Campaign records found among Ex-L.A. City Councilman Tom LaBonge’s office documents

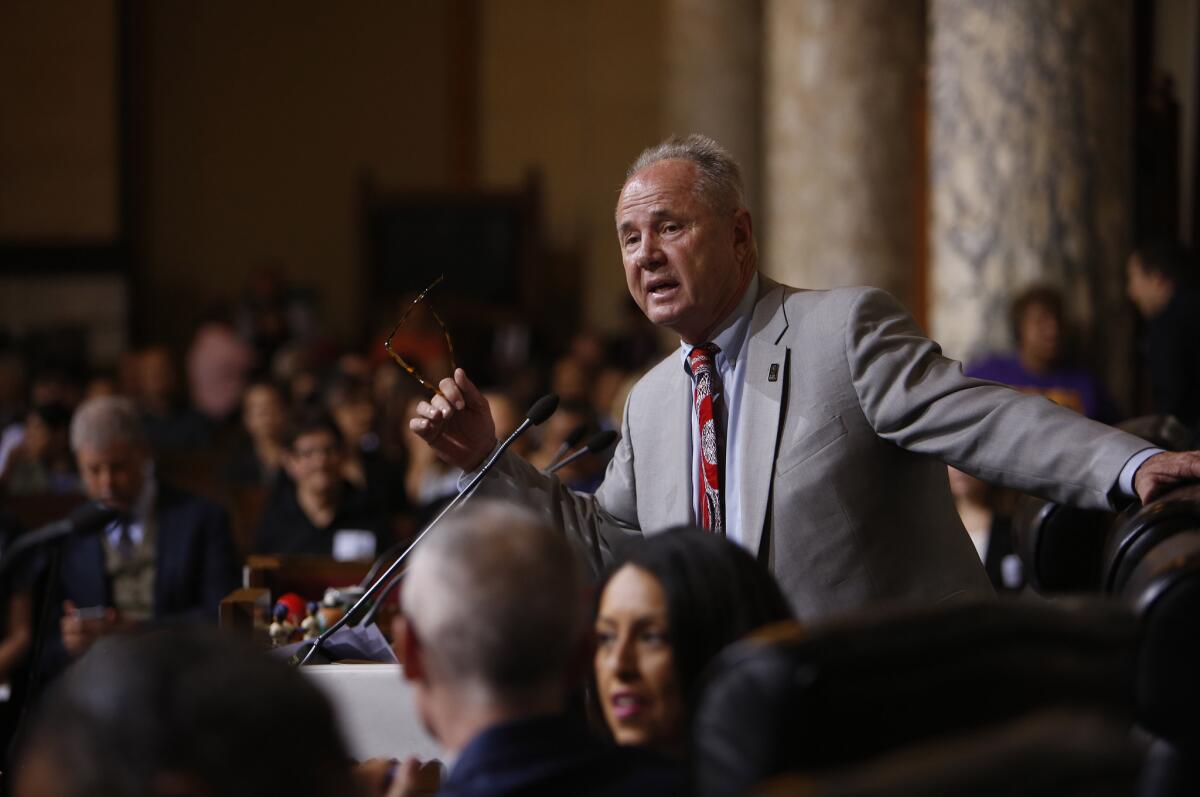

Former Los Angeles City CouncilmanTom LaBonge speaks during a City Council meeting last year. On Friday, documents from his office were made public.

- Share via

Dozens of boxes of office documents that former City Councilman Tom LaBonge and his staffers sought to destroy included old lists of election donors.

LaBonge, in an interview Friday, said he had “absolutely not” worked on his campaign at his City Hall office.

L.A. city officials and employees are prohibited from campaigning, fundraising or doing campaign research during their work hours, or in city offices not available to the public for campaign activities.

LaBonge said he did not have time Friday to review an electronic copy of the documents from his office because of a family matter.

The salvaged documents also included budget plans and piles of travel receipts related to Sister Cities, a cultural exchange program that pairs Los Angeles with other cities around the world that had come under fire during a recent campaign, along with old planning files, letters from residents and reports.

Those reams of papers had been bound for the shredder: LaBonge staffers sent 113 boxes off to be destroyed when he left office last year, according to city records. The former councilman said no one had told him to save anything and any important documents would be available elsewhere.

Dozens of those boxes were recovered by a city attorney before they could be destroyed and later sent to Councilman David Ryu, whose staff made them available to reporters Friday. Ryu and his staff had complained that when he took office, no files from his predecessor had been left behind.

The documents provided Friday included a printed table labeled “LaBonge No Money So Far” that listed people and dollar amounts for “Re-elect07” and “Officeholder06.” It had a written note attached saying, “Jeanne / Let’s talk at lunch – see me / Tom.”

Former LaBonge staffer Jeanne Min, who now works for another councilman, said in an email that she did not talk with LaBonge about campaigning in the office or during work hours and did not recall discussing the document. Min said she didn’t know why it would have been in the office.

Another printed table was labeled “Tom LaBonge Contributors 2001-2013” and listed thousands of people with their city of residence, occupations and employers, along with “Amount Rcvd.” And the documents also included an email, sent in 2003 from campaign consultant Sue Burnside, titled “tom requested a list of the endorsers- here it is,” that was sent to his wife and an aide at their personal email addresses.

Burnside, a consultant who worked on several campaigns for LaBonge, said she had never seen the former councilman violate those rules.

And some experts said the presence of such records did not, by themselves, prove wrongdoing. The fact that such papers were trashed “doesn’t mean we can show anything other than he threw the papers away in a city garbage can,” said Gary Winuk, former Fair Political Practices Commission enforcement chief.

Other records tied into a campaign controversy: During the race last year between Ryu and LaBonge’s former chief of staff, Carolyn Ramsay, LaBonge frequently faced criticism for his spending, including money allocated to the Sister Cities nonprofit by his office.

As a councilman, LaBonge had served as chairman of Sister Cities, and he and his staffers had traveled around the globe with the group. His office and the city department of cultural affairs repeatedly granted it funds for cultural programs. One of his aides, Kamilla Blanche, also served as its executive director.

Reporters were unable to get precise details about such spending during the campaign: The Times, initially believing Sister Cities to be a city program, filed a public records request for budgets and spending details going back three years. But LaBonge staffers said they did not have those records.

They referred The Times to the nonprofit, Sister Cities of Los Angeles Inc., which said it did not have to disclose such information because it wasn’t a public agency. Its tax returns also yielded little information. The nonprofit did voluntarily provide a summary of public funding it had gotten and its purpose.

And when a Los Feliz Ledger reporter started asking questions about Sister Cities budgets and accomplishments, a city analyst told Blanche not to respond until after the election, emails later obtained by The Times show.

In an email, assistant chief legislative analyst Avak Keotahian advised Blanche to say “you will be happy to assist AFTER the elections,” later adding, “again, ‘in the interest of fairness’ no information should be provided until after the elections.”

When the Ledger reporter continued pressing Blanche for information about the program, Keotahian again advised the staffer “just don’t respond – it’s clear what she’s after.”

Keotahian later told The Times he advised the LaBonge staffer to not answer the questions yet because the request appeared to be related to the campaign. Because city employees cannot get involved in elections on the job, “providing information after the elections would have eliminated any allegation … that the information was provided for campaign purposes,” Keotahian wrote in an email.

Ethics experts consulted by The Times were skeptical, however, that handing over such information would have violated city rules against campaigning on the job.

The boxes released Friday included piles of old receipts for trips tied to the Sister Cities program, including hotel bills and airline tickets for LaBonge and some former staffers.

The Times was unable to immediately discern from the receipts Friday how the travel was funded.

For instance, the documents included a city form for personal expenses that listed more than $1,600 in spending, including a hotel stay, restaurant bills and ATM withdrawals, for a trip LaBonge made to Paris. Another such form indicated that LaBonge had spent more than $2,900 in Vancouver on a 2010 trip.

But both forms were unsigned, leaving it unclear if they were submitted to the city. The city clerk’s office said it found no travel reimbursements to either Paris or Vancouver for LaBonge.

The released documents also included a budget breakdown for a celebration of the Sister Cities relationship between Los Angeles and the French city of Bordeaux, funded partly with city grants, that listed more than $15,000 in travel and lodging expenses for LaBonge and his staffers.

However, Blanche said that appeared to be a “working document” that did not account for donated lodging. She said the city grants went toward cultural programming, not travel expenses.

Seventy eight other boxes that LaBonge staff sent out for destruction have not been located and were probably destroyed, said Todd Gaydowski, who oversees city records management.

The missing files have raised questions about whether L.A., which lacks city rules on what departing council members do with their files, is in line with state laws that limit when public records can be destroyed. California law generally allows city governments to destroy some records if lawmakers and the city attorney approve, but not if the documents are unduplicated and less than two years old.

City Clerk Holly Wolcott initially told The Times that the council offices did not fall under municipal rules requiring city departments to set schedules for how long to retain records.

Wolcott later said that after additional research, she believed that the council offices did fall under those rules and would work with them to make sure they had such schedules and understood state law.

Peter Scheer, executive director of the nonprofit First Amendment Coalition, said L.A. needs such rules – for both current and exiting lawmakers -- to ensure public documents aren’t improperly destroyed.

“You can’t have any kind of freedom of information if it’s OK to destroy any public record any time,” Scheer said.

Follow @LATimesEmily for breaking news for L.A. City Hall

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.