City Beat: Would you donate a kidney to save your co-worker? What happens when near-strangers connect

Binh Nguyen’s doctor told him “his kidney was not compatible with life.” After enduring four years of dialysis and failing health, Nguyen was floored when a co-worker offered him a kidney.

- Share via

Think of all the people we know but do not know, the neighbors and co-workers we see but don’t see every day.

Sure, maybe we nod or wave. Maybe we even have a surface chat. How about this May gray or those Dodgers, that boss of ours, that abandoned couch down the street.

But what if one of these people was hurting or staying up night after night scared — about growing debt, say, or a frightening health prognosis? Would we sense that something was wrong? Would we ask? Would we see enough to notice if one of them was flickering out in plain sight?

And if we discovered that something terrible was happening to someone we did not know well, would we leap across the void that divides us to try to do something to help?

These are the questions that have been gnawing away at me in the last week, as I have witnessed just such a leap — on a very grand, very brave scale. Watching what Keith Michaelis has done for his co-worker Binh Nguyen has made me cringe at so many far smaller life moments when someone in my wide world needed help and I didn’t do a thing or didn’t do enough or maybe didn’t even notice.

Nguyen and Michaelis, who are both 44, work for the Walt Disney Co. in Glendale, in an office that creates video games based on Disney movies. Once they were on the same team and inhabited the same cluster of cubicles. Now they are separated by a hallway, perhaps 25 yards apart.

They haven’t been to one another’s homes. They do not socialize outside the office. Their wives met each other just last Friday — in a hospital lobby at Cedars-Sinai, while the two men simultaneously were undergoing major surgery. They wrapped their arms around each other and held tight.

That hug witnessed, let’s shed the formalities from here on in — because theirs is an intimate story.

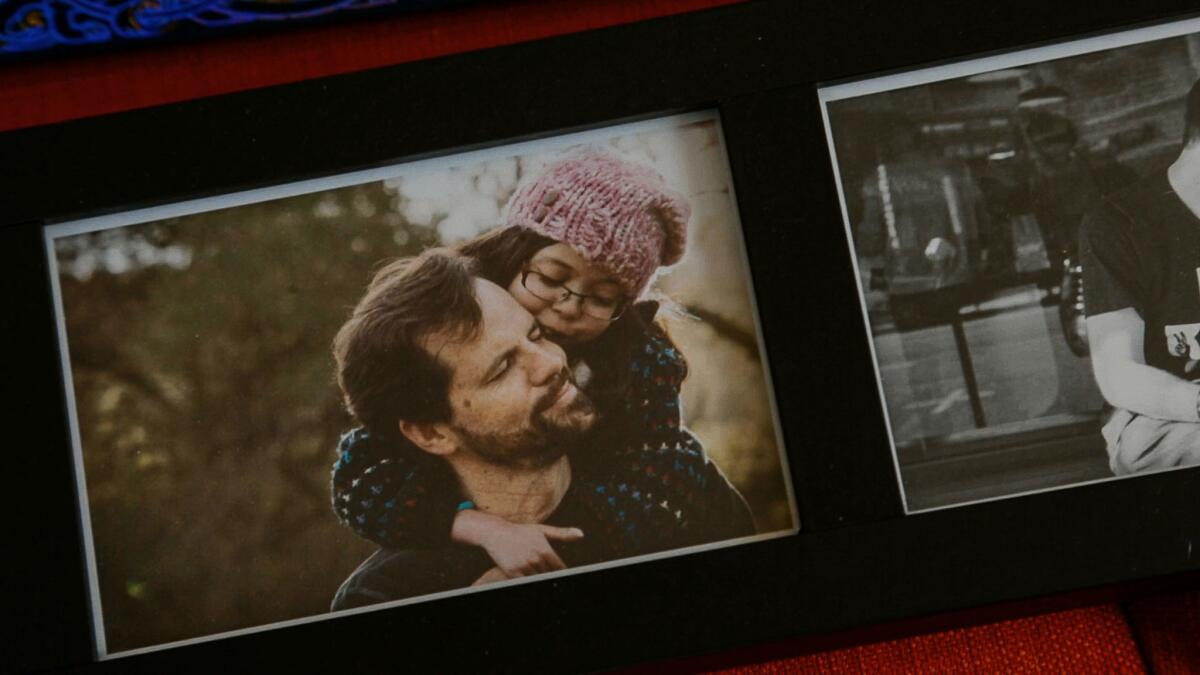

Binh is married to Karen (Morberg-Nguyen), Keith to Cecile — they are high school sweethearts. Both couples have young children.

Keith just stepped up to try to save Binh’s life.

Binh desperately needed a kidney. Keith had two — or, as he saw it, one to spare. He arrived at the hospital for the transplant surgery Friday morning radiating joy — as if his own heart were a plump cartoon version pinned onto his black down jacket — and said, “Let’s do this! Let’s get this thing done!”

Now a part of Keith is a part of Binh, and the two couples expect to be connected for life.

Binh hasn’t always felt such connections.

His life took a bad turn four years ago, after he kept getting sick and then not quite getting well. He had diabetes but he worked to control it with diet and exercise. He tended to shy away from doctors.

Then his body began hurting so badly that he started sitting up to sleep at night, and Karen, who is trained as a nurse, convinced him to go to the ER.

Tests were ordered. A doctor looked at them and said, unforgettably: “Your lab results are not compatible with life.”

CITY BEAT: The streets of L.A. can seem scary, but we need to separate fact from fear »

Binh’s kidneys had failed. He started dialysis — first in a clinic, then all night, every night, for 11 hours straight, tethered to a device the size of a laser printer, at home.

But dialysis is not a long-term solution. And Binh felt his strength ebbing away.

His son, Garret, who is now 9, had been 5 when Binh went to the ER. A couple of years later, Garret had turned to Binh and asked, “Hey, Dad, can you promise that you will be alive when I grow up?”

“It broke my heart that I couldn’t say yes,” Binh said, on the eve of the operation that might finally let him.

Binh isn’t very close to his family, who brought him as a baby to the U.S. from Saigon. His parents worked long hours. He was a latchkey kid. Outside of his wife and child, he has no experience of a tight family embrace.

In recent years, too, as he’s gotten weaker, he’s noticed close friends fade away. He recently sent some of them a letter, mostly to vent his hurt. He wanted them to know how it felt to be “drowning,” “sinking deeper and deeper,” without them reaching out to help.

“If you feel uncomfortable talking about it, I can understand that,” he wrote. “What I can’t understand is that you can’t get over that long enough to take one iota of a step towards something that resembles compassion.”

All of which made it hard for him to comprehend at first why Keith was willing to give him so much.

In the United States, nearly 95,000 people currently are on the kidney waiting list, according to the United Network for Organ Sharing, or UNOS, the nation’s organ transplant system. So far this year, 1,009 people have died waiting for kidneys.

Binh had been told that in the Los Angeles region he could expect a wait of eight to 10 years, which he knew he might not survive.

His family has been living in temporary apartments ever since he accidentally started a kitchen fire in their home trying to fry Karen’s favorite Indian food — puri — on her birthday in January 2018. He was very down and almost always nauseous, taking about 30 pills a day. His hopes and his dreams felt long gone.

Then came Keith, one of about 1,225 living kidney donors so far this year who is neither a spouse nor life partner of the recipient.

You might think that a person who would decide to give up a kidney to a co-worker would come from a place of great security and well-being — of look how much I have, look how good I have it, surely I can afford to give something up.

Keith’s generosity is different. It is shaped in part by a profound knowledge of loss and grief, and a desire to shield others from their ravages.

Fifteen years ago, Keith and Cecile had their first child, named Noah because they couldn’t find a girl’s name they liked, with the middle name Bella for balance.

Noah was born with congenital heart defects including a single ventricle rather than two and a rare condition called heterotaxy syndrome, in which her organs were abnormally arranged, with her heart on the right side of her chest.

She was a magic child, full of vim and spark, and her first 4½ years weren’t so different from any other child’s. But by the age of 5 she had endured four open-heart surgeries. And she was hospitalized again and again for many other procedures. She unexpectedly succumbed to complications from one just a little over two years ago, at the age of 13.

Noah, Keith and Cecile say, was “an old soul,” who from a very early age loved to do things for others. She wanted to help animals and children with problems like her own. At 5½, after a series of surgeries, she came home from the hospital, where she had been blown away by getting a Valentine’s Day care package from strangers containing fuzzy socks, candy and teddy bears.

She asked to have a carnival welcome-home party to raise money for more of these care packages. So began the annual “Noah’s Festival of Life,” which continues on through a foundation in her name. At the time of her death, she was in the middle of a Girl Scouts project to help the homeless. She’d gotten a company to donate pillows for them and friends to sew pillowcases.

CITY BEAT: The loneliness problem in L.A. starts with traffic. Could it end with a walk? »

Keith had just returned from an extended leave after Noah’s death — followed in short order by the birth of Noah’s brother Henry — when he noticed how much Binh had declined.

“He looked tired. He was walking in slo-mo,” Keith said. A few days later, Binh brought his son to the office, as he had many times before.

“I remember just seeing Garret and it really hit home. I’m like, that’s his boy and Binh’s his dad — and it hurt me to think that Binh could waste away and die and his son and his wife wouldn’t have Binh anymore,” Keith said. “It would have hurt me until the day I died if I didn’t at least try and see if I’m even a match. What if he died a year from now and I didn’t at least try?” He told Cecile how he felt, and she agreed.

“And when they told me I was a match, it was like wow, like it was so powerful, it felt so good,” Keith said recently in the cozy living room of his Winnetka home. “Like I wish more people could feel this. Cause it’s incredible just to know what you’re able to do for somebody.”

Noah taught him, he said, that life can be cruelly short. No woulda, coulda, shouldas for him.

He and Cecile say they talk to her often, sometimes together, sometimes in her room, which still looks just the way she left it. Her menagerie of stuffed animals still waits for her. Her shelves are crowded with her Nancy Drews and the other mysteries she liked to crawl into for hours upon hours. Her dresser drawers are still covered with her stickers. Cecile has Marie Kondo’d Noah’s T-shirts into little bundles inside them.

The transplant has not been an instant miracle. Binh remains in the hospital, still weak, still adjusting. There have been some hitches, which they are trying to work out.

On Saturday night, I was in Binh’s room when Keith, wearing his hospital gown and yellow socks with the no-slip treads, wheeled his IV pole in, hunched over, taking mincing steps, wincing and at the same time beaming. Binh, similarly attired, was in a chair, firmly gripping the button that administered his pain meds. They gently leaned their bodies toward each other to embrace. It wasn’t easy. Both ached.

When Keith and Cecile headed back exhausted to their room a few floors higher in a different tower, Karen and Binh talked about their kindness and the meaning of kindness to others on any scale.

They were lucky that Binh’s employer has been so generous, that a tribe of friends has surrounded them and kept Garret busy.

Really, said Karen, at the heart of it all, theirs is a story about being seen.

Like the small community that has encircled them in care, Keith saw Binh, saw his need and he did not avert his glance or walk away.

Nita Lelyveld wants to know your L.A. story. Email her at citybeat@latimes.com.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.