Mexico earthquake devastation spurs California cities to action, despite the costs

A number of cities big and small in Southern California are taking steps to identify seismically vulnerable buildings for the first time in a generation, acting in part on the devastating images of earthquake damage in Mexico and elsewhere around the world.

“What happened last year in Mexico City, we don’t want to experience in California,” David Khorram, Long Beach’s superintendent of building and safety, said of the quake that left more that 360 people dead. “We want to be progressive.”

In hopes of mitigating the loss of life from a major quake that experts say is inevitable, Long Beach is discussing spending up to $1 million to identify as many as 5,000 potentially vulnerable buildings. The city of Moorpark already has agreed to spend up to $10,000 for its own survey of at-risk buildings.

Malibu is taking stock of its structures, including those with flimsy first stories — such as apartments with skinny columns holding up carport parking on the ground floor, known as “soft-story buildings.” Officials in Ventura and Hermosa Beach are doing the same.

As more cities weigh seismic retrofit laws — to protect both lives and the region’s limited housing supply — many owner and tenant groups in the Los Angeles area generally agree that earthquake strengthening should be done. But there is some concern about the cost of the upgrades and who will pay for them.

Beverly Kenworthy, vice president of the California Apartment Assn.’s Los Angeles division, said tenant safety is “a no-brainer.” Dan Yukelson, executive director of the Apartment Assn. of Greater Los Angeles, said vulnerable buildings need to be retrofitted, but added, “There’s gotta be a way to help the property owners do that.”

Most retrofits for soft-story wood-frame apartment buildings cost between $40,000 and $160,000. Upgrades to larger concrete and steel buildings can vary between $50 to $100 per square foot. Amid a strong real estate market, rising property values are giving owners more incentive to protect their investments.

Owner and tenant groups have been calling for more government support for grants or low-interest loans to help fund retrofits. On Wednesday, the Los Angeles City Council voted to study a new seismic retrofit loan program using money from sources like a city affordable housing trust fund.

“Not all building owners can afford to go into the market and get a building loan,” said Martha Cox-Nitikman, vice president for public policy for the Building Owners and Managers Assn.’s Greater Los Angeles chapter.

Some, however, say that apartments are a lucrative business, and paying for a seismic retrofit makes sense for long-term owners.

“If you look at the cost of the retrofit versus the value of the building, the mathematics are really easy. We have significant investments in these properties, and we intend to protect them,” said the managing director of Burbank-based Cusumano Real Estate Group, Michael Cusumano, who backs mandatory retrofit laws.

Some worry renters could end up footing the bills.

“At a minimum, there has to be some shared costs,” said Larry Gross, executive director of the Coalition for Economic Survival, a tenants’ advocacy group. In cities without rent control, Gross said, hikes to cover the cost of retrofitting could be beyond some renters’ means.

Dan Faller, president of the Apartment Owners Assn. of California, is among those who oppose mandatory retrofits as unnecessary government intrusion. Still, he said, the possibility of legal action if someone is injured in an earthquake means “it would behoove most apartment owners to get the job done as soon as possible.”

GRAPHIC: Look at how apartments can collapse during an earthquake »

Part of the reason of the change in discourse around city halls was Los Angeles’ landmark 2015 law enacting the nation’s most sweeping seismic regulations — covering an estimated 15,000 apartment and concrete buildings. Santa Monica and West Hollywood followed suit last year and added steel-frame buildings to their retrofit lists.

Another factor has been the entry of the Southern California Assn. of Governments in boosting talk of earthquake safety. The group hired seismologist Lucy Jones, instrumental in crafting L.A.’s law, as a consultant, dispatching her to offer presentations to a number of cities interested in doing more on earthquake safety.

Moorpark Assistant City Manager Deborah Traffenstedt said Jones’ Center for Science and Society helped link her city with others in the area. Officials now share information during monthly conference calls.

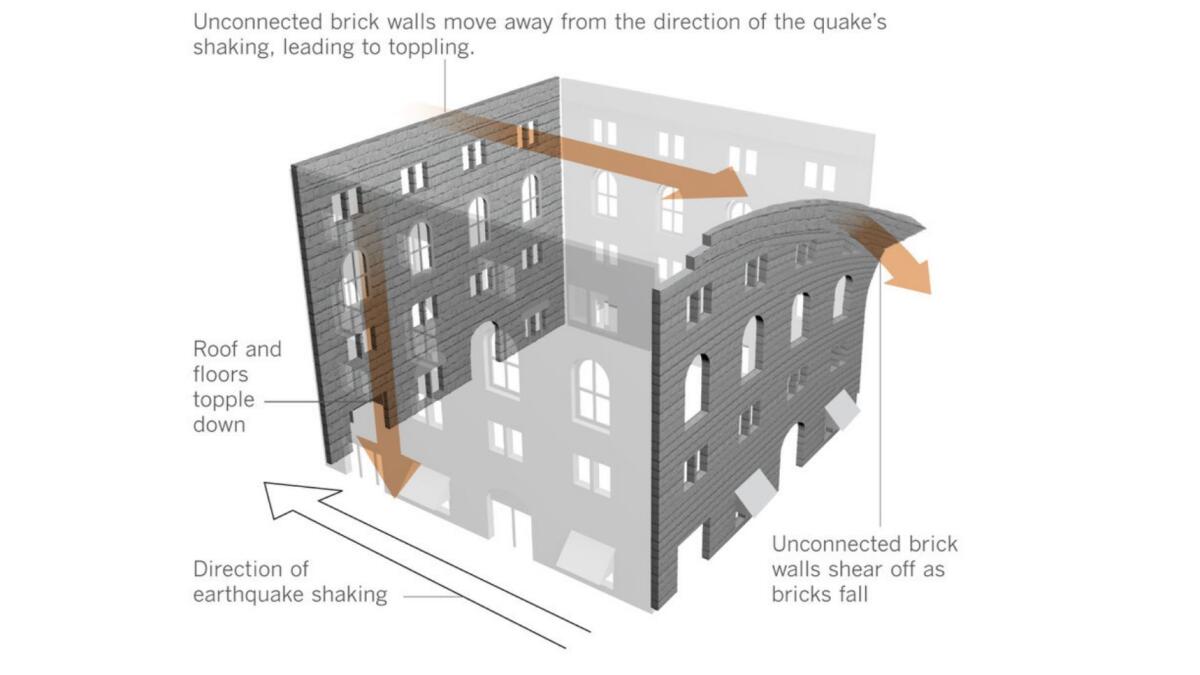

Among the most vulnerable structures in the event of a quake — and those that can be the cheapest to retrofit — are the state’s stock of historic brick buildings.

Ventura, for instance, “is one of those few historic downtowns on the coast, and we want to preserve that. That’s part of what makes Ventura special,” said Jeffrey Lambert, the city’s community development director, adding that months of paralysis after an earthquake would bring “a pretty devastating impact to us.”

An existing city law only mandates that brick buildings be retrofitted above the roof line, a minimal requirement that puts the rest of the structure at risk of collapse. Lambert said Ventura’s next step will be to establish a more comprehensive inventory of seismically vulnerable buildings and consider options that could require retrofit of brick and other buildings at risk of collapse.

In San Jose, a mandatory law on brick buildings led to more than 120 being retrofitted and more than a dozen demolished. Five old brick buildings remain, and all of those have been ordered vacated.

The city of Martinez, in Contra Costa County, had long had only a voluntary law on brick buildings, but as of a decade ago there were still about 40 nonretrofitted ones left. City leaders decided to pass a mandatory law, and by 2017 all had been retrofitted — without the city needing to pursue legal action.

“It’s an accomplishment,” said Dave Scola, the public works director. “The council said they didn’t want to keep putting it off until people here were injured.”

In Gilroy, officials moved to compel seismic retrofits by filing criminal complaints against the owners of two brick buildings who had not made progress on them. One was later sold at a county auction for failure to pay property taxes and the city bought the other property, said Kristi Abrams, Gilroy’s community development director. Both criminal cases were dismissed. Eight other buildings are in various stages in the retrofit process.

GRAPHIC: Why old brick buildings can collapse »

The city of Napa years ago passed a mandatory retrofit law for brick buildings. Some business owners initially were frustrated by the requirement, including Lewis Chilton, co-owner of Velo Pizzeria, which opened in a brick building in 2014.

But when a magnitude 6 earthquake rocked Napa just two weeks after the business opened, Chilton changed his view. The retrofit “saved our entire investment,” he said. “Yes, we had to put in extra money. Had that not been done in this particular situation, we would have lost everything.”

A neighboring building of the pizzeria was, according to the city, a non-retrofitted brick building. The owner, Brian Silver, has long opposed the retrofit law, writing to the city in 2013, “I am confident that there is no realistic danger.”

But when the earthquake struck, bricks from that building tumbled down, smashing through a parked car. According to the city, the building temporarily threatened neighboring ones, including the one Chilton leased. Neighbors built emergency protective barriers to shield themselves if the damaged building came apart further in an aftershock.

Silver said he is still opposed to the mandatory retrofit law. No engineer would ever tell him that retrofitting is a guarantee against future damage, he said.

“Retrofitting is overrated,” Silver said. “A retrofit doesn’t accomplish very much.”

Silver’s building was stabilized after the quake, but it has remained vacant and needs further work before it can be reoccupied.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.