New life for an old gem in Boyle Heights

On Cinco de Mayo in 1945, thousands of people gathered to dedicate the Casa del Mexicano, a community center that served as a sentinel of Mexican culture in Los Angeles.

In the 1950s, after the center moved west to Boyle Heights, stars from as far away as Spain flew to Los Angeles to perform. Wealthy Mexican bureaucrats, adorned with pearls and bow ties, mingled with celebrities who included Ricardo Montalban and Maria Felix. The events filled the center’s coffers with donations.

In the 1960s, a former President of Mexico, Miguel Aleman, put Casa del Mexicano at the top of his list of places to visit in Los Angeles. The building seemed a majestic anachronism tucked away in an unexpected cul-de-sac of a Mexican American barrio, its massive proportions and stately dome prompting double takes.

Then, about seven or eight years ago, Casa del Mexicano fell into disrepair. The roof leaked, windows were jammed shut and the structure reeked of vermin. Advisory committee members waged a nasty court fight to determine who would seize control of the Boyle Heights building and the organization that runs it.

Today, the historic center is slowly coming back to life.

The doors are open again and the center’s roster of programs -- sports, theater, English classes, beauty pageants and relief to the needy -- is growing. As part of a partial remodel of the 104-year-oldbuilding, the facade has been painted a vivid green and yellow, new floors have been installed and the dilapidated dome has been fixed. Soon the inside of that dome will feature an elaborate mural pairing Benito Juarez and Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla with George Washington and Abraham Lincoln.

The people now running Los Angeles’ first civic and cultural center that catered to Mexicans are working hard to recapture a prominent place in the Eastside’s social landscape. Among their greatest challenges: dealing with perceptions that the organization is too hyper-focused on Mexican immigrants and out of touch with new generations of Mexican Americans.

“The work that should have happened fell behind and now we have to follow up,” said Martha Soriano, president of the Comite de Beneficencia Mexicana Inc., the nonprofit organization that oversees the Casa del Mexicano. “We have to give pride to this organization after so many years.”

That goal won’t come easily. The center serves all ethnic groups, but down the street, even some neighbors don’t know what goes on inside.

Much of what goes on behind the lemon-yellow doors is about tradition.

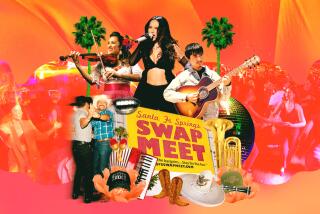

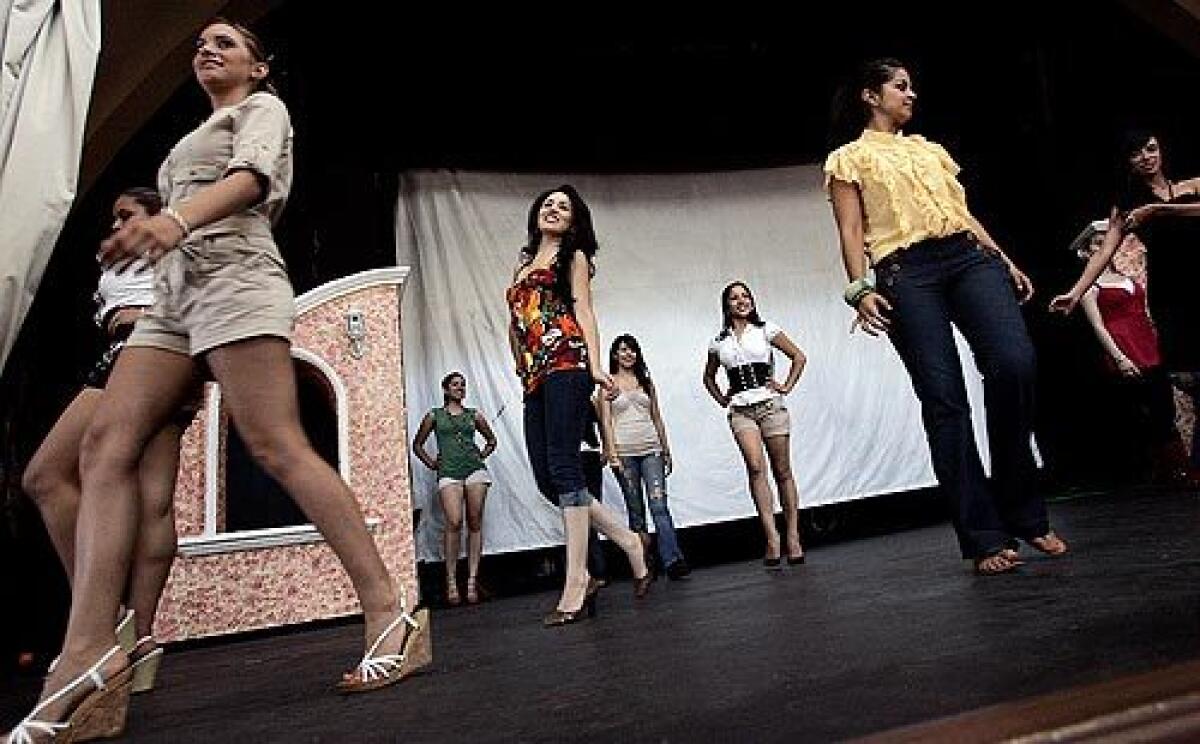

On a recent Sunday, for example, Marielena Bravo, 22, held her waist and swung her hips, parading onstage with 17 other contestants determined to take the Miss Jalisco-Los Angeles crown. A Mexican ranchera blared from a boombox in the corner as mothers rooted for their daughters and whispered about the competition.

Decades earlier, Bravo’s own mother strutted her charms on the same platform, taking part in a beauty pageant, a Casa del Mexicano ritual that dates back nearly 50 years.

The history of the structure that houses Casa del Mexicano is not complete.

A plaque says it was built in 1904 as the Euclid Heights Methodist Church. Some accounts say it eventually became a synagogue, catering to the neighborhood’s once-large Jewish community, but no complete record of its tenants can be found.

In 1931, a few miles from the Boyle Heights building, the Mexican Consulate established the Casa del Mexicano. The center’s mission was to promote Mexican pride at a time when thousands of Mexicans were being forced to return south, blamed for stealing jobs from Americans coping with the Great Depression.

The center offered educational programs, held Christmas gift drives, shipped the bodies of Mexican nationals to Mexico and donated money to disaster victims in Latin America. Nineteen years later it moved into the Boyle Heights building.

Thousands of visitors have cycled through 2900 Calle Pedro Infante, bearing lasting impressions.

City Councilman Jose Huizar, 39, who oversees Los Angeles’ 14th District, where Casa del Mexicano is now based, remembers the center for its literary offerings. The building was on his way home from school, and its few shelves holding a selection of travel and history books became his de facto neighborhood library.

“It was a place to spend my time and stay away from the streets, a self-created school program for kids,” Huizar said. The organization deserves praise for standing on its own, he said, but “the place needs to be taken to the next level” with more art programs and outreach to young people.

Yolanda Hernandez’s relationship with Casa del Mexicano goes back nearly 70 years. The 72-year-old woman, who lives a few blocks away, used to attend piano recitals there as a teenager.

For two years, she took Spanish classes and learned about Mexico’s history and geography.

“You’d walk in and see this very beautiful chandelier that would cast a light on all the stained-glass windows,” Hernandez said.

Eventually, she said, the place and its neighborhood became “too Mexican” for her, ignoring the needs of more assimilated Mexican Americans.

Balancing the needs of older and newer generations became a problem for Casa del Mexicano, according to Jerry Velasco, president of Nosotros, a nonprofit promoting the image of Latinos in the entertainment business. Casa del Mexicano accomplished a lot with little help, but it fell short in connecting with American Latinos, he said.

“There was a gap,” Velasco said.

“Casa del Mexicano did not relate to Chicanos, and Mexican Americans did not relate to the Casa del Mexicano philosophy,” he said.

Starting in the late 1990s, turmoil resulted as Casa del Mexicano’s leadership switched hands at least four times. Complaints of loud music late at night, trash and drugs became rampant. One president was ousted by his advisory committee in a series of lawsuits sprinkled with allegations of hostile encounters, armed guards and money mismanagement.

Martha Soriano eventually stepped in as president; her husband, Ruben, is the treasurer.

The couple, who work a series of jobs (Ruben installs car windshields and Martha runs a weekend catering business and sells makeup and health products) run the place as volunteers.

The Sorianos’ work has been praised by those who are delighted to see the Casa del Mexicano coming back to life and criticized by those who say they don’t have the community’s best interests at heart.

Martha Soriano brought in business owners to make up today’s new advisory 40-member committee. Many of the programs offered in the 1990s have returned.

Like previous leaders, she shies away from grants and public dollars because she does not want any conditions attached to donations.

Velasco, who tried to build connections between Casa del Mexicano and Mexican American groups 20 years ago, said he would like to see the community reach out and aid the 77-year-old organization.

The site is shabby, he said, “But as soon as you make that turn and see it, you think ‘Oh my God. What is this?’ You get this Mexican feeling, like you’re walking back in time to Mexico.”

esmeralda.bermudez

@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.