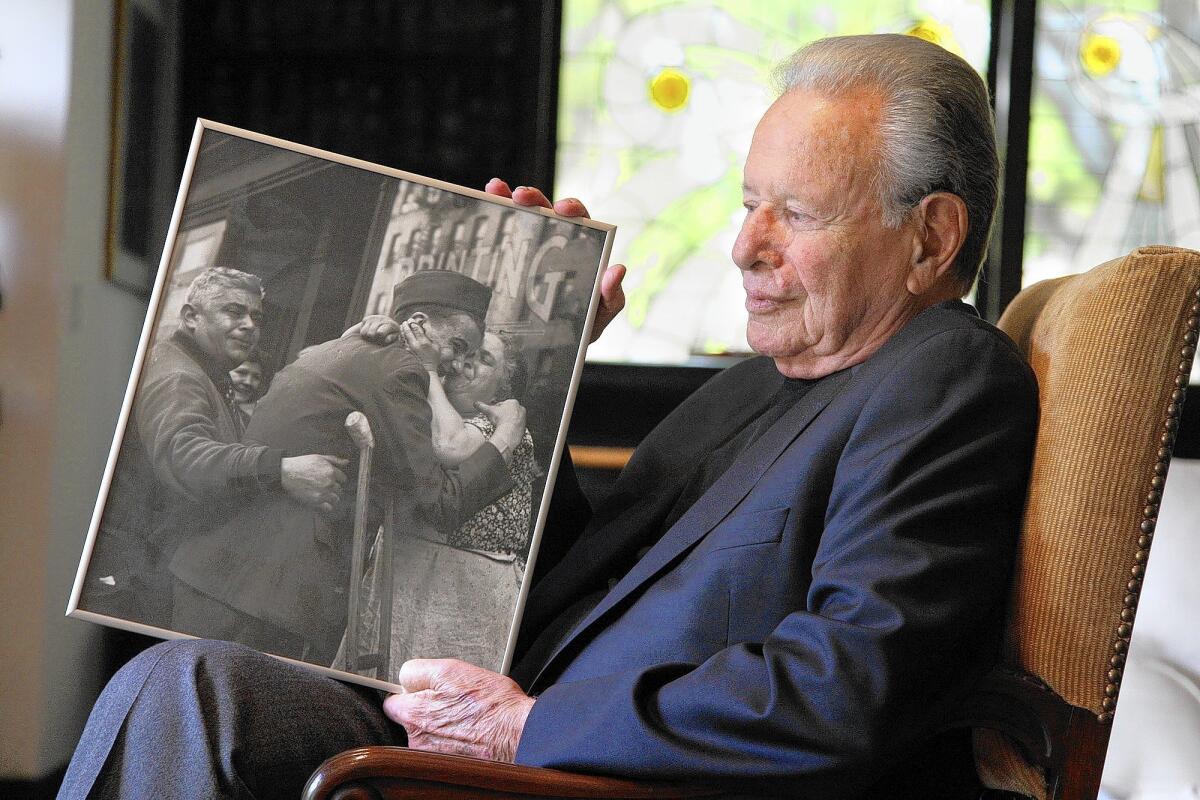

Film producer Mace Neufeld recalls his Pulitzer-listed photograph

- Share via

In time he would become a movie producer whose films included such hits as “The Hunt for Red October,” “Patriot Games” and “Invictus.”

But in 1944 Mace Neufeld was a 16-year-old high school senior who loved to take pictures, and thanks to a bit of luck — and hustle — he became a contender for the Pulitzer Prize in photography.

Neufeld recently recalled the experience. He was a senior at Stuyvesant High School in New York City, and one day in November 1944 he was on his way to work as a photographer for Mangels, a dress store. He was making 25 cents for each dress he photographed.

While walking on East 15th Street between 2nd and 3rd avenues, Neufeld noticed a taxi stop at a building across the street. He saw a soldier on crutches struggling to get out of the vehicle. A window opened in the building and someone shouted, “Sammy’s home!”

A man rushed out of the printing shop on the building’s ground floor. The man, Sammy’s father, embraced him. So did Sammy’s mother, who also gave her wounded son a kiss on the cheek.

Neufeld, who happened to be carrying his Kodak camera, ran into the middle of the street and, with no traffic coming, snapped one photo.

“I didn’t want to intrude on this emotional event,” he said, “but at the same time I knew I wanted the picture.”

Later that evening he went to his darkroom in his parents’ apartment and developed the film. It was the last frame on what was probably a 24-exposure roll. He thought the shot looked pretty good, and the next day he showed it to a friend who suggested he sell it to the newspapers.

The photo of a wounded soldier’s parents welcoming him home — a scene reminiscent of a Norman Rockwell painting — seemed to capture the emotions of a war-weary nation. Neufeld sold copies of the photo to the New York Daily News and International News Photos for $250 apiece.

The Daily News wanted the soldier’s name, so Neufeld returned to the apartment and learned that Sammy was Pvt. Sam Macchia, a 21-year-old New York native who had been wounded in both legs by a mortar shell in the battle for the town of Saint-Lo in northern France. He had been overseas for 17 months. Neufeld never saw him again.

Subsequently, the Daily News ran the photograph, on a full page, on the back cover of the Sunday rotogravure section. The New York World Telegram Sun printed the shot as “Picture of the Year.” Neufeld entered the picture into the first Eastman Kodak National High Salon of Photography and took the first prize of $100. He also got a call from a company in Chicago, which wanted to use the photo as a war poster.

He later found out his photo had been on the short list for the 1945 Pulitzer Prize.

As recounted in the book “The Pulitzer Prize Archive: Press Photography Awards, 1942-1998,” Neufeld’s photograph was a finalist for the Pulitzer in 1945. His photo was labeled “Warrior’s Return — a Wounded Veteran Greeting Family” by Morris Neufeld, as he was known then.

As it turned out, the Pulitzer judge gave the award to a photograph that, technically, didn’t qualify because it was not taken in the correct year. The award went to Joe Rosenthal for his iconic picture of Marines planting the American flag on Mt. Suribachi on Iwo Jima, Japan, even though it was shot in 1945. (The awards are handed out for work done the previous year.)

But as John Hohenberg wrote in “The Pulitzer Prizes,” the photo “swept aside” any technicalities in this instance. Rosenthal’s picture had dominated the front page of almost every American daily newspaper.

Neufeld’s photo may not have won the Pulitzer, but it was exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, part of a collection curated by Edward Steichen.

Neufeld got interested in photography when he was 10. His uncle, Joe Robbins, ran a drugstore in Yonkers that had a darkroom in the back, where he showed young Neufeld how to make a print. The boy was hooked and soon obtained his first camera. “I used my camera to take pictures of my cousins, friends, street scenes and anything I thought might be interesting,” Neufeld said.

His first job as a photographer was at the dress store, and he worked there until he graduated from high school. Later he was offered photography scholarships at the University of Ohio and USC.

“My parents didn’t want me to be a photographer and they said I had to go to college first, and if then I wanted to, I could do that,” he said.

Neufeld ended up enrolling at Yale because it was closer to home. He put his camera aside as his interest turned to motion pictures.

Neufeld, now 85, went on to produce a number of films based on books by Tom Clancy, including “Patriot Games” and “Clear and Present Danger.” He also produced “The Sum of All Fears,” “Bless the Child” and “The Omen.”

Neufeld became a collector of African and Oceanic paintings and sculptures, which are on display at his house in Beverly Hills. On one wall, in a modest frame, hangs his photo of Pvt. Macchia.

The photograph still brings Neufeld back to the moment he ran into the street to capture a family’s joy. It reminds him, he says, “that I probably would have been happier being a photographer than a movie producer.”

Times staff writer Steve Padilla contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.