L.A. faces skyrocketing costs for lawsuits over bike crashes

On a clear morning in Porter Ranch, a 62-year-old man riding his bicycle along Reseda Boulevard struck a ruptured piece of pavement pushed up by a tree root, crashed and broke his neck, and became a quadriplegic.

Another cyclist suffered a brain injury when he struck a pothole and crashed in Sherman Oaks. A third died in Eagle Rock after hitting a patch of uneven pavement and flipping over his handlebars.

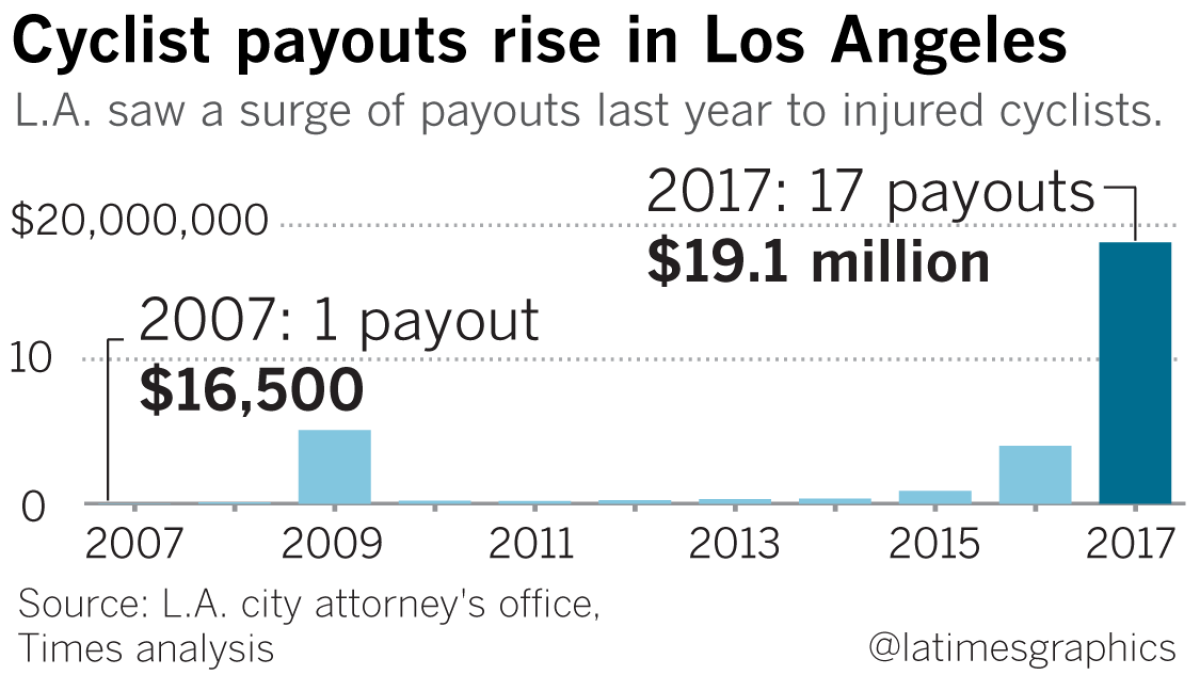

Faced with a string of lawsuits over grisly crashes, the city of Los Angeles paid out more than $19 million last year to cyclists and their families for injuries and deaths on local streets. The amount is nearly four times higher than any other year during the last decade, according to a Times analysis of city records.

The surge has defied city efforts to brand Los Angeles as a place that welcomes bicyclists, and comes as officials trumpet that its streets have improved. The Bureau of Street Services says it reached “a historical high of 4,821 lane miles” paved in the past two budget years, bringing the average grade of city streets up to a C+.

But fixing the most badly broken streets is so costly that the city has instead focused on preventing salvageable roads from sliding into disrepair.

As a result, the worst streets have remained largely untouched, including some streets where bike lanes were installed. A Times analysis found that 19% of the city’s bike lanes and routes — or about 179 miles — are on streets graded D or F.

Funding for the Bureau of Street Services has rebounded since the recession, budget records show. But the department has not spent all of that budgeted money, saying it has had trouble filling all its vacant positions.

And in many of the costliest legal cases, the city did not fully repair damaged streets despite sending crews to do other work in the area or receiving complaints from residents.

Victims and attorneys complain that city employees have ignored obvious hazards as they go about their work, strolling past dangerous potholes as they go to fix another part of the road, or striping bike lanes on plainly broken streets.

“It’s kind of a case of not-my-job-ism,” said Joshua Cohen, an attorney who represents injured bicyclists and sits on the board of the California Bicycle Coalition. “All they know is that the work order is telling them to do something — and that’s all they’re going to do.”

The crash that led to the biggest payout of the past year — a $7.5-million settlement with the 62-year-old cyclist who became a quadriplegic — happened in a bike lane that was installed on a broken roadway, then left in shoddy shape despite repeated complaints, according to a confidential settlement report prepared for lawmakers and obtained by The Times.

- Accident Date: September 7, 2014

- Payout: $7.5 million

- Street rating: F

Just before the crash, the ruptured pavement on Reseda Boulevard was inspected by the city before it was cut for utility services, “yet no inspector reported the substandard bike lane,” the report said.

One expert links the rising costs to a shift in city practices.

Years ago, the Bureau of Street Services had its supervisors inspect the roads in their areas annually, said Gary Gsell, who retired in 2014 after 46 years with the bureau. That practice was abandoned roughly five years ago, Gsell and another Street Services official have testified in depositions.

"They have changed it from, ‘We do everything we’re supposed to do’ to ‘There’s too much for us to do — now we have to wait for someone to complain,’” said Michael Green, an attorney who has represented injured cyclists.

The Bureau of Street Services said in a written statement that as of October 2016, major streets are inspected four times a year, although residential streets are not.

The bureau added that it checks for any needed repairs “at or near” the addresses where it gets a complaint. Those repair crews also fix any hazard “in the immediate vicinity” of the requested job, the bureau wrote.

But in some costly cases, that has not been the case, attorneys say.

Nearly a decade ago, Los Feliz resident Patrick Pascal had complained to city officials about rutted concrete on Griffith Park Boulevard that some cyclists call “the cracks of death.” A City Council aide told him that officials planned to repave the streets, but they never did.

- Accident Date: January 3, 2015

- Payout: $200,000

- Street rating: C

Three years ago, as Pascal and his wife biked to an Atwater Village bakery for breakfast, his back wheel jammed in a gaping crack. Pascal pitched forward across the handlebars and hit the pavement, breaking his right wrist and cracking his pelvis in two places. The crash permanently limited the motion and strength in his right arm.

“It had been neglected for a long time, with only piecemeal corrections,” said Pascal, who sued the city over the incident. Los Angeles paid him $200,000 last year to settle the lawsuit.

City Atty. Mike Feuer and Street Services general manager Nazario Sauceda declined to be interviewed about the rise in payouts tied to bicycle crashes. Mayor Eric Garcetti said he was unable to explain the surging costs, but said the city is working to improve coordination between departments that repair and maintain streets.

“Sometimes we were getting the heads up on a street that needed repairs, or people complaining that something was unsafe, and it could go to five or six different places,” Garcetti said. “That’s being changed.”

Most big cities have a single department that manages most or all programs related to their streets, but L.A. does not, according to a consultant who studied its street infrastructure programs for the city.

Los Angeles suffers from a "lack of coordination" and "undoing and redoing of work" as a result, her report found. The consultant also concluded that the city has been hampered by a "reactive" approach to potholes and other street maintenance work.

The city has already made some changes: The Transportation Department has started to survey streets before installing bike lanes to make sure that the pavement meets state standards, according to the confidential report on the $7.5-million settlement. L.A. could finally start repairing some of its worst roads this year with funding from state and county tax increases.

Garcetti stressed that since he took office, the average grade of a street that has gotten a new bikeway is a B. To grade L.A.’s streets, workers drive around the city in a van equipped with cameras and lasers. The city scores each street segment on a 100-point scale and converts those scores to letter grades, with 40 and below considered an F.

Some lawmakers want the city to go farther to curb liability: In reaction to the surging payouts, Councilman Mitch Englander proposed that the city stop installing bike lanes on streets rated less than an A — and suggested closing or removing any bike lanes on such streets as well.

Englander said that striping a broken street with bike lanes gives cyclists “a false sense of security” and increases city liability.

“Putting up signs and paint says, essentially, ‘It’s safe to ride a bike in this area,’ when it’s not safe,” Englander said. “In a perfect world, I’d recommend that we would repair the streets. The problem is, we have a massive backlog.”

Bicycle activists have bristled at his proposal.

“It’s not going to change a darn thing,” said Ted Rogers, editor of the website BikinginLA.com. “People will still ride those same streets ... and the city will face even more liability because they removed a safety feature.”

They point out that one of the biggest payouts in the past year — a $6.5-million settlement with a bicyclist who suffered a severe brain injury — stemmed from a crash that did not happen in a bike lane.

- Accident Date: May 2, 2015

- Payout: $6.5 million

- Street rating: C

Months before Peter Godefroy crashed, someone reported an “uplifted street” on Valley Vista Boulevard and a city crew was dispatched to do a “small asphalt repair,” according to court records.

Yet just before the incident, a Street Services inspector who was called out to the same site noted that there was an uplift on the roadway, and there was no evidence that the city took any steps to fix it at that time, the court records state.

“They went out, they looked at it, and they did a half-assed repair and just left it there,” said attorney Spencer Lucas, who represented Godefroy.

The Times requested data from the city attorney on all legal payouts tied to bicycle accidents in the past decade. Reporters then combed through court records and eliminated lawsuits over city employees driving vehicles or opening doors that hit bicyclists, as well other cases that had little or no link to bicycle crashes. Some court files had been destroyed or could not be located.

The spike in city payouts for bicycle crashes is part of a broader increase in legal costs across the city. A decade ago, Los Angeles spent roughly $36 million per year on settlements and other court payouts. In the last budget year, the bill was more than $200 million.

Alarmed by the swelling costs, Garcetti and other city officials have launched a “risk-reduction Cabinet” to try to reduce legal liability of all kinds.

But broken pavement has cost the city more than money, victims say.

Pascal, the cyclist injured on Griffith Park Boulevard, said the claim and settlement process left him disillusioned and frustrated. City officials tried to discount his claim at every step, he said, rather than accept responsibility for their mistakes.

“Clearly, the city is writing a lot of checks,” Pascal said. “But they’re also incurring other costs as well. I’m a less engaged citizen now. I’m less trusting of my city. It wiped out a lot of goodwill.”

Twitter: @AlpertReyes

Twitter: @laura_nelson

Twitter: @bposton

Times staff writers Jaclyn Cosgrove, Michael Livingston, Alejandra Reyes, Ellis Simani, Iris Lee and Yadira Flores contributed to this report.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.