A turning point for Leimert Park Village

- Share via

At the Sunday drum circle at Leimert Park, the hypnotic beat of African drums breathes life into the neighborhood. Artists showcase their work. Vendors hawk clothes, soap and incense.

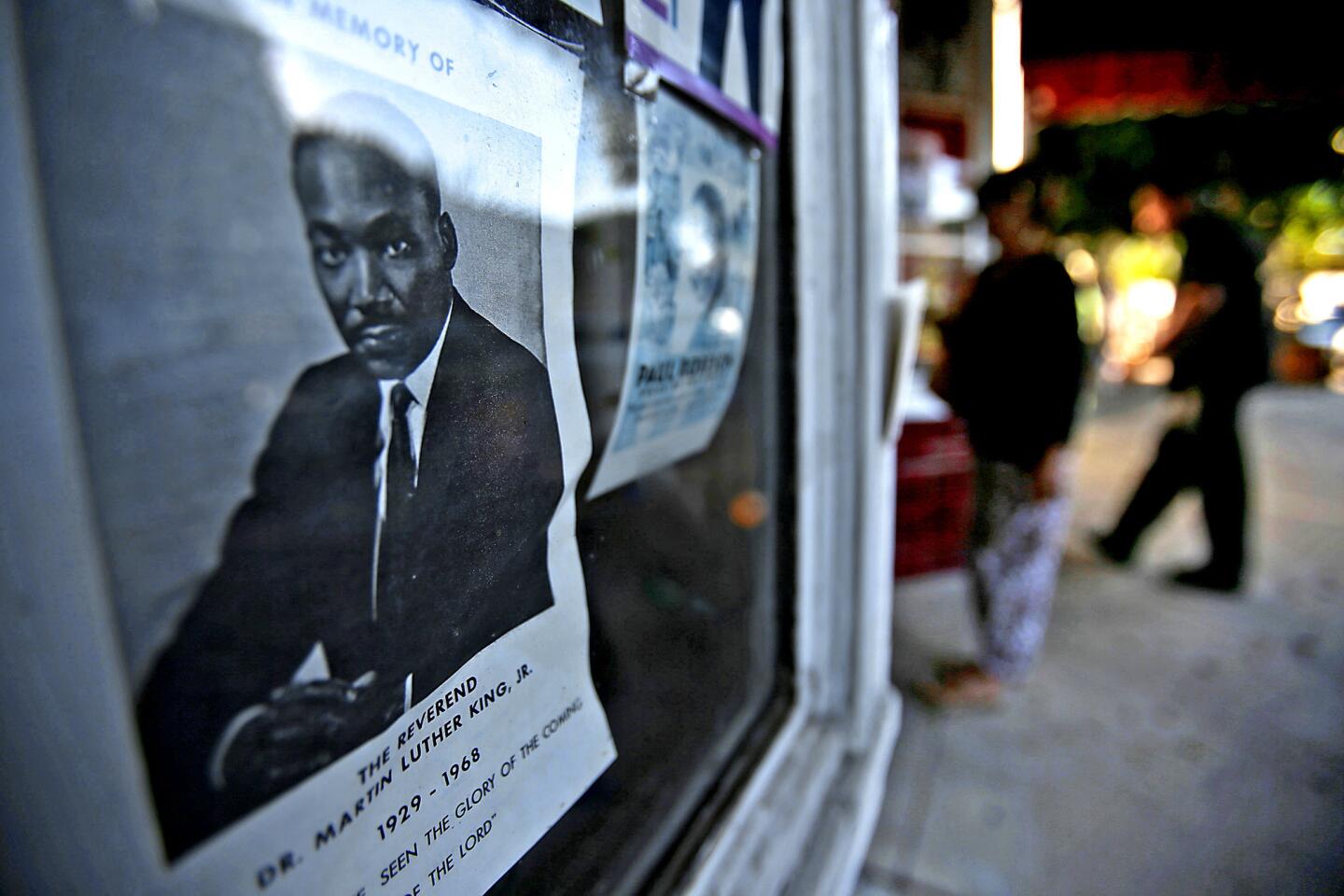

It almost feels like nothing has changed in the 20 years since this was the vibrant heart of the African American arts and culture scene in Los Angeles.

On other days, though, Leimert Park Village is a ghost town of broken windows and vacant storefronts.

In its heyday, the neighborhood was something of a West Coast Harlem dotted with jazz cafes, performance spaces and art galleries, and it was the community’s gathering spot after the 1992 riots.

FOR THE RECORD:

Leimert Park Village: In the Feb. 10 Section A, an article about a possible revitalization of Leimert Park Village with the addition of a planned light rail station said that the neighborhood’s Vision Theater had been closed for years. The theater is available to rent for special events.

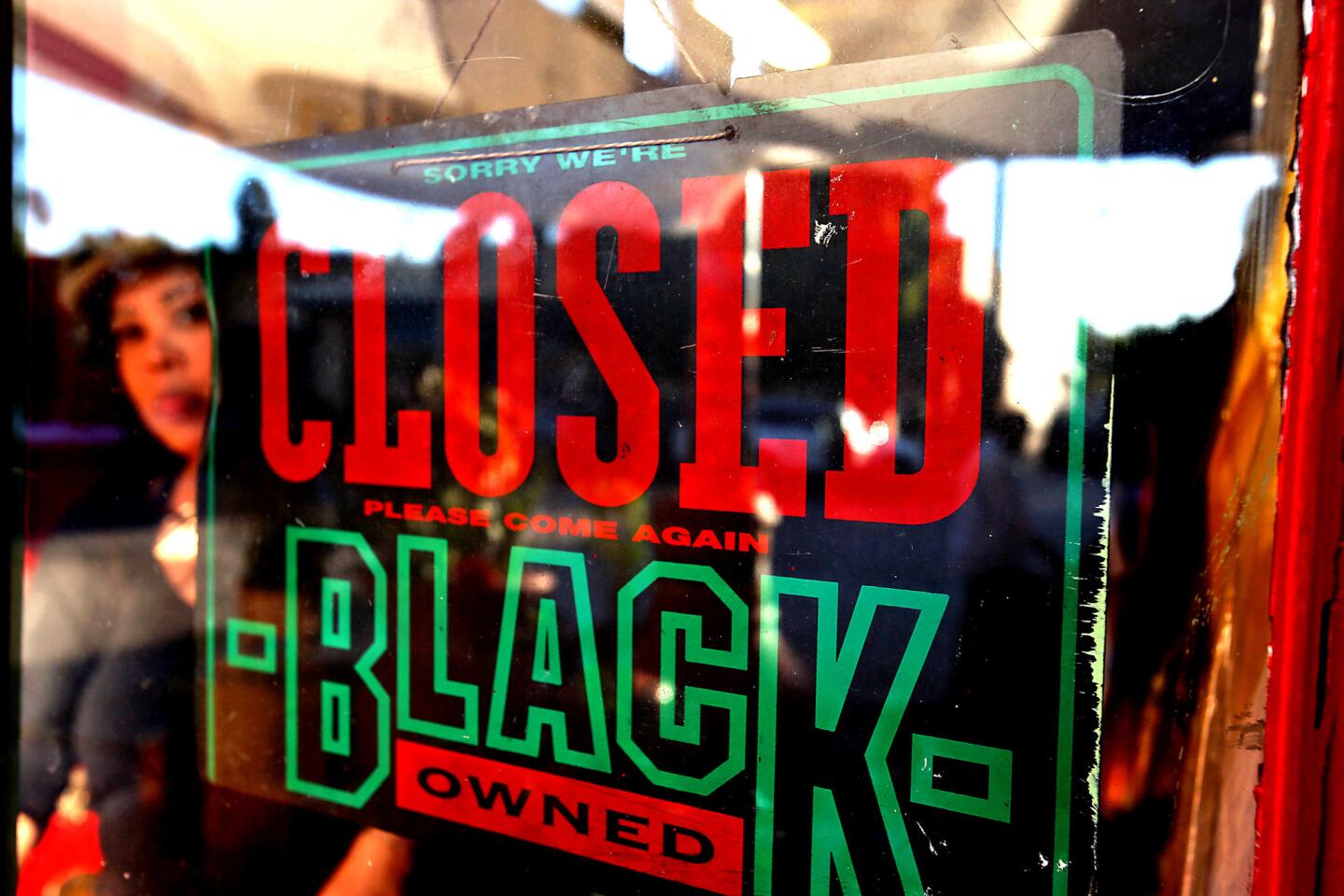

Efforts to revitalize the area by trying to attract chain stores and shopping center developments have been rejected by residents, saying they would prefer to restore it as a center of African American arts and culture.

That is particularly important, some South Los Angeles leaders say, because other once-prominent black neighborhoods now have Latino majorities: Central Avenue, once the center of the black jazz scene, and Watts.

“All the neighborhoods in South L.A. have changed except one: the Leimert Park area,” said Earl Ofari Hutchinson, president of the Los Angeles Urban Policy Roundtable. “It is the last vestige of not only a predominantly populated African American community, but also a predominantly business-centered African American community.”

The debate over Leimert’s future is coming to a head. South L.A. officials successfully fought last year to add a Leimert Park stop for the new Crenshaw/LAX light rail line, which is set to open in 2019.

For residents, the big question is whether the trains can bring back some of the village’s old luster and whether the mom-and-pop shops will be driven out in the process.

“Why can’t we have street vendors and a fine arts gallery here?” local artist Mira Gandy said. “You don’t have to lose its flavor. People have to be open.”

::

Leimert Park has long been associated with the elites of black Los Angeles.

Blacks began moving into the area in the 1950s, after the Supreme Court lifted racially restrictive covenants that barred non-white homeowners. The early arrivals — including former Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley — had to employ white intermediaries to buy homes in the exclusive neighborhood, Hutchinson said.

In those days, the village was considered something of a Beverly Hills for blacks. Designed by stepbrothers John and Frederick Olmsted, whose father was co-designer of New York’s Central Park, Leimert Park was designed as a quaint village of shops and homes surrounding a town square. As well-heeled African Americans moved in, white residents and businesses moved out.

Eventually, artists settled into the empty storefronts in a triangle-shaped shopping district split by Degnan Boulevard known as Leimert Park Village. A dozen or so small businesses that sold African artifacts and art opened.

By the 1970s, up-and-coming African American artists flocked to the area to set up studios and show their works at Brockman Gallery.

“In those buildings were once very powerful people,” said Ben Caldwell, who was an intern at the gallery when it nurtured black artists such as David Hammons and Elizabeth Catlett.

During the day, visitors sat outside popular jazz coffeehouse 5th Street Dick’s playing chess and writing poetry. At night, the jam sessions went into the wee hours at Caldwell’s Kaos Network and the World Stage.

But by the late 1990s, the village was in decline. Some middle-class blacks moved out of the area, and those remaining were increasingly doing their shopping elsewhere.

“They were now conditioned to think, ‘Ah. I can go to the Beverly Center and South Bay. Why do I need to go to Leimert Park? There is nothing there for me,’” said Hutchinson, who has lived in Leimert Park for more than half a century. “That was the first seed of decline.”

The Vision Theater, which brought popular acts into the Art Deco space, has been closed for years. Fifth Street Dick’s closed after the owner died. And a long-standing African American institution, Museum in Black, was evicted from its storefront.

In 2003, entrepreneur and TV personality Tavis Smiley proposed building a $4.5-million multimedia studio that would serve as an anchor for revitalization. The project included retail space, office rentals, a bookstore and rooftop restaurant. Residents opposed it, and the project eventually died.

A second project, a 500-unit apartment complex, was proposed a few years later. This time, residents organized a more formal opposition campaign. They petitioned city officials, posted “Save Leimert” signs throughout the neighborhood, and held educational workshops to “acquire the language to be able to speak intelligently” about redevelopment, said Lark Galloway-Gilliam, who spearheaded the campaign.

That project faltered too, and the village continued to decline.

In recent years, residents have held a series of community forums to discuss how to revive the village with a focus on arts and culture.

Community leaders say the key to improving the village is luring more residents from nearby affluent African American communities such as Baldwin Hills, View Park and Windsor Hills. The big question is what kind of businesses would draw those residents.

“Why is it ... you have so many small black businesses with a huge market that’s literally a stone throw from residential areas are struggling?” Hutchinson said.

There was excitement when a $10-million restoration of the Vision Theater was announced a few years ago. But the renovations of one of L.A.’s last remaining Art Deco theaters have dragged on and an additional $8 million is needed to finish the project. Cultural events such as a monthly art walk and plays held at Barbara Morrison Performing Arts Center occasionally draw patrons to the village, but business owners and officials said it’s not enough.

Councilman Bernard C. Parks said the key is to find a mix of businesses that would attract shoppers to the village more frequently.

“If you don’t bring anything that makes African Americans come then you just have buildings,” he said.

The coming light rail station might bring opportunities but also some potential pitfalls.

Members of the village’s business improvement district have started studying other light-rail stations around L.A. to see what kinds of developments are possible.

Caldwell and another artist also plan to open an art gallery there this year.

But there are signs that outside developers are also eyeing the village.

Two properties in the village were recently purchased by developers, one for $1.25 million and the other for $875,000. It’s unclear what the owners’ plans are, but residents are waiting anxiously for word.

With the rail line coming, residents say it’s inevitable that the village is going to change. But they hope the cultural history won’t be lost.

Samantha Walker sat on the edge of the water fountain on a recent Sunday listening to the drum circle. She still remembers a more lively scene years ago, when she would listen to jazz musicians jam until 2 a.m. and eat at the restaurants.

“All other cultures have a cultural center,” she said, noting Koreatown, Chinatown and Little Tokyo. “This is the only pure thing we have left. And we like it this way.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.