Fear and shock may play role in silence after woman’s beating death

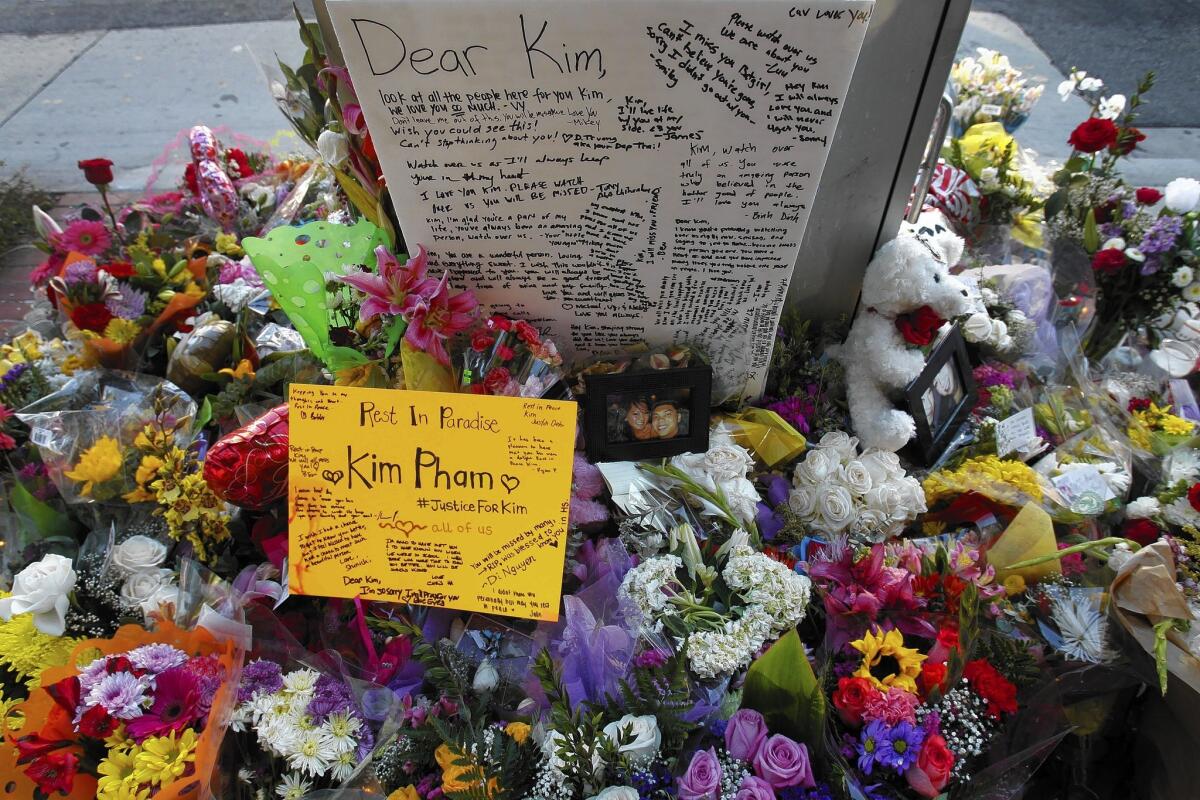

The beating death of Kim Pham has begun to morph into urban legend a la Kitty Genovese, the New York City woman stabbed to death 50 years ago while dozens of bystanders supposedly watched but did nothing to help her.

In the Genovese case, it took decades to debunk that claim, which became the basis of a psychological concept called the “bystander effect” that explains why crowds fail to come to a victim’s aid.

In the Pham case, it took about two weeks for an Orange County prosecutor to correct reports that bystanders did nothing to help as Pham was kicked and punched outside a nightclub in downtown Santa Ana.

As many as 15 witnesses may have tried to intervene in the brief fight, Senior Deputy Dist. Atty. Troy Pino said Thursday, at a court hearing for two young women charged with killing Pham.

That’s not what video clips of the melee suggest or what some witnesses have said. But the case has been troublingly murky from its outset.

The district attorney’s declaration may tidy up a public narrative that’s taken on a life of its own and blurred the line between villains and victims, painting Pham as the one who threw the first punch, her friends as obstacles to justice and the witnesses to her beating as callous observers who did nothing to stop the brawl.

Still, it won’t resolve the issue Pham’s death has raised — why some of the young people out with her refused to talk with police about what happened on that sidewalk the night their friend died.

And it won’t erase images we’ve already seen, of club-goers holding their cellphones aloft to record the sight of a woman being stomped.

::

I blamed a lack of empathy for both of those failures in my Tuesday column about Pham’s death.

Many readers emailed to say that was too harsh; they blamed fear instead.

“I’m afraid that people’s reluctance to intervene is heavily influenced these days by the belief that you’ll get shot if you do,” wrote Irving Lefberg. “Any of us can be found easily through social media and bumped off.”

Some took issue with my contention that anyone in the crowd who saw what happened has a responsibility to speak up.

“If your daughter was the one who knew the identity of the killers, would you demand she step forward?” asked Arthur O. Armstrong. “She may well make the world a better place, but she won’t be around to enjoy it.”

Others were incensed by accounts of the silence of Pham’s friends, who are part of a Vietnamese American community with a traditional distrust of police.

“I’m not interested in any more news about … how grief-stricken her family and friends are, if her friends refuse to cooperate with law enforcement in favor of a culture of silence brought here from Vietnam,” George Izaguirre said.

“They either choose to be good citizens or consign themselves to the margins of society.”

But Pino told me even that perception is overblown.

Many of Pham’s friends, he wrote in an email, were helpful from the start. “While not everyone has come yet forward, it was never the case that Ms. Pham’s companions refused to cooperate.”

::

Pino said he’s surprised that this case has become a national symbol of urban apathy.

Maybe we’re just desperate for some explanation of how a young woman can be beaten to death on a crowded sidewalk in plain sight.

At least the focus on bystanders in this case has led to discussions and soul-searching about how to handle violent encounters.

“Let’s be real, there’s no way you can peacefully break up a brawl,” wrote Maple Lee, whose lifeguard training teaches her to call 911 rather than wade into a fight.

“If I’m in downtown Santa Ana, having a good time with my friends, feeling tipsy/good, I WOULD NOT want to get involved in a scrum like that,” Lee wrote. “When tempers are flaring and you try to pull someone off your friend and they don’t budge ... How do you properly restrain a violent, possibly drunk person?”

Several readers admitted they’d witnessed beatings and failed to get involved. They were confused, afraid; they didn’t want to be that Good Samaritan who gets pummeled trying to stop a fight.

“I didn’t know the circumstances and I froze up,” wrote Paul Pena, recalling an incident many years ago when he witnessed an older man being roughed up by a young man. “I wish I had intervened but I didn’t. I think I would today.”

It is easy to imagine we’d know what to do, but reality’s more complicated.

Consider the scene John Batjiaka watched unfold in Santa Monica on the Third Street Promenade. Two women started shouting at each other. It escalated to hitting, kicking and pulling hair. A young man with them tried to stop them, but they just kept brawling.

Batjiaka realizes now, in retrospect, that either of those women could have been seriously hurt if her head had hit the sidewalk.

But his first reaction then “was one of total shock ... I was stupefied by it,” he wrote. “I’m sure everybody observing it would like to have done something, but perhaps they felt the same way I did.”

That might also be how people felt outside that Santa Ana nightclub, as insults and punches flew — before one young woman wound up dead and two were charged with murder.

Twitter: @SandyBanksLAT

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.