Must Reads: Thieves stole architectural gems from USC in a heist that remained hidden for years

- Share via

The thieves seemed to know exactly what they were looking for.

They entered an unmarked warehouse on a South Los Angeles side street, moved through a warren of file cabinets, yellowing papers and jettisoned desks, and breached a small storage room.

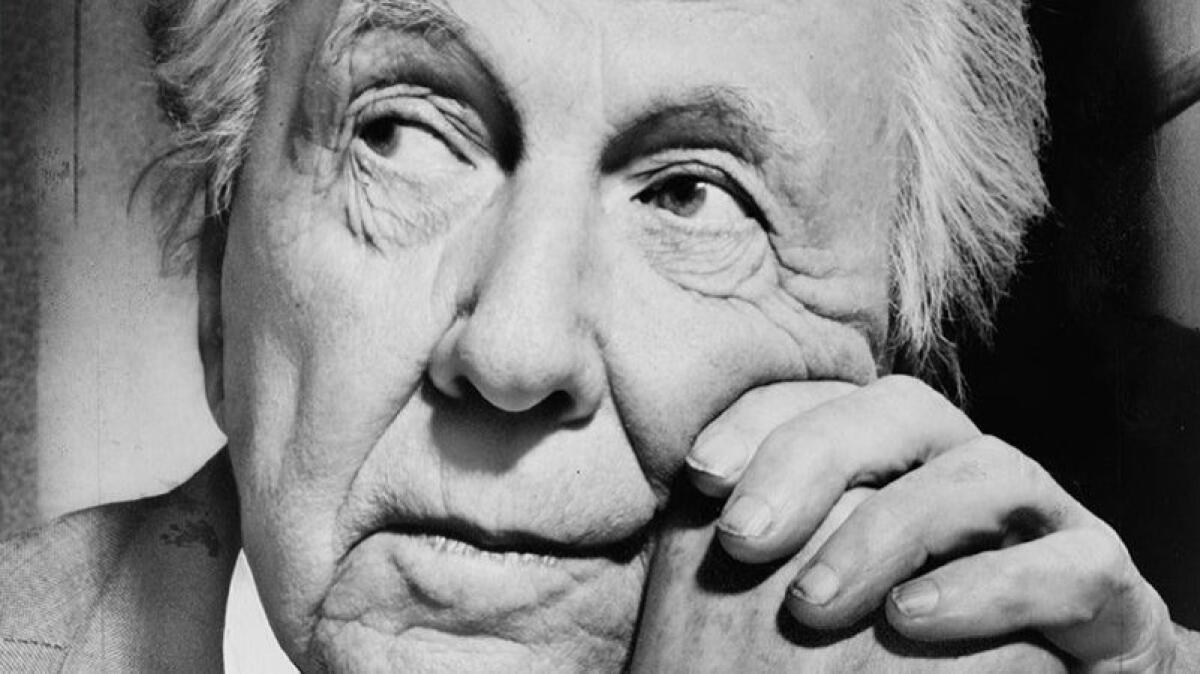

Inside was a cache of furniture designed by two of the most celebrated American architects of the 20th century, Frank Lloyd Wright and Rudolph Schindler.

The thieves made off with two of Wright’s striking floor lamps and a cushioned chair believed to have been designed by Schindler — a haul with a potential value of hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Six years after the heist at the USC warehouse, the identities of the perpetrators remain a mystery.

There is a second puzzle: Why didn’t the university report the theft to police at the time or seek the public’s help in recovering the irreplaceable pieces?

Detectives only learned of the larceny in recent weeks, after an anonymous letter to the Los Angeles Times revealed the crime.

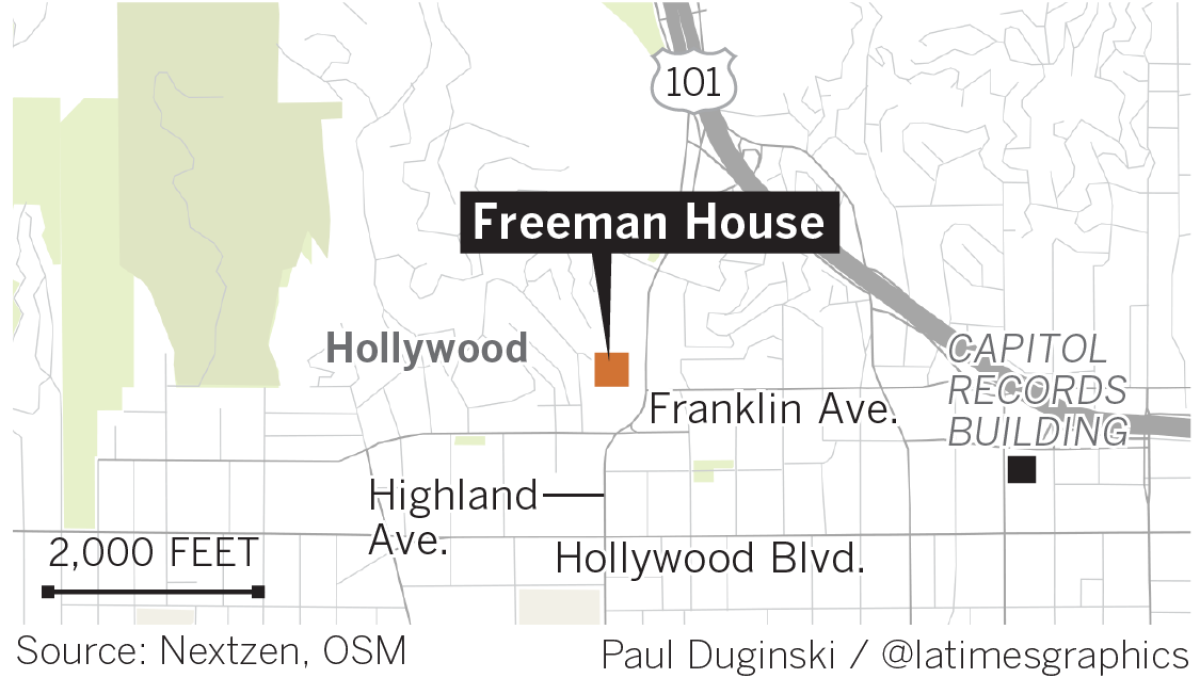

Ninety years ago, the lamps illuminated one of the most breathtaking living rooms in L.A. The residence belonged to Samuel Freeman and his dancer wife, Harriet, an avant-garde couple who had commissioned Wright to turn a steep and narrow plot in the Hollywood Hills into a showplace.

The architect, already famous and enjoying a midlife sojourn in California, ringed the living room with tall windows that provided dramatic views down Highland Avenue and of the surrounding hills.

The furniture he fashioned for the room included the 6-foot-high cast iron and glass lamps. His protege, Schindler, later worked on the house, adding his own unique furnishings.

For decades, the Freemans’ eclectic crowd of artists, scientists and leftists savored the home and its decor. “Casablanca” actor Claude Rains was a regular at the couple’s so-called salons, and Harriet Freeman feted legendary choreographer Martha Graham at a dinner party in the living room.

Samuel Freeman died in the living room in 1981. Harriet suffered a stroke and spent her final months in a bed in the living room. She died in 1986. Childless, they left the home and furniture to USC, hoping the university would treasure the property as a site for meetings, classes and historic preservation.

Preservationists quickly learned that maintaining the Freemans’ home, like other Wright designs in L.A., would be a major challenge. The residence’s hallmark — patterned cement-block walls that recalled Mayan temples — proved uniquely unsuited for California’s seismic environment.

The Freeman House suffered severe structural damage in the 1994 Northridge earthquake. Tiles tumbled from the house and broke. It took the university years to secure more than $1 million in restoration funding from the Federal Emergency Management Agency and other sources.

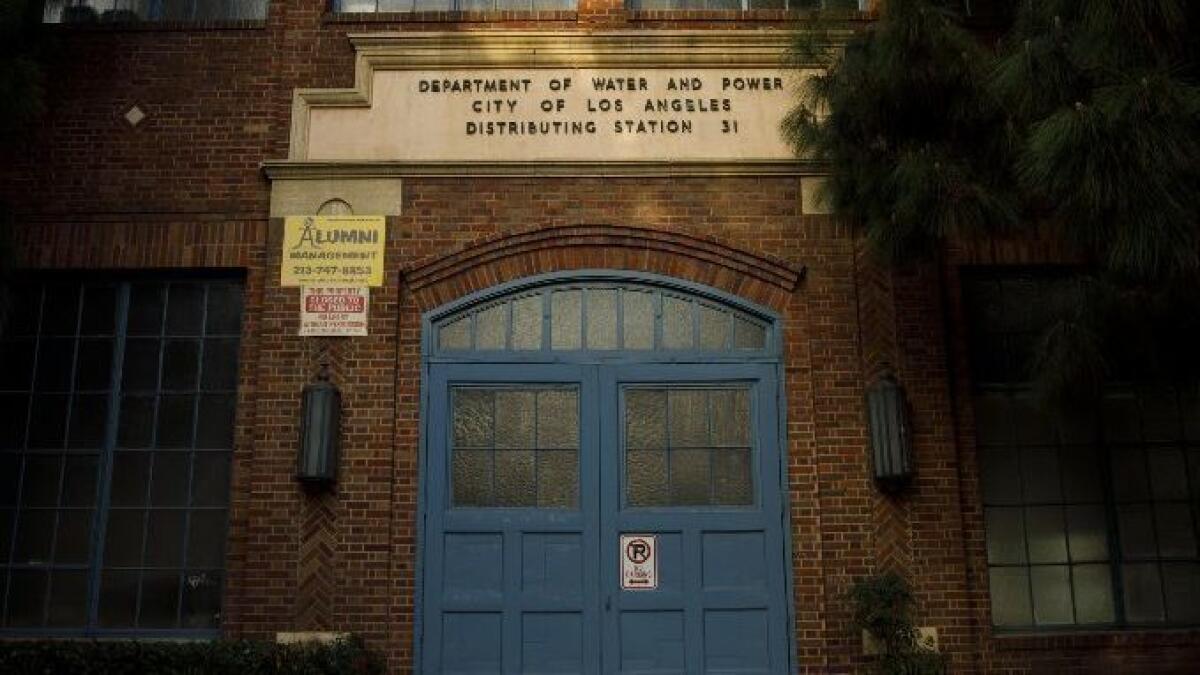

Around 2000, in advance of the work, USC moved the contents of the home, including the Wright and Schindler furniture, to the architecture school’s rented warehouse. The brick facility on 24th Street, formerly a city power station, has a cavernous interior with at least one separate, locked room.

Some broken tiles were stored in the main room while the furniture was placed in the locked area, according to people familiar with the warehouse. For the next decade, the pieces that had delighted the Freemans and their guests would sit in the dark, glimpsed only occasionally by USC faculty, staff and students.

A facilities staffer visiting the warehouse in September 2012 noticed items missing from the locked room.

There was no sign of a break-in or vandalism, and nothing but the Wright and Schindler furniture seemed to have been taken.

Kenneth Breisch, an associate professor who oversaw the graduate program in historic preservation, said that as far as he knew, there was only one key to the room and it was maintained by the facilities department.

The staffer who had discovered the missing items contacted Breisch to see whether he knew anything. Told no, the staffer said he planned to alert campus police, according to Breisch.

“I just assumed they were taking care of it,” said Breisch, who declined to name the staffer. “I just assumed, I think, that it probably didn’t consist of anything of value, [otherwise] I would have heard more.”

In fact, the stolen floor lamps and chair had significant value. The lamps are particularly rare and coveted by collectors. A nearly identical piece Wright made in the same period for a Hollywood Boulevard residence sold at auction two years ago for $100,000.

Told of the lamps’ theft recently, architect and author Thomas A. Heinz, the foremost expert in Wright’s interiors, exclaimed, “Wow. Wow.”

“Because these are so rare, I would say it’s a tremendous loss,” said Heinz, adding that Wright created about a dozen such lamps.

Schindler’s chairs are also in demand. Last July, two of the architect’s redwood “sling” chairs were reported stolen from an Olympic Boulevard storage unit rented by the Friends of the Schindler House, the nonprofit that maintains the architect’s former West Hollywood residence.

Board member Robert Sweeney told the police the chairs were original to the Kings Road landmark and estimated their value at $25,000 each.

Despite the clear value of the items taken, no one at USC filed a report with campus police, LAPD or the university’s insurance carriers. Word of the theft circulated among some at the architecture school, but few, if any, outsiders were told.

It remained a secret until last summer when someone’s conscience appeared to have been prodded by a listing at a Chicago auction. The listing described the lot for sale as a “textile block from the Samuel Freeman House, Los Angeles” and identified the seller as a private collector in Chicago. It was a 16-inch square, the size of the original Freeman blocks, and had discolorations indicating decades in the elements. It sold for $5,000 in June.

Weeks after its sale, The Times received an anonymous email describing the warehouse theft. The author also included a link to the auction and wrote that even if the sale was not connected to the theft, it was troubling. How could the tile have fallen into private hands when its ownership had passed directly from the Freemans to USC, the writer asked.

The Times approached USC about the alleged theft in mid-January. A university spokeswoman expressed skepticism, saying that even the most minor infractions are documented by the campus police and shared with administrators. It strained credulity, she said, that a suspected felony involving priceless works of art had gone unreported.

A search of campus police databases and inquiries to half a dozen employees turned up nothing about a theft, she said. But further investigation by USC’s Office of Professionalism and Ethics, a new unit set up after recent scandals, determined that the tip had merit.

On Jan. 22, campus police filed a report with the LAPD, identifying the three missing items. The university blamed the 6½-year delay in contacting authorities on a miscommunication between employees, according to police.

“It’s quite alarming, frankly, that there’s a gap,” said Lt. Perry Griffith of the Los Angeles Police Department’s Southwest station, who reviewed the report before handing it off to the department’s Art Theft Detail.

In a statement, USC said it was fully cooperating with the police probe and pursuing its own internal investigation.

“The university is reviewing its procedures and security measures related to the Freeman House and its assets,” the spokeswoman said in a statement. She added that the university “is working with its risk management team on the insurance claim process.”

LAPD Det. Don Hrycyk of the art theft unit said his investigation was at the preliminary stage.

“There was no forced entry, so it looks like someone who had access to a key,” Hrycyk said.

USC declined to identify those with access to the room and said in a statement, “It appears unlikely that there was only one key, however we expect that to be part of the investigation.”

The passage of time had made dusting for fingerprints and other forensic techniques all but impossible. Memories have faded, and witnesses are out of reach.

“A lot of these people are no longer at USC,” Hrycyk said.

The tile auctioned in Chicago is not part of the LAPD investigation, he said. USC said it had “no verification” as to whether it was stolen from the house.

Jeffrey Chusid, a Cornell University professor who is a leading authority on the Freeman House, said the auctioned tile appeared to be an original. Chusid, who lived in the house when he taught at USC in the 1980s and 1990s, said it was unlikely to be one that fell from the home during the earthquake because those were largely broken. During the 1990s, a vandal pried a tile from the street-side of the house, he said, “and that might be floating around.”

Richard Wright, the president of the Chicago auction house, said the seller told him he obtained the piece several years ago from a dealer. Wright said he believed that the tile was originally from the Freeman House’s garage and that it was removed after the 1994 earthquake.

“It’s my understanding that there was some restoration done to the house,” Wright said. “Given the not-great condition, it had been a tile that had been replaced.”

Wright said the collector who consigned the tile had attested to the legal title of the concrete block. Still, he said that in the world of art auctions, “it is not always perfectly clear how things get out.”

USC students training in historic preservation regularly visit the Freeman House, but it is not open to the public.

It is situated on a narrow, winding street that dead ends on a cliff side and has little parking. To the rare visitor, the home’s disrepair is obvious, with splintered wooden beams, peeling paint and gaps in the cement-tiled walls.

USC said it is examining “options to ensure there’s a promising future for the Freeman House.”

“It’s always been hard to make it a priority of the university,” Chusid said. “It’s just unfortunate.”

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.