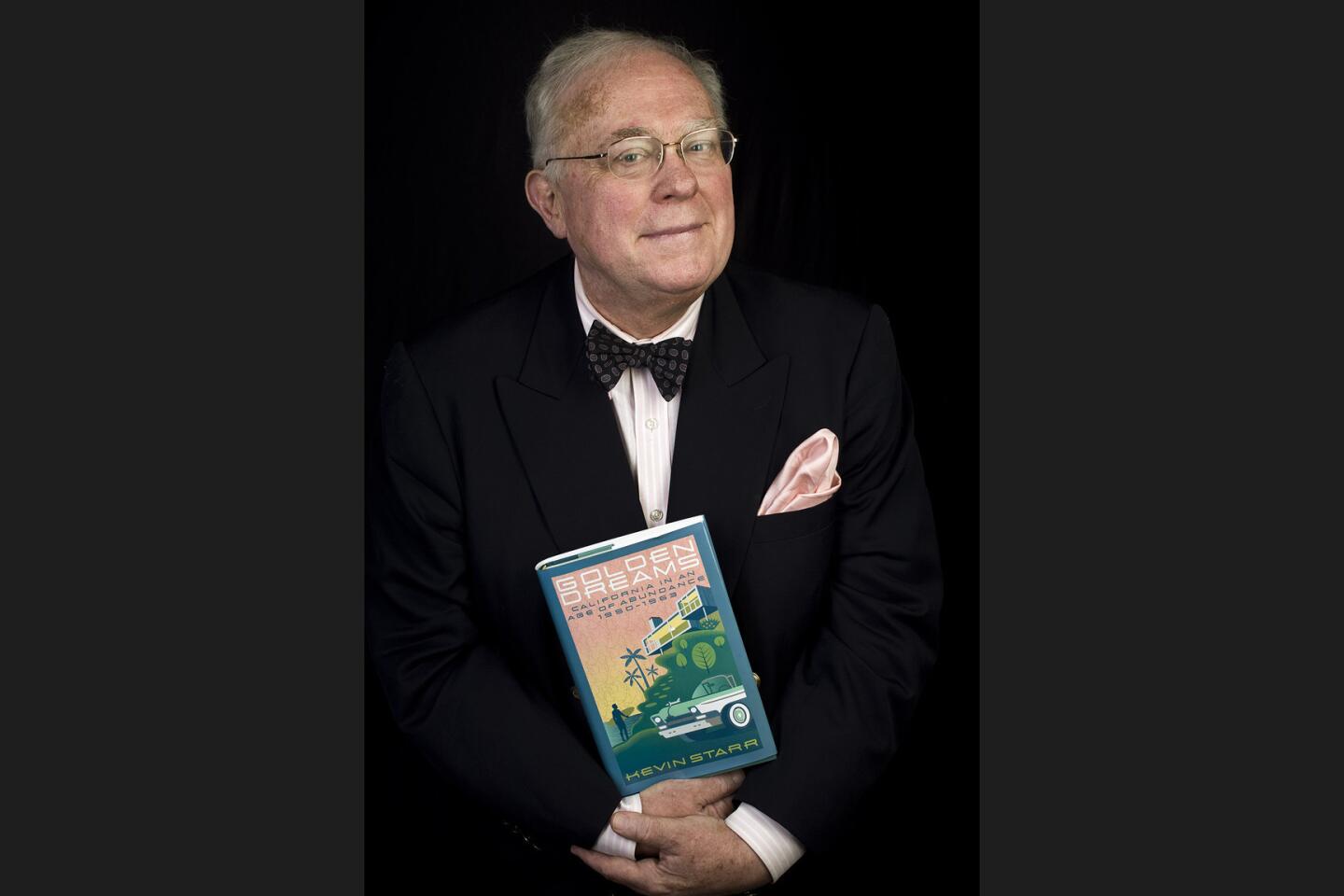

Kevin Starr, author of California histories and former state librarian, dies at 76

Kevin Starr entered this world in 1940 in a rare fraternity — a fourth-generation Californian whose family’s roots dated back to the Gold Rush era.

After a rough-and-tumble childhood in San Francisco, he found himself a graduate student at Harvard University, where he perused Widener Library’s vast collection for books about California. He realized something was missing.

“I thought, ‘There’s all kinds of wonderful books on California, but they don’t seem to have the point of view we’re encouraged to look at — the social drama of the imagination,’” Starr told The Times.

Filling this gap would become his life’s work, making him the state’s foremost historian and one of its most revered public intellectuals. For half a century, he chronicled the greed, cruelty, enlightenment, innovation, vanity and sacrifice that took California from a place of Native American hamlets through Spanish colonization, entry into the United States and growth into a diverse powerhouse of technology, culture and trade.

Starr, a professor at USC and the former California state librarian, died of a heart attack Saturday at a hospital in San Francisco, according to his wife of 53 years, Sheila Starr. He was 76.

Starr captured the state’s rise in influence, and its singular hold on the public imagination, in “Americans and the California Dream,” a sweeping book series that moves from the Gold Rush into the Progressive Era, the 1920s, the Great Depression and other distinct chapters of California’s past.

Throughout his work, Starr celebrated the state’s creativity and its openness to new ideas. And he demonstrated a familiarity with a vast range of topics central to the state’s development and its image of itself: architecture, agriculture, literature, water infrastructure and the entertainment industry, among others.

“He was the greatest historian Los Angeles and California ever had and ever will have,” said former Los Angeles Mayor Richard Riordan, who hosts a book club that counted Starr as one of its original members.

Starr graduated from the University of San Francisco in 1962 and went on to earn his PhD in American literature seven years later at Harvard University. He taught at an array of colleges, ultimately becoming a professor of history and policy, planning and development at USC.

Starr’s death drew tributes from writers, academics and both current and former politicians. USC Provost Michael Quick said California had “lost its eminent biographer.” Gov. Jerry Brown said Starr “captured the spirit of our state and brought to life the characters and personalities that made the California story.”

“His vision, like California itself, was bigger than life,” Brown said in a statement.

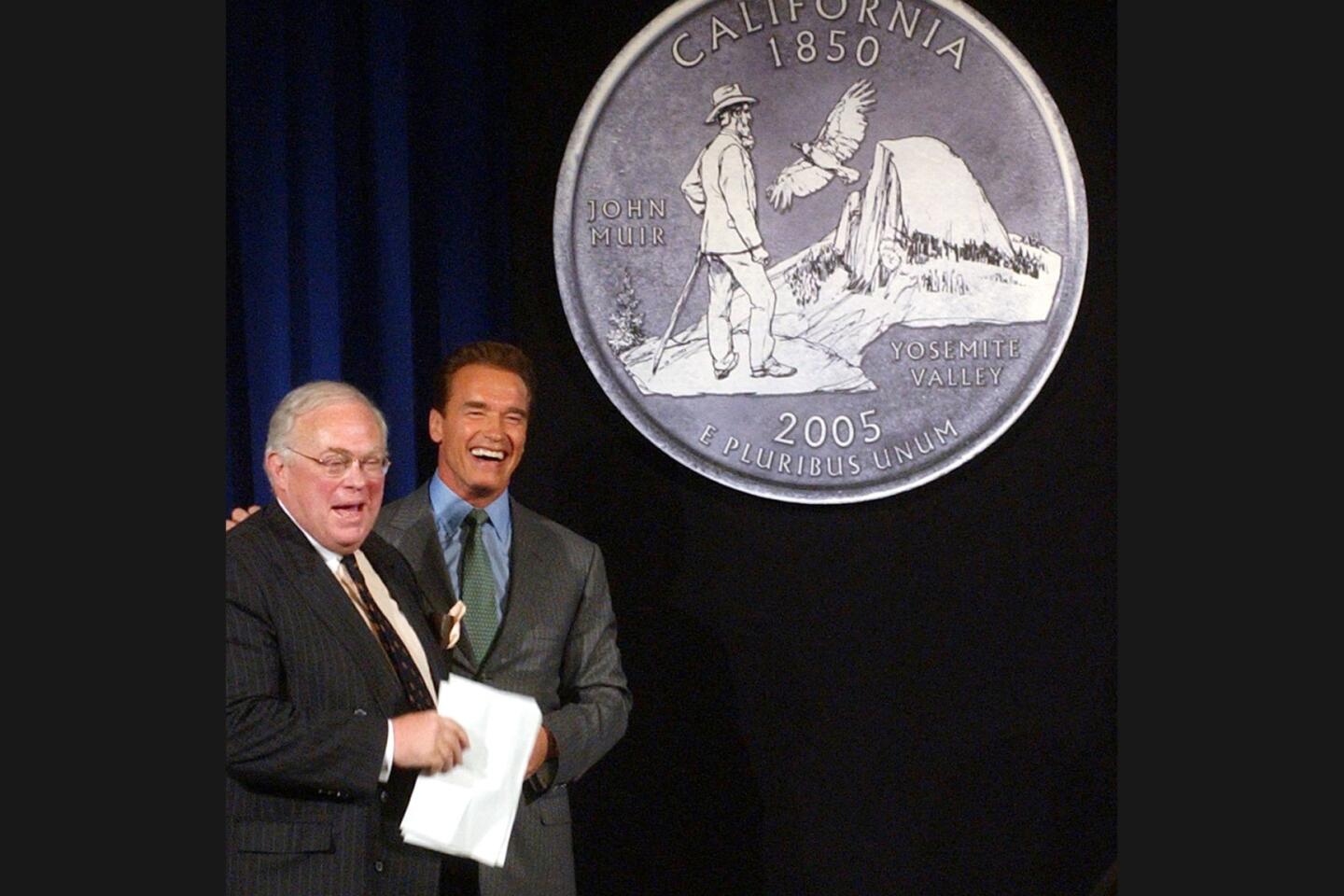

Over the course of his career, Starr served as an aide to San Francisco Mayor Joseph Alioto and later became that city’s librarian. He was appointed state librarian in 1994, holding that post for a decade. Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger named him state librarian emeritus in 2004.

Starr “loved every inch of the state” and wrote about it enthusiastically, said Los Angeles author David Kipen, founder of Libros Schmibros, a Boyle Heights lending library. But he also managed to wield influence, bringing in funds for the state’s library system.

“He wasn’t just a historian, not that that isn’t God’s work,” said Kipen, who knew Starr for nearly two decades. “Behind the scenes — and as a librarian, not so behind the scenes — he was a player.”

Starr was born Sept. 3, 1940, in San Francisco. At age 6, he and his younger brother were sent to Albertina Orphanage in Ukiah, more than 100 miles north of San Francisco, after his parents divorced and his mother suffered a nervous breakdown.

His mother eventually brought her two sons back to live in the Portrero Hill housing project in San Francisco, where the family lived on a monthly welfare check of $130.

To “emancipate” himself from the hardscrabble upbringing, he worked two newspaper delivery routes. Starr also credited the Catholic Church’s strong educational mission. He attended St. Boniface School in the Tenderloin district, and later, St. Ignatius High School, before completing his high school studies at a seminary and enrolling in the Jesuit-run University of San Francisco.

After serving two years in the Army, Starr attended Harvard on a fellowship. At that institution, he found himself increasingly interested in telling California’s history. For his thesis, he started work on what became the first volume in a multi-part series on California history.

Starr’s first entry, “Americans and the California Dream, 1850-1915,” was published in 1973. Twelve years later, he moved deeper into the 20th century, publishing “Inventing The Dream: California Through the Progressive Era.” Five years after that came “Material Dreams: Southern California Through the 1920s.”

More books, written at a rapid clip, reached as far as the 1960s. Throughout those volumes, he made sense of the state by introducing readers to influential figures such as California novelist Jack London; A.P. Giannini, founder of Bank of America; studio mogul Walt Disney; and scores of others.

“He was a storyteller. And his interest primarily was in people’s lives. He understood the power of biography to tell the story of history,” said Richard Rodriguez, an essayist who lives in San Francisco.

Starr’s sprawling series stopped at 1963, skipping the period that included the Watts riots, the Summer of Love, the Manson murders and the passage of Proposition 13, which restricted property taxes. He picked up again with a book that focused on the 1990s. Starr, said his wife, “couldn’t wrap his mind around the ’60s and ’70s.”

“He was a ’50s guy,” she said.

Starr viewed California as a special place and celebrated it like no other author, said journalist Peter Schrag, author of “Paradise Lost: California’s Experience, America’s Future.” But his upbeat outlook was tested in later decades, as California leaders confronted growing poverty and inequality.

“I think he began to have doubts later in his career, as things got more complicated and more difficult, but he never lost his enthusiasm,” Schrag said. “He was saying, ‘I see the challenging things, but I’m not going to join the crowd of naysayers.’”

That message can be found in one of Starr’s later books, “Coast of Dreams: California on the Edge,” which looked at the years 1990 to 2003 — the period when the state struggled to recover from earthquakes, riots and a steep economic downturn. In the introduction to that book, Starr said it would be “seductive” to view California as a failed experiment.

“But if I succumbed to this temptation, I would not be seeing the full truth about California and its people,” he wrote.

In addition to his wife, Starr is survived by two daughters, Jessica Starr and Marian Starr Imperatore; and seven grandchildren.

“He loved life, and he lived life in a beautiful and grand way — to the fullest,” Jessica Starr said. “We’re sorry he is no longer with us. He was taken too soon.”

ALSO

Starr on history: ‘You don’t make up your world. You find it’

Making history: a 2009 interview with Starr

Dick Gautier, best known as ‘Get Smart’s’ Hymie the robot, dies at 85

UPDATES:

8:05 p.m.: This story has been updated with more details about Starr’s background.

5:25 p.m. This story was updated with new comments from people who knew Starr and more detailed information about his professional background.

This story was originally posted at 3:45 p.m.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.