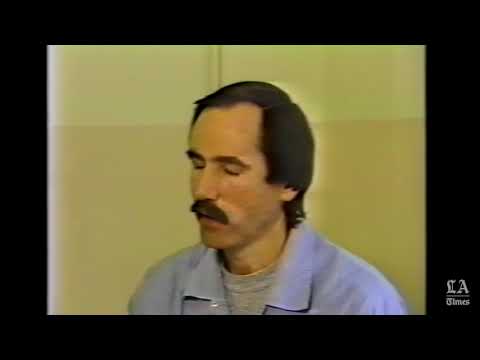

‘Pillowcase Rapist,’ who was living in L.A. area, must be confined to a state hospital, judge rules

Christopher Hubbart was convicted of two separate series of sexual assaults. He spent nearly 20 years in a state mental hospital under California’s Sexually Violent Predator law. Hubbart offered a window into his crimes back in 1994, when he was int

- Share via

A judge in Santa Clara County ruled Friday to revoke the conditional release of a notorious serial rapist who had been living in a home in the Antelope Valley after leaving a state mental hospital in 2014.

The decision by Santa Clara County Judge Richard Loftus means that Christopher Hubbart will again be confined to a state hospital, where he was locked up as a sexually violent predator for nearly two decades. He will remain confined for at least a year, according to the Los Angeles County district attorney’s office.

The revocation came after Hubbart’s treatment team informed the court he had violated several terms of his release, including failing five polygraph tests. He also refused to participate in treatment in a “meaningful manner,” withheld important information and wasn’t transparent with his treatment providers.

Hubbart — nicknamed the Pillowcase Rapist for his pattern of covering victims’ heads during his attacks — has admitted to at least 44 sexual assaults across the state.

“Christopher Hubbart is a prolific serial rapist, and even after years of treatment, he remains a danger to women,” Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey said in a statement.

Hubbart’s attorney didn’t return calls and an email seeking comment.

When the 65-year-old moved into a small house on a dirt road outside Palmdale in the summer of 2014, his arrival brought panic and outrage to the community. Neighbors gathered outside the home to protest, carrying “keep out” signs and waving pillowcases in the air.

The demonstrators, who protested for months, pressured a water company to stop delivering to the home, and law enforcement investigated anonymous death threats against the unwelcome neighbor. Before long, Hubbart — who was monitored by guards around the clock — built a fence. The healthcare company overseeing Hubbart’s treatment wrote to tell a judge that the demonstrations were “wearing the client down.”

Under the conditions of his release — detailed in a 16-page document — Hubbart agreed to several restrictions, including wearing a GPS bracelet, not calling phone sex lines, staying in his home after 9 p.m., and avoiding television shows, movies or digital media that “act as stimulus to arouse.” He also promised to keep a log of any sexual thoughts involving past victims and “maintain full transparency” with his treatment providers.

In August, Hubbart’s treatment providers filed a petition with the court asking to have his outpatient treatment revoked and Coalinga State Hospital police officers arrested him at the Lake Los Angeles home the same day.

In his Friday ruling, the judge laid out many of the treatment team’s worries.

Alan Stillman, who supervised the outpatient treatment, said he was concerned with Hubbart’s “thoughts and fantasies,” which came up in discussions about the failed polygraph tests. The therapist said he believed Hubbart was “not coming to grips with his distorted thinking,” adding that the polygraph examiners believed Hubbart had taken “counter measures” to throw off his results, including using labored breathing and putting pressure on a cuff that measured his heart response.

Stillman also said housing Hubbart in L.A. County was “horrible.” The judge noted there were protests and death threats, which caused “significant stress” that “ultimately had consequences in his treatment.”

According to the judge’s ruling, Hubbart told another member of his treatment team that he felt “between a rock and a hard spot,” saying he feared what would happen if he was totally forthcoming in his polygraph test.

The judge accused the Sheriff’s Department of being “less than cooperative with the outpatient team, hampering success of the placement.” And he blamed the district attorney’s office for Hubbart’s withholding information from his polygraph test, saying that prosecutors had interfered with his therapy by repeatedly seeking revocation.

“Their actions, therefore, undermined the treatment,” the judge wrote.

Deputy Dist. Atty. Karen Thorp disagreed, saying she acted because Hubbart was violating the terms of his release.

“Hubbart is a danger to the community and to himself — a grave danger,” she said. “We’re relieved for the community that he is back in Coalinga receiving treatment.”

Hubbart’s attacks date to at least the early 1970s, while he was living in Southern California and working at his stepfather’s furniture factory.

In 1972, he was confined to a state hospital — where he was classified as a mentally disordered sex offender — for a series of sexual assaults in the Pomona and San Gabriel valleys, according to court records.

Within months of his release in 1979, he’d started to attack again. He was arrested two years later for attacks in the Bay Area and sent to prison for eight years. Two months after his release, he attacked again, this time sneaking up behind a jogger and grabbing her breasts.

During his time behind bars, politicians portrayed him as a poster child for why the state should lock up its most dangerous sex offenders even beyond their prison terms. In 1996 — shortly before his scheduled release from prison — Santa Clara County prosecutors asked to have Hubbart sent to a mental hospital under the state’s new Sexually Violent Predator law.

He became the first person ever held using the law, which allows the state to confine predators in hospitals if they have a mental disorder making them likely to reoffend. At his civil commitment trial, two state doctors testified that Hubbart had severe paraphilia — deviant sexual behavior.

Cheryl Holbrook, who lives a few miles from the home where Hubbart was living, said his arrival in her neighborhood two years ago horrified her. She began to have racing thoughts and imagined Hubbart breaking out of his home and attacking women. She installed cameras at her home and always kept her gun nearby.

When she learned of his arrest in August, she broke down in sobs and her body began to shake — she was ecstatic, she said. And when she heard details of why he’d been arrested, she felt even more relieved he was confined.

“To fail a polygraph five times?” she said. “Inexcusable.”

She expressed tempered optimism Friday, saying she’s still concerned Hubbart can ask to be conditionally released again in a year.

“It’s better than nothing,” she said. “But he needs to stay in until he dies. He needs to rot in there.”

For more news from the Los Angeles County courts, follow me on Twitter: @marisagerber

ALSO:

5 accused of helping suspect evade capture after killing of L.A. sheriff’s sergeant

$50,000 reward offered after young woman is killed in hit-and-run in downtown L.A.

UPDATES:

6:00 p.m.: This article was updated with details from the judge’s ruling and a quote from the Los Angeles County prosecutor.

4:10 p.m.: This article was updated with comments from Cheryl Holbrook and with additional background about Christopher Hubbart’s arrest in August.

This article was originally published at 12:45 p.m.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.