Must Reads: Ridgecrest earthquake mystery: Why so little destruction from huge temblors?

- Share via

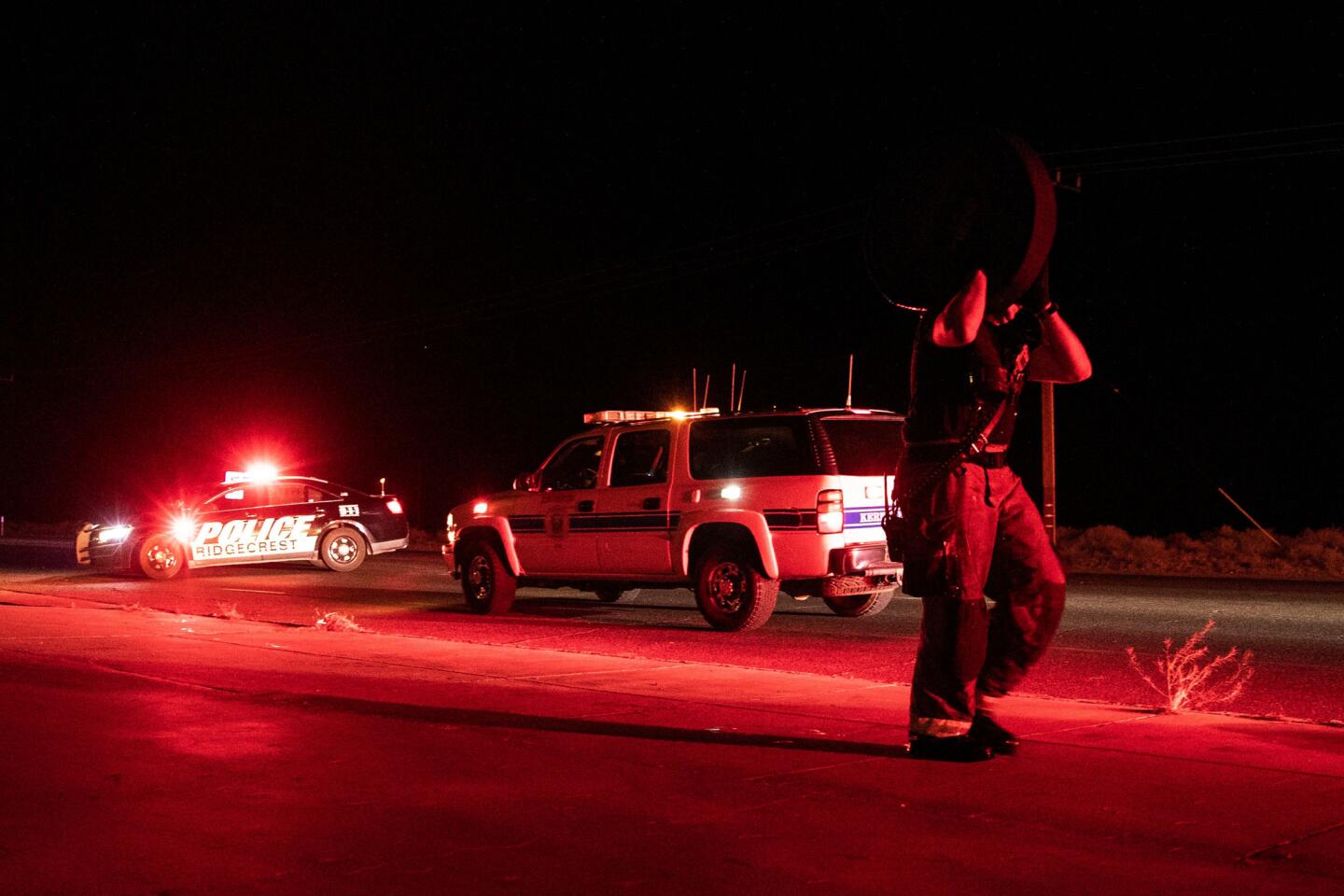

After major temblors on July 4 and 5, structural engineers descended on Ridgecrest expecting to study destruction from the largest earthquake to hit Southern California in nearly 20 years.

They found relatively little.

Yes, mobile homes were torn off foundations, chimneys fell, gas lines leaked and some homes caught fire. But overall, most buildings did fine — and many businesses were up and running within a day or two of the biggest shock, a magnitude 7.1.

“Ridgecrest, I’m just amazed,” California Earthquake Authority structural engineer Janiele Maffei said of the light damage.

But the outcome in Ridgecrest shouldn’t provide solace to California’s biggest cities.

The Mojave Desert town remained largely unscathed because its building stock was relatively new and remarkably resilient. Many homes are one or two stories, built in the 1980s. It lacks the kind of structures that experts say are most vulnerable in a big quake — unreinforced masonry, brittle concrete, so-called soft story apartments and single-family homes not bolted to their foundations.

Is my building vulnerable in a big earthquake? Here’s how to find out »

As a result, Ridgecrest suffered far less damage than cities hit by less powerful quakes in recent years, including Napa and Paso Robles, where older buildings in the downtown areas crumbled amid the shaking.

Experts were quick to point out that last week’s quakes would have proved far more devastating had they been located near bigger cities filled with more susceptible buildings.

“You take a 7.1 and put it into the Hollywood fault or Newport-Inglewood fault in Long Beach — we’re going to see substantially different levels of damage,” said Ken O’Dell, president of the Structural Engineers Assn. of Southern California. “Ridgecrest did a very good job surviving this particular 7.1.”

Keith Porter, a nationally renowned earthquake engineer and research professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, said Ridgecrest’s result should not be seen as a “victory lap.”

“We still have dangerous buildings, and we still have a building code that is not optimal and doesn’t protect society as well as it could,” he said. “Instead of a dozen collapsed manufactured homes, hundreds or thousands of collapsed manufactured homes. Instead of four or so building fires, hundreds of building fires.”

Progress has been made by cities — Los Angeles and San Francisco among them — to require some building retrofits. But even those large population centers have not mandated retrofits of all the types of structures engineers worry about. And authorities in many suburban areas — including in Silicon Valley, San Mateo County and the beach cities of L.A. County’s South Bay — haven’t ordered flimsy apartment buildings to be strengthened.

Many cities in Riverside and San Bernardino counties haven’t required fixes to brick buildings, a vulnerability Californians have known about for a century.

A U.S. Geological Survey simulation said a plausible magnitude 7.1 earthquake on the Hayward fault in the Bay Area could kill 800 people, burn the equivalent of 52,000 single-family homes and displace 400,000 people, worsening the region’s housing crisis.

And a hypothetical magnitude 7.8 earthquake that would send violent shaking waves along a 186-mile section of the southern San Andreas fault could kill 1,800 people, leave 50,000 injured and cause lasting harm to Southern California’s economy.

Such a direct hit “would take days or weeks to get to the place we are [at in Ridgecrest] — gearing up toward restoration and early recovery,” said Laurie Johnson, president of the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute.

Why Ridgecrest was spared

There are a number of reasons why Ridgecrest was largely spared.

The town, which began growing up the near Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake during World War II, does not have a stock of unretrofitted brick buildings like those constructed before the 1933 Long Beach earthquake, said USGS seismologist Susan Hough. Unretrofitted brick buildings are a major killer in quakes, causing at least five deaths in San Francisco during the 1989 magnitude 6.9 Loma Prieta earthquake and two fatalities in the 2003 magnitude 6.5 Paso Robles earthquake.

Earthquake insurance: Is it worth it? »

There are also very few “soft story” apartments with weak ground floors built to accommodate parking — likely, Hough said, a result of “having enough room to not ever need high-density housing.” A soft-story apartment collapse killed 16 people in the 6.7 Northridge earthquake in 1994.

And because they are newer, the single-family homes in Ridgecrest lacked the vulnerability of many Southern California and Bay Area pre-1980 wood-frame houses built with a handful of steps above the ground. Sharp shaking can snap the wood supports connecting such homes to their foundations. A retrofit to brace and bolt the structure can cost several thousands of dollars — but repairing the problem after a quake can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Repeating the July 4 and 5 quakes in the Bay Area and Southern California would result “in a lot of homes off their foundations,” Maffei said. “Without retrofits, the Bay Area and Los Angeles do not have resilient housing.”

There are at least 1 million of these vulnerable homes in California, but Ridgecrest has very few.

The more obvious signs of damage in Ridgecrest did not make many structures uninhabitable — cracked concrete walls surrounding yards or a broken decorative brick façade on a home, said Southern California structural engineer Wayne Chang, who visited the region Sunday and shared his observations with the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute.

Some of the worst damage was to mobile homes, which often are not secured to their foundations, engineers said.

The happenstances of geology and geography also worked in the town’s favor.

The magnitude 7.1 earthquake started at an epicenter 10 miles northeast of central Ridgecrest. But it occurred on a fault that focused the worst shaking waves away from Ridgecrest and Trona, to the northwest and southeast, respectively, of the epicenter, and into sparsely populated areas, Caltech seismologist Egill Hauksson said.

On the Modified Mercalli Intensity Scale, Ridgecrest endured “very strong,” or level 7 shaking, enough to break chimneys and damage badly designed structures but keep damage negligible in well-designed buildings. Trona got a level 6 “strong” shaking.

By contrast, much of the San Fernando and Santa Clarita valleys saw at least level 8, or “severe,” shaking during the Northridge quake — an intensity that can greatly damage poorly built structures. (The shaking nearly caused a new steel frame Auto Club building in Santa Clarita to collapse and seriously damaged or destroyed 200 apartment buildings.)

Even though the Northridge earthquake produced much less total energy than the temblor on July 5, its location caused shaking to be worse directly underneath a highly populated area.

Your instinct may be to run outside during an earthquake. Here’s why you shouldn’t »

Trona, an older city, was more heavily hit than Ridgecrest.

Although the shaking was less intense, Trona’s location on soft sediments that have eroded off a mountainside — known as an alluvial fan — caused the ground to act like quicksand, O’Dell said.

“That spreading of the soil undermined the foundations,” he said, causing the base of buildings to come apart.

Chang said Trona’s well-maintained homes seemed to withstand the shaking well, but some abandoned and unoccupied houses suffered collapsed walls.

There are few public details so far about the structural damage suffered at the Naval Air Weapons Station, which has been directly on top of recent earthquakes. Conditions have forced personnel to evacuate.

So far, authorities believe one person has died as a result of one of last week’s earthquakes — a Nevada man found pinned under his Jeep after the vehicle fell off its jacks.

What should be done

Engineers and safety advocates say more can be done before the next big quake hits California. That includes bolting bookshelves to walls, arming kitchen cabinets and clothing dressers with toddler-safe locks, and using quake putty to affix breakable items to shelves.

Porter wants lawmakers to look to strengthen the state’s minimum building requirements, which he says currently allow for construction just strong enough to not collapse in a quake.

“People think a new building is earthquake-proof. But really, all it’s supposed to do is not collapse and kill you,” Porter said. “The damage can be so costly that you can’t afford to fix it; that it doesn’t make sense to fix it.”

He urged lawmakers to reconsider a measure vetoed by then-Gov. Jerry Brown in 2018, which called for a tougher construction code to keep new buildings usable after a major earthquake.

Expect 34,000 aftershocks from Ridgecrest earthquakes. But seismic activity is slowing down »

Porter also said cities need to tackle the vulnerabilities presented by some of California’s largest buildings.

Los Angeles, for instance, has yet to decide how it wants to address the risk of steel moment frame buildings constructed before the Northridge quake; the USGS has said it is plausible that five high-rise steel buildings in Southern California could topple in a magnitude 7.8 quake.

San Francisco has yet to decide on how it wants to deal with its stock of about 3,000 potentially vulnerable brittle concrete buildings, the kind that collapsed in the Northridge and Sylmar earthquakes.

“If we think it’s expensive to fix those buildings, wait until we get the bill for not fixing them,” Porter said. If a financial district is obliterated by the collapse of a single steel skyscraper, Porter said, “who is going to want to go into all the other ones that didn’t collapse? Our trust in those buildings will evaporate.”

It’s time to move beyond simply preparing an earthquake kit as the main way to prepare for the Big One, O’Dell said.

“Being prepared is more than having your kit stocked, it’s more than having a hard hat under your bed,” O’Dell said. “We need to be preparing our buildings.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.