on the floor, she is totally in love with movement and spirit.”

Sophina DeJesus is a woman of color in a sport that is still predominantly white. According to a 2007 study by USA Gymnastics, of almost 19,000 gymnasts, nearly three quarters were white, and only 6.61% were black.

She’s proud of the diversity of her team, something her coach, Valorie Kondos Field, has worked to cultivate. But while she is proud of her identity, she mostly talks about the work of pushing her body against the pull of gravity, and deciding when to set race issues aside. “She doesn’t think in terms of being black,” her grandpa says. “All she thinks of is demonstrating her skills.”

“Her father was born in Puerto Rico, her mother is African American,” he continued. “That’s all she can say. What’s her race? All she knows is that she’s a top gymnast.” He paused. “She’s just a beautiful person.”

***

Webster Moore grew up in Alabama, and he and his brother were around the same age as Emmett Till, the black 14-year-old who was brutally murdered in 1955, after he was seen talking to a white woman. Till was visiting Mississippi from Chicago. Two men kidnapped him and took him to a river bank, and forced him to strip naked. Then, they beat him up, gouged his eye out, shot him in the head, affixed part of a cotton gin to him with barbed wire, and threw him into the Tallahatchie River.

For the mother of young black boys in the South, the episode was jarring — jarring enough to warrant a move to the other side of the country. So she put her family in a car and drove to Los Angeles.

Moore finished high school at an L.A. Catholic school, and then went to Los Angeles City College, where he majored in engineering and said he didn’t see people who looked like him. Driven by a desire to see the world, he joined the Navy in 1957. Then he worked for an electronics company, where he recalls getting into trouble for sitting next to a white woman at the dining hall.

Los Angeles was on edge. After Moore left his company, he was asked to teach in Watts, a neighborhood engulfed in riots for six days in 1965 following a controversial traffic stop. He began teaching career skills and electronics to black students, and learned “that it was more of a problem than I thought in terms of race there.”

He eventually went back to college and enrolled at UCLA, where he became president of the Afrikan Student Union. He realized there weren’t any black professors or books on campus that dealt with black history, so he worked on a committee to get Angela Davis hired as the first black professor at UCLA. During his tenure as president of the ASU, four students were killed at Kent State University when National Guard troops opened fire on a group protesting the Vietnam War. Moore wanted UCLA to shut down so students in Los Angeles could support fellow protesters. In a subsequent campus demonstration that turned violent, he got beaten up, and needed 18 stitches to his head.

***

Growing up, Maria Moore saw her father get beaten up as a result of his student union work. It was hard to watch, but she felt able to focus on school in Los Angeles. She attended John Burroughs Middle School, then Los Angeles High School. For college, she went to Cal State Fullerton.

The racial tension the family had once tried to flee followed them. In 1991, after a car chase, a black man named Rodney King was beaten by Los Angeles Police Department officers on the side of the road. Video footage of the beating, first aired by KTLA, stoked racial tensions as it became widely viewed as emblematic of mistreatment by police of minorities. When the cops were acquitted on charges of using excessive force, L.A. rioted once again.

A National Guardsman escorts a Watts resident across rubble-strewn Wilmington Avenue after rioting in 1965.

Under then-President George H.W. Bush, who said that the verdict did not match the video, the federal government convened a grand jury. There was another trial. Maria DeJesus, who was then called Esquibel, the name of her first husband, was tapped as a juror.

What followed was so difficult that her father dropped his pursuit of his doctorate degree to help her. As she assessed the case, memories of her father’s swollen head in the hospital during his student union days flooded back, Moore said. Two of the four police officers were ultimately convicted and sentenced to a few years in prison, but not before the defense tried to pull her off the jury.

She’s worked for the postal service for years, and is now a trustee and steward of the American Postal Workers Union in San Diego.

She met her husband, Jerry DeJesus, on a blind date. DeJesus grew up in New York and New Jersey. His parents were from Puerto Rico and his house was strict and stern. He was in the Navy when a friend told him about a “girl you’re going to love.” He did, and he moved to be with her. They wed 21 years ago. Then came Sophina.

***

From shortly after Sophina was born, she drew attention. Jaw-dropping, judge-stopping attention.

From her family: “I’ve been watching her since she was such a tyke, and she started tumbling,” Moore said.

From her childhood coach, her self-described second mother, Kathy Strate: “No matter what she did, everyone would stop,” she said. “The judges stopped judging and just watched.”

And from Valorie Kondos Field, her UCLA coach, who spotted her in a gym when she was about 10: “Everyone in California knew about this little fireplug named Sophina,” she said. “Everything she does, you can’t help but be captivated by it. Her just strutting across the floor is as captivating as the intricate dance moves that she does.”

She picked up gymnastics young, starting at a club gym. She soon performed at Disneyland.

But despite being a great performer at a young age, there were issues. Sophina says she was a “hyper kid”; in between performances at meets, she would just do backflips on the sideline, instead of being serious. She noticed that parents of other gymnasts told their kids not to talk to her because she didn’t pay enough attention. “I didn’t have any friends then,” she recalls. “I was so sad.”

She told her mother she didn’t want to do gymnastics anymore. It was putting her under stress, Maria said. “People were going crazy over her, they were talking about Olympics,” she said. “It was too much, I took her out.”

From then on, Sophina was in and out of elite gymnastics, a sport with a notoriously short window for success.

***

From a young age, she grew up in a world of two cultures: from her dad, there was Puerto Rican food and salsa music. She started off in a Spanish school, and once it closed, she switched schools. Now, she’s not fluent in Spanish anymore. “I can understand it and speak a little bit but I want to be completely fluent,” she now says.

From her mom, there was dance. Maria started a dance studio called Vibe, and at the time, krumping was in. Krumping is an energetic and aggressive street dance style that originated in South L.A. “That’s like, down down serious,” Maria recalls. “The studio was rowdy. There were contests, and I put the girls in it .… They were right there, krumping with the teenage guys.”

Sophina grew up krumping. As a kid, she danced in a krump battle, and won. It made her feel like someone else. “I had an angry face, and I was really tough,” she recalled. “I felt like I was 6-5 and huge.” Even now, she’s only 5 feet 1.

She started taking more dance classes. In one of her acting and dancing phases, she was discovered by choreographer and entertainer Debbie Allen, who told Sophina’s family that she needed an agent. So she got one, and started doing some TV — she and her sister Savannah wound up on a Discovery show called “Hip Hop Harry.”

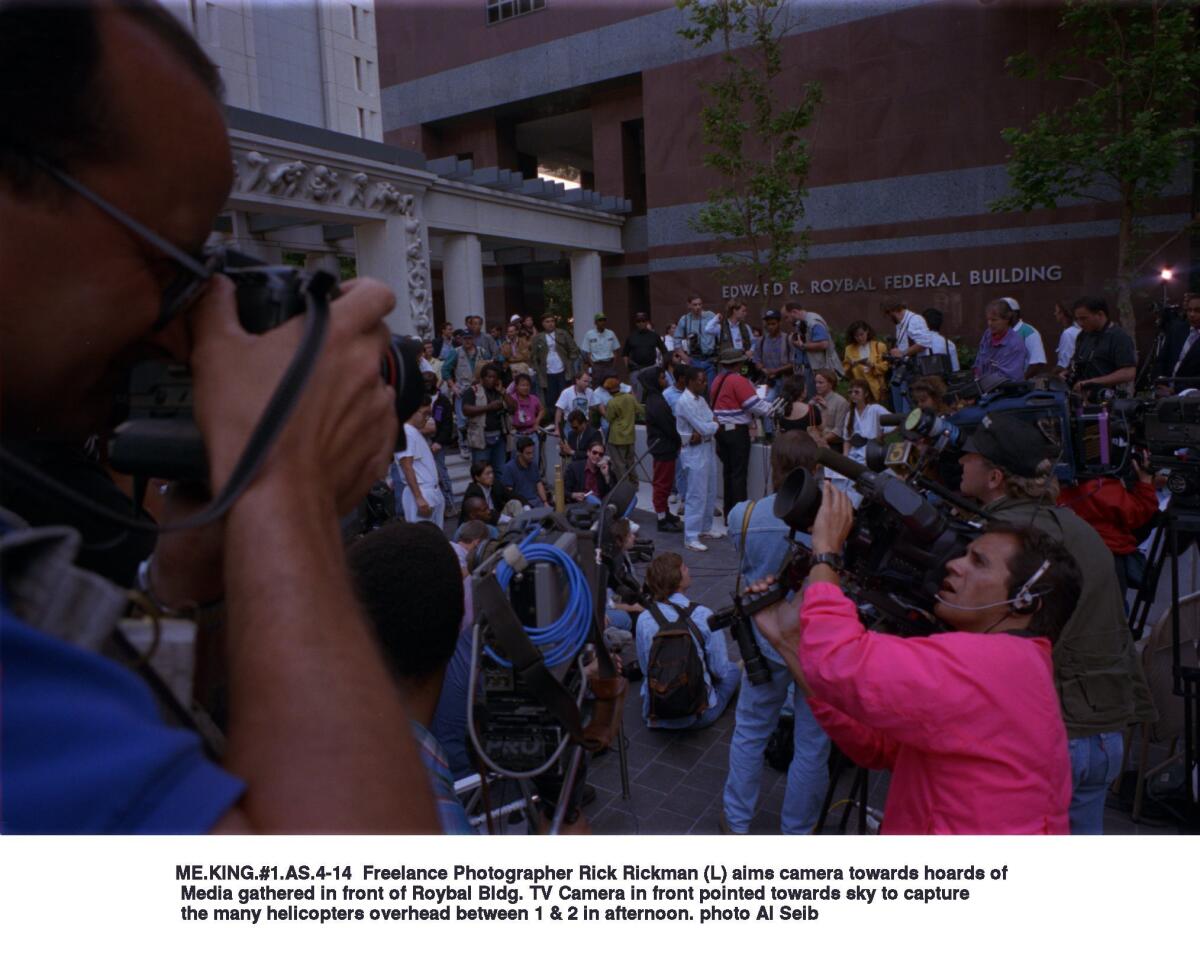

Media and members of the public gather in front of the Roybal Federal Building, where four police officers were being tried in the beating of Rodney King in 1993.

But when she was about 13 she wanted to try gymnastics again. She realized that in gymnastics there was no time to waste, or “you become an old grandma fast.” Her mom thought she had missed the window. But as soon as she tried, people saw her and asked where she had been. Maria home-schooled her for middle school. “Next thing you know, she’s on the USA team,” her mother said. In a junior competition in Japan in 2009, she won the gold medal for her floor routine.

After that win she started training, hard. Then something snapped, only she didn’t know it at the time. Maria could see the pain in her daughter’s eyes, but Sophina was so used to injury that she didn’t know what had happened until a few months later.

It took three doctors to diagnose the pain: she had fractured her spine, and would have to stop training immediately. There was so much pressure, and it hurt Maria’s heart. “She’s in the running for the Olympics, and boom, back break,” she recalls. “This sport is unforgiving and nobody really wants to know how sad it is for us parents to be this way.”

***

A meteoric young gymnast gets home-schooled. She wins gold then breaks her back. Then she starts in her local public high school.

It was hard. The first two years at Temecula Valley High, Sophina was shy. “I didn’t know anyone,” she said. Her mother forced her to open up to people, to ask them what their lunch plans were. By sophomore year, she had her own group. And once she realized she had to stop gymnastics, she joined the dance team, and became outgoing.

Sophina sometimes wanted to straighten her hair, but her mother “was very big on being yourself and never changing who you are,” she says. She was only allowed to flatten her locks for special occasions; otherwise, Maria made her daughters keep it curly. “I thank her a lot for that, and I love my curly hair,” Sophina now says. “She really put confidence in us and told us to make sure you love who you are.”

Miss Val, as she’s known at UCLA, began recruiting Sophina during her sophomore year at high school. For Sophina, UCLA made sense. “It’s in L.A., there’s great weather,” she said. “It has the whole package, we’re amazing at academics and athletics.” Like all the members of the UCLA gymnastics team who receive scholarships, she got a full ride.

***

When Sophina started at UCLA, her mother noticed a change. She became “happy-go-lucky Sophina.” She wanted to have friends and go to the cafeteria. Throughout, she fielded calls from Puerto Rico, which wanted her on its Olympic team. She was receptive, and did the paperwork. But she ultimately decided not to pursue the opportunity. Instead, she focused on school, where she studies sociology and theater.

And she had college gymnastics, which is different from elite gymnastics. College gymnastics is more about entertaining, whereas elite, Olympic gymnastics is more focused on precision in passes. For Sophina, it was the right balance — almost. “I went through a struggle where I ... lost who I really was,” she recalled. “I would fall off the wagon a little and get stressed. It just wasn’t happening.”

She wanted to compete in the floor routine, but there are only six spots in the lineup, and she had to prove that she was ready. Her coach wasn’t sure. “She’s a pretty tumbler, but she’s not necessarily a strong tumbler,” Kondos Field said. “We had to get her strong enough and in good enough shape for her to be able to tumble without deductions. She could do a routine but she wouldn’t outscore someone else in our lineup.”

Sophina spent 3½ years becoming more fit, lean and strong, doing extra conditioning sets. Her coach directed her to attack her weakness, and she altered her diet to build muscle and get stronger.

Suddenly it was the summer before her senior year, and she wanted to graduate with no regrets. This fall, coach Kondos Field saw that Sophina was ready to compete in the floor exercise — but then she had another setback. Sophina broke her finger in preseason and it was hard to stay motivated. After that healed, she tried again -- only to sprain a muscle.

As she healed from that injury, she took more hip-hop classes and spent winter break working with her sister Savannah, now a computer science and engineering student at UC Merced, on her new routine. First, there was the music. She spliced together three songs but had to make sure the beats would still sync up once the words were removed, a competition requirement. Then, they collaborated on choreography, borrowing from the classes. Savannah would propose a risky hip-hop move, and Sophina would tailor it to the world of gymnastics. “Remember, I have to open my legs in a leotard!” Savannah recalls her sister saying in response to one proposal.

They saw the routine as an expression of themselves. “It’s more culturally black, but it wasn’t aimed to be that way,” Savannah says when asked about it. “This is us, this is what we’ve been doing since we were little. It definitely shows Sophina as a person, her crazy and happy self.” Sophina says she expresses both sides of her identity in her floor routine, and that there are Latina hints in her hip-hop.

UCLA gymnast Sophina DeJesus finishes a routine on the balance beam during practice this week.

When she came back from break, Kondos Field cleaned the routine up. She sought what she calls “clean pictures:” Fun hip-hop moves are fine, but legs have to be straight or bent — and not in an in-between position that looks messy.

The day before the weekend’s meet, she made one critical switch, reordering two of the passes, so that Sophina could start strong and end on her easier move: a back layout with 1½ twists to a punch front flip in a layout position. It’s a series that combines two airborne flips in a row; in one of them, the body is rotated not only vertically, but also horizontally. Sophina went from that pass straight into a split, the force creating a thud as she hit the mat.

**

In the moments leading up to Saturday’s competition, a dual meet against Utah, Sophina’s family was nervous. After years of watching her toggle from triumph to injury and back again, it was hard to think about her returning to the floor.

Floor exercise used to be her main event, but she hadn’t done it in a while. A few minutes before the meet, she told her mother that she would be doing a floor routine. “Really? Oh, shoot,” was what Maria thought. “She hasn’t done floor in a long time.” She hoped Sophina was healthy enough.

Then the music started, and the crowd fed off of her. “Boom, she went up there and did it it … and I saw it’s the same old Sophina,” Maria said. “Her real self came to life.”

But Sophina didn’t process it immediately, because she and her family were dancing all through the routine. So was the crowd. Two football players, Alex Van Dyke and Austin Roberts, felt it too. “I guess no one’s really danced that way before,” Roberts said. Van Dyke said he could “feel that change of energy in the stands.”

Though Sophina didn’t actually win the floor excercise, she scored a 9.925 to help UCLA come from behind to defeat Utah in the meeting of top 10 teams.

So how does a 15-year struggle crystallize into a 90-second viral hit?

On Saturday, someone named Marcus Cheatham shared footage of the meet on Facebook. The caption was simple: “She MURDERED it! Sophina DeJesus of UCLA, everybody.” By Sunday, it was all over the feeds of her teammates and their friends.

Her grandfather, who lives in Northern California, watched it from afar. “It went viral because it was perfect,” he said. She spent years practicing, he said, and after picking her own dance moves to her own music, she got to discover herself and show the world who she really was. “The key to why it was so great is, she was so happy inside.” It reflected her spirit, he said, and her heritage, the years of public service that went into her making. As a result, he said, “She’s just ... love itself.”

To her mom, “it was God’s miracle,” she said. Her father thought so, too, he said, before qualifying that he is not a “church-going man.”

The attention was new to Kondos Field, a veteran coach. “We’ve never had anyone blow up like this,” she said. The morning after the meet, she saw the view count go up to 3 million, then 10 million, and “it just grew from there.” Team members have seen coverage in their home newspapers in Britain; another said that a friend of a friend in Norway contacted her about her team. Puerto Rico’s El Nuevo Dia ran a story headlined “Sophina de Jesus podría representar a Puerto Rico” (Sophina DeJesus could represent Puerto Rico). In French, she’s “Sophina DeJesus, gymnaste anticonformiste.” The Irish Independent called her routine “stunning.”

By Wednesday, UCLA athletics spokeswoman Liza David had processed so many media requests she said she was living in the “Sophinaverse.”

***

It’s no secret that gymnastics is a sport dominated by white people. Since Sophina’s routine blew up, people have been calling her “unapologetically black,” or connecting with her because they feel she represents them. But asking just where Sophina’s success fits into this paradigm gets a little complicated.

UCLA gymnast Sophina DeJesus demonstrates how to perform one of her pop-culture inspired moves.

And her mom knows that. “If you’ve been in a sport that’s not known for being African American, there’s a story behind that,” she said. “Sometimes those stories can’t be out because she’s at her school, her teammates, and she’s got to keep it positive.”

Then she paused. “She’s been in a white sport for years, going back and forth,” she said. “You’ve got to ask yourself why. The answer is almost obvious. It’s not really our sport.”

Her father is a little more resigned to that reality. “It is what it is,” he said. “All we can let her do is let her be herself.”

And, as her grandfather sees it, it’s all about the gymnastics. Until it’s not. “When you talk to my granddaughter or Serena you find out they’ve been practicing their skills since they were babies,” he said. “Race doesn’t come in until it gets to be a public thing and people say, you’re the only one there. Then you have to stop and define yourself.”

Sophina says she hasn’t seen the pieces about her ethnicity. When people ask, she tells them that she’s half Puerto Rican, half black, and that she loves it. She revels in the diversity of her team. “It’s not mainly about one ethnicity doing this sport,” she says. “I do embrace my ethnicities for sure, and I hope to inspire others that are my ethnicity and aren’t and everyone in general, because we are all equal.”

***

Sophina might be a campus celebrity, but at the gym she’s a team member, and a girl who laughs a lot and breaks out into silly dances when the moment presents itself. On Wednesday, the first formal practice since the Saturday meet, the team prepared for its next competition, which is this Saturday in Pauley Pavilion, against Oregon State.

As Sophina practices her floor routine, the one that’s now famous, a friend watches and screams, “Yeah, Soph!” She tries it again, and asks an assistant coach if it’s better. “Yes, but you could still, just, lean to the left a little more.” She’s standing under a wall bedecked with the phrase, “Good is the enemy to great” in blue script.

She goes to the balance beam and practices twirling her body around a raised plank; her teammates cheer, and Kondos Field lifts two small weights as she watches. Chalk dust is everywhere. “Make it a masterpiece,” the coach says. Sophina gets back on the beam, twists her leg, then raises it above her head. She lands a little shakily, then stands perpendicular to the beam, and does a body roll. She gets back up, and dismounts with a flip, still wavering.

She gets up and starts again, and catches her breath. She twirls, dances, moves her arms as if she’s flying, raises a right leg, then flips off and lands shakily, again. A friend cheers and gives her a high 10, but she blows an exasperated raspberry. It wasn’t perfect.

When her teammate practices on the uneven parallel bars and sticks it, Sophina watches intently. She lifts herself up onto a bar and whoops in delight.

The Olympics are still calling. She still has her paperwork filed to represent Puerto Rico. But she might be ready to leave this world behind, “to move on and experience a life other than gymnastics,” she says. “My goal now is to do acting.” Her dream is to be in a movie.

So when she graduates from UCLA this May, she plans on sticking around, here in L.A., the city that surrounds her spotlight.

Staff writer Sonali Kohli contributed to this report.

You can reach Joy Resmovits on Twitter @Joy_Resmovits and by email at Joy.Resmovits@LATimes.com

ALSO

The best — and worst — thing about being a student of color

UC expands its recruiting efforts targeting black and Latino students

Watch UCLA gymnast Sophina DeJesus Whip, Nae Nae and Dab to victory

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.