Great Read: In Calexico, former LAPD official finds a police department in turmoil

- Share via

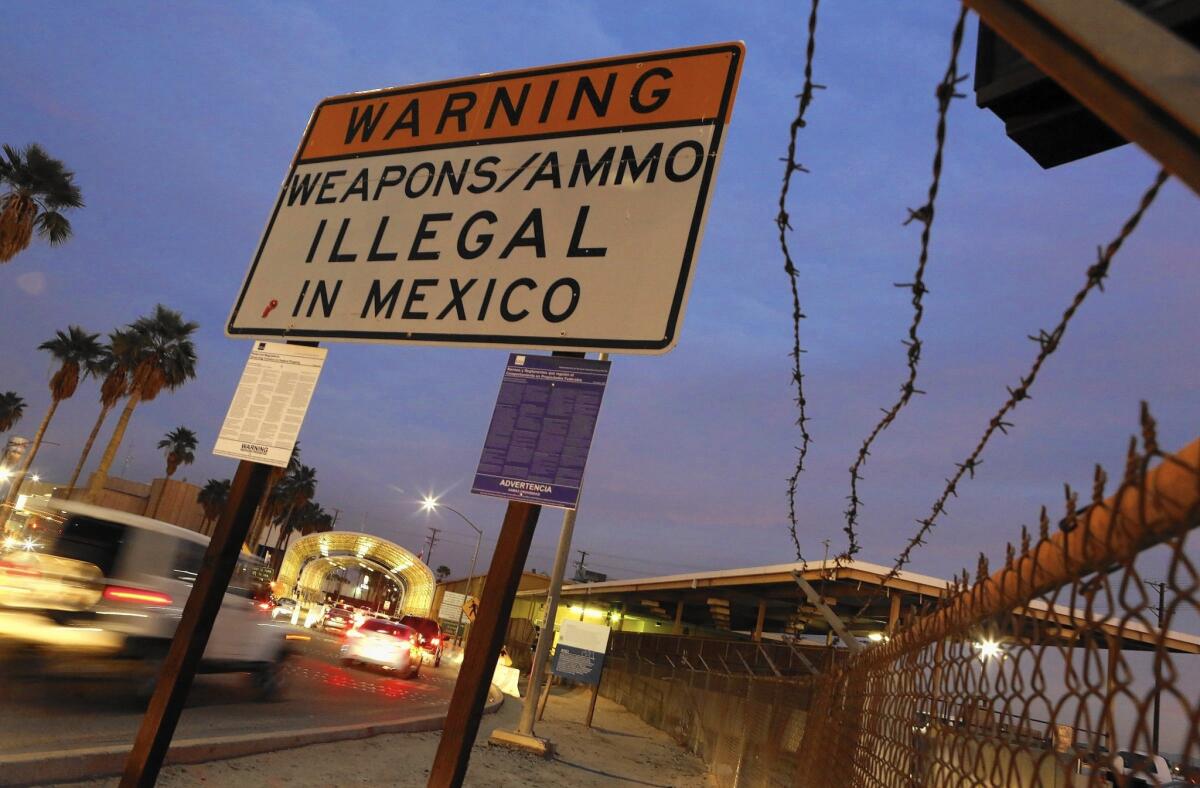

Reporting from CALEXICO, Calif. — Sitting hard up against a towering rusted fence that separates the United States from Mexico, this city is for most a dreary gantlet of fast-food restaurants and gas stations on the way to one of Calexico’s two official border crossings.

Calexico wasn’t a place that Mike Bostic had ever visited. In fact, the former high-ranking Los Angeles police official thought it was in Mexico until he got a call from its new city manager in September.

The call led to a secret meeting in a San Diego hotel room. There, the city manager, Richard Warne, told Bostic that a group of veteran cops was running the department like a fiefdom, taking home big overtime checks while very little police work was getting done.

Calexico needed a new police chief, Warne said. And he wanted Bostic for the job.

But after three decades in the Los Angeles Police Department, Bostic had been out of policing for years, trading his badge for the tailored suits of the corporate world. The healthy paychecks, along with a six-figure pension check each year from the LAPD, had left him, he said, “with more money than I could ever spend.”

SIGN UP for the free Great Reads newsletter >>

Sure, Bostic, 63, liked the idea of being a chief — he had been unceremoniously pushed aside at the end of his LAPD career and later made an unsuccessful bid to be chief of a quiet Orange County city.

But putting a police uniform back on had stopped being part of his plan long ago — never mind for a hard-on-its-luck border town of 40,000 where residents and elected officials say years of political infighting has created a revolving door for public servants, and where faith in the Police Department has dwindled.

------------

FOR THE RECORD

July 27, 7:20 p.m.: An earlier version of this article referred to California having two official border crossings. It is Calexico that has two official crossings; there are six in California.

------------

And yet Bostic is a man driven by his strong faith in two things: Christianity and himself. He couldn’t shake Warne’s offer.

“I just know that this is one of those things that God wanted me to do,” he said. “If you are a believer, you can’t ignore it.”

::

One afternoon in October, while Bostic waited in his car outside, Warne summoned the city’s chief into his office and promptly fired him. He then fetched Bostic, walked him into the town’s one police station and introduced him to a stunned group of officers.

That first day, Bostic asked a sergeant for a rundown of all the criminal and internal investigations the department had open. It was a short conversation. The sergeant told him there were no investigations, he said.

It was, Bostic said, a department that essentially had ceased to function. Dispatch records showed each of the about two dozen officers on the force had responded, on average, to only five radio calls for help in a month. Many officers, Bostic said, were months behind on writing crime reports.

Even the fact that Calexico’s crime rate appeared to be half that of a nearby city was not cause for encouragement. To Bostic, it was proof many residents had simply given up looking to the police for help and reporting crimes — a sentiment he said he heard repeatedly at town hall-style meetings.

“The community has been afraid even to call for too long,” said Eddie Guzman, 61, a mortgage broker who has lived in Calexico for more than 50 years. “I’m hoping that things will change under him. We need someone from the outside to come in and clean this place up.”

Guzman, like several other residents and city officials, chalked up the trouble in the Police Department — as well as the city government — to “the compadre system,” a set of unwritten but deeply ingrained rules that they say form the underpinnings for civic life in Calexico. Under the compadre system, they say, favors are traded like currency and personal relationships often trump the rule of law.

“The city has a long history of favoritism, cronyism and corruption among city officials,” Warne charged, noting he is the 26th city manager to be hired in the last 35 years. “The hiring of friends, relatives and mistresses has been a common practice — people who were clearly unqualified for their jobs. Goods and services are purchased based on personal connections without any consideration of quality.”

Three police officers whom Bostic fired, leaders in the union representing the city’s cops, object to his portrayal of a badly broken department. Instead, they argue, Bostic and Warne are part of a campaign by some City Council members to dismantle the union, which is a force in local politics and has battled reform-minded officials.

They acknowledge there were serious productivity issues in the department and few investigations done but blame it on inadequate staffing.

“Bostic is a scam artist. He’s led everybody to believe all these terrible things are going on,” one of the fired officers, Luis Casillas, said in an interview. “You have him and a city manager who say they need these outrageous salaries to clean up all this corruption … but really they see us as a political threat.”

::

Since arriving in Calexico, Bostic has unabashedly presented himself as a savior, promising residents he will rid their Police Department of “the cancer living within it” — a refrain during his first months on the job.

“These people are so desperate for help,” he said. “The LAPD has given me a unique set of skills and training that you can’t get many places.... I know exactly what to do to fix this place.”

Bostic hasn’t shied away from such grand statements, touting the major role he played in reforming the LAPD. Although he did have a hand in trying to push through changes that followed some of the LAPD’s worst episodes, the reality of his time there is more modest.

In the wake of the videotaped beating by officers of Rodney King, then-Chief Daryl Gates assigned Bostic to review the department’s use-of-force and training procedures. In his role, Bostic was critical of some problems he identified but wasn’t in a position to make significant changes himself.

Bostic testified as the government’s use-of-force expert during the state trial against the officers. Defense attorneys picked him apart on cross-examination, however, forcing him to admit he had formed his opinion of the beating after only a few viewings of the tape. After acquitting the officers, jurors said that they did not find Bostic credible.

He climbed the ranks to become an assistant chief, at times running the department when the chief was away. But after Bostic clashed with William Bratton, who was hired as chief in 2002, Bratton demoted him and exiled him from his inner circle.

::

Soon after he took over in Calexico, Bostic said he contacted the FBI, relaying concerns he had about some of his officers. Then, on a morning in late October, dozens of agents descended on the police station, seizing computer hard drives and documents.

FBI officials acknowledged the ongoing investigation but declined to comment on its scope or focus. Bostic, for his part, has refused to elaborate on the probe. But it seems to have struck a sensitive chord with him. Twice after the raid, Bostic choked back tears when answering reporters’ questions about the investigation.

“There could be nothing more embarrassing than to have your department under that kind of scrutiny.... It was literally the most disappointing day in all my years of policing,” he said at one news conference after composing himself.

The problems, Bostic said, stemmed from half a dozen or so officers, who also held sway in the police officers union. Bostic said they effectively ran the department, threatening other officers with misconduct investigations if they got out of line and running the department’s $450,000 annual budget for overtime to nearly $1.5 million.

“They believed they were untouchable. They still believe it, even since I’ve arrived. They’ve been protected for so long.”

::

Until earlier this year, Luis Casillas, German Duran and Frank Uriarte were department veterans and union leaders. Bostic fired the three men along with a few others.

Citing privacy laws, Bostic has declined to say why he booted them, but they said they had been wrongly accused of taking inflated overtime payments, among other allegations of misconduct.

Casillas said the overtime allegations were baseless, chalking up the confusion to honest mistakes. “Everyone worked the hours they worked,” he said. “We got fired for typos and technicalities in how the paperwork was filled out.”

In response to Bostic’s extortion claims, Casillas said: “No, never. None of us ever did that to any other officers. We never threatened anyone.”

The former cops and like-minded members of the City Council have railed against the $19,000-a-month pay Bostic is receiving on his month-to-month contract — the equivalent of a $225,000 $228,000 annual salary. (By comparison, when LAPD Chief Charlie Beck was reappointed to a second term last summer, his salary was $325,000 — for a force of nearly 10,000 officers.)

In a lawsuit filed this month in federal court, officers fired by Bostic accused him of being “a rogue police chief” driven by greed who framed the former cops.

Dramatic allegations aside, such a sizable salary for the chief of a small department in a poor city has raised eyebrows even among some supporters. Bostic insists he’s not in Calexico for the money, but he doesn’t apologize for the pay.

“You get what you pay for. He will cost more than previous chiefs, but it’s an investment that in the long run will be worth it,” Councilman John Moreno said. “Some people have been critical of this outsider coming here to help us. It’s not about being an insider or outsider. It’s about being qualified.”

So far, Bostic said, there hasn’t been much time to implement fixes because his time has been consumed by internal investigations into possible misconduct by officers.

When council members opposed to Bostic and Warne thwarted efforts to give the men the multiyear contracts they’ve demanded, the council received a stern letter from an organization that provides Calexico the insurance policy every city needs to protect itself against lawsuits and other liabilities. The group made clear it considered the men two bright spots in an otherwise dysfunctional city government and threatened to pull Calexico’s insurance coverage.

With the city facing collapse, one of the recalcitrant council members relented, agreeing last month to award Warne a contract. The vote cleared the way for Warne to negotiate a long-term deal with Bostic, who has said he needs two or three years to carry out his plans for remaking the department.

But in the hostile, tumultuous world of small-town politics in Calexico, there’s no telling whether Bostic will get the time he says he needs. Armando Real, the council member who reluctantly approved Warne’s deal, said he is determined to find a way to send Bostic packing.

It is, Moreno said with a resigned shake of his head, just business as usual in Calexico.

“Mike Bostic is here to fix our Police Department. I believe in him,” Moreno said. “It’ll take some time; he’s going to need to step on some toes. But it can be done, as long as we let him stay around long enough.”

MORE GREAT READS:

After poachers slaughter their mothers, baby rhinos find a home at South Africa orphanage

No room at the inn for innocence

India test cheating stirs outrage — then people start dying

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.