Must Reads: He was a bouncer, she loved music, he wanted to join the Army — these are the victims of the Borderline shooting

A day after a gunman opened fire in the Borderline Bar and Grill, the city of Thousand Oaks hosted a prayer vigil honoring the victims of the shooting.

The neighborhood bar they all came to for a casual midweek night out was like one big community living room.

It was the kind of place where you might run into a Little League coach or a neighbor or the owner of a local coffee shop you liked, the kind of place where people of a wide range of ages felt secure.

It had long been a hangout of students from the colleges nearby. Every Wednesday was College Country Night.

One of those who would die after a former Marine opened fire there Nov. 7 was a college student who had recently been to the bar’s College Country Night Halloween Hoedown.

Another was a sheriff’s sergeant who quickly responded to the scene. Another was a veteran who survived the Las Vegas massacre last year.

Among the dead were a father who hoped to find his path with a coffee shop he had opened, a college freshman who dreamed of being a singer and a former Marine who devoted himself to helping fellow veterans adjust to coming home.

These are some of their stories:

Sean Adler, 48

For years, Sean Adler hopped from job to job, looking for his passion.

He was a salesman who also coached soccer and taekwondo. He trained to become a deputy with the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department — but then he had a heart attack and had to change course.

Over the summer, he proudly opened a coffee shop in Simi Valley, the town where he grew up. He called it Rivalry Roasters.

On one of its walls, a sign read: “Collect moments, not things.”

While the business got going, Adler continued working as a bouncer at Borderline Bar and Grill to support his wife, Fran, and two sons, ages 17 and 12.

He was working at the bar when he was killed.

Debbie Nieser, a childhood friend, said he had charisma.

“He was just a very caring guy that was a lot of fun,” she said. “He was someone that went after his dreams, someone who was always trying to find his dreams, someone who connected with many different types of people.”

At Adler’s funeral in December, hundreds of people gathered at Hummingbird Nest Ranch in Simi Valley dressed in Hawaiian shirts, which he liked to wear.

Friends and family said Adler tried to disarm the shooter at Borderline. A cousin shared a belief from Judaism: If you save a life, it is as if you have saved the world.

Friends, who referred to Adler by his nickname, “Dusty,” described him as a hard worker and a prankster. With his wife and two sons, he liked to cook and concoct fanciful desserts, including something his son Derek called “Diabetes” — Cinnamon Toast Crunch cereal with melted marshmallows and caramel.

Derek, 12, told the audience that when his dad was a high schooler in Simi Valley, he drove to the mountains at 4 a.m. to pack the bed of his truck with snow. He then started a snowball fight at school.

“But then it got kind of out of control and then he hit the vice principal in the head,” said Derek, eliciting laughter from the room.

Dylan, Adler’s older son, lovingly described his father as a man with a big personality. When Dylan hated school, his dad helped him work through what he found challenging. He sat down and listened to him. He knew how to make someone feel better, the 17-year-old said.

“Nobody knew how great of a father he was except me and him,” Dylan said.

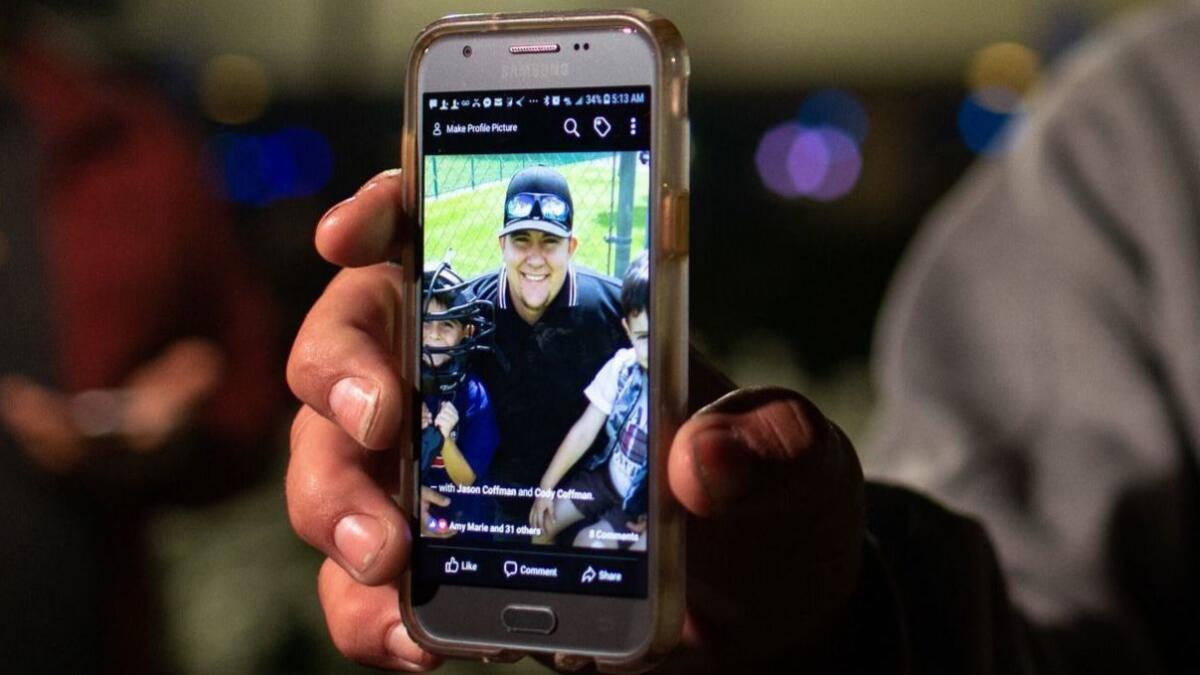

Cody Coffman, 22

The last thing Cody Coffman’s father, Jason, told his boy was, “I love you, son.”

The 22-year-old was his father’s fishing buddy, even as a small child.

“That poor boy would come with me whether he liked it or not,” Coffman said. “That’s the kind of stuff that I’m truly going to miss.”

From the moment he could walk, the younger Coffman had a ball in his hand. He had a passion for baseball and later became an umpire. He wanted to follow in his grandfather’s footsteps and join the Navy.

He was also expecting a baby sister soon.

Coffman had been living with his father for a couple of months, allowing the two to grow even closer.

“There’s nothing like your first-born best friend,” Jason Coffman said.

His son loved all kinds of music — classic rock, hip hop, country. At least once a week, he would show up at Borderline Bar and Grill to line dance.

He had gone out that night to celebrate a friend’s 21st birthday. When Coffman left his family’s home on the night of the shooting, he was wearing a new pair of pants to go with his signature cowboy boots.

“I cannot believe that it’s happened in my family,” Jason Coffman said. “I am speechless and heartbroken.”

At Coffman’s funeral, Erika Sigman said the 22-year-old helped her and friends escape from the bar.

“I don’t think any of us would still be here if it wasn’t for him,” she said.

Blake Dingman, 21

Blake Dingman was a jokester and a fixture in Ventura County’s off-roading community.

He was goofy, always trying to make people laugh, said his friend Michael Moses.

“I don’t think I ever saw him sad about anything,” Moses said.

Dingman was at Borderline the night of the shooting with his friend Jake Dunham, who also was killed.

At the joint funeral in December for Dingman and Dunham, both 21, friends remembered Dingman as someone who was always willing to help. The friend you call when your car breaks down at 3 a.m. on the side of the road.

“Blake would give and give and give,” said friend Stephanie Thurman. “If you ever needed anything, he was the first one in line to lend a helping hand.”

His mother, Lorrie Dingman, called her older son a “red-headed firestorm,” but one who was maturing into a young man.

The two recently drove to Washington state for a family member’s wedding that Lorrie helped plan. They talked about their lives and hopes and feelings, she said, and she loved seeing how he was able to express himself.

As an event planner, she always needs a right-hand man, she said.

“Blake was always that guy,” she said.

On Instagram, his younger brother Aidan Dingman wrote about learning that his “amazing brother was taken down by the shooter.”

“Words cannot describe the pain I am feeling. …. Blake, I love you so much, and I miss you more than you can imagine.”

Lorrie Dingman said her son was colorblind and she was “so thankful he’s now seeing all of those glorious colors in heaven.”

”I miss his hugs on the way out the door, as he said, ‘I love you, Mom,’ ” she said.

Jake Dunham, 21

When Newbury Park off-roaders would ride off into the desert, their trucks would rise into the air before crashing nose-first in the dry dirt. Sometimes, they would set the vehicles and old dirt bikes aflame for a huge bonfire celebration, drinking and laughing around the fire.

Jake Dunham was usually there, the life of the party, said friend Michael Moses.

Before the shooting, Dunham and fellow off-roading enthusiast Blake Dingman had planned a camping trip out in the desert for the following day.

At the joint funeral, family members remembered Dunham as someone who did not let obstacles stand in his way.

He suffered from hemophilia and had lost vision in one eye as a boy. Yet he wakeboarded and went dirt-bike riding. He loved Lake Havasu and wanted to move there eventually.

“He was the real-life fast and furious,” said Pastor George Golden. “He made every tripping stone a steppingstone.”

As an off-roader, Dunham was the gutsy one. He would drive his giant truck, towing a Ford Ranger. It wasn’t long before he’d break the truck after all the hard riding.

Then he’d drink — probably a Jack and Coke — and sit around the bonfire with friends, laughing as he plotted his next feat.

“He always tried to convince people to [let him] drive their car. Everyone knew it was a bad idea, but sometimes they’d do it,” Moses said, laughing.

His older sister, Alexis Dunham, said she and her brother were close; their groups of friends overlapped. She had imagined that one day he would try to teach her children to drive before their feet could reach the pedals.

“Words can’t describe how much I miss you,” she told the crowd gathered at Calvary Community Church in Thousand Oaks. “Until we meet again — love, your big pain-in-the-ass sister.”

Ron Helus, 54

Before he pushed through that barroom door, before his body crumpled, Sgt. Ron Helus was on the phone with his wife.

“I gotta go handle a call. I love you. I’ll talk to you later.”

The words had been uttered countless times by the Ventura County Sheriff’s veteran who was on the brink of retirement when he entered Borderline on the night of the shooting. Authorities credit him with saving lives before losing his own. He had worn a badge for 29 years — the span of his marriage, and one year longer than the life of the gunman who would take it all away.

During Helus’ funeral in November at a church in Thousand Oaks, Pastor Steve Day traced the course of Helus’ life — describing how he met his wife in a college anatomy class, how he proposed to her in a restaurant after sneaking the ring into her purse as a surprise. When she discovered it, Day said, Helus went down on one knee at the restaurant where they were dining.

“They were in the old Charley Brown’s restaurant, which is now the Borderline,” he said. “How ironic.”

Read more about Helus and the legacy he left »

Alaina Housley, 18

Music was a passion for Alaina Housley, a freshman at Pepperdine University, the place where her parents met in 1994.

She loved to sing, play piano and the ukulele. She was thinking of taking a musical theater class and had dreams of becoming a singer.

“We have a gaping hole that will never be filled,” her father, Arik Housley, said at a memorial service.

On Nov. 7, Housley had finished her homework, as well as her mock trial work, and was invited to go line dancing. She was on the dance floor with friends when the shooting started. Her friends jumped through a broken window to escape, but they lost her in the chaos.

“Alaina was an incredible young woman with so much life ahead of her,” the family said in a statement, “and we are devastated that her life was cut short in this manner.”

Luke Sides, a fellow Pepperdine student, said he met Alaina last spring on campus. She had just been dropped off by her parents and was sitting alone when Sides, 19, introduced himself. She seemed relieved to make a new friend, he said.

It didn’t take her long to make many more.

“She was just a really sweet girl,” Sides said. “Whenever I had any problems, she would always reach out and helped me.”

Dan Manrique, 33

Dan Manrique dedicated his life to service.

He served in the Marines as a radio operator. Then, when he returned from the Middle East to his hometown of Thousand Oaks, he worked to help veterans settle back into civilian life.

“He was selfless,” said his brother, Marcos Manrique, 23. “He just wanted to help this country.”

Marcos Manrique said people told him that his brother was standing in the parking lot of Borderline Bar and Grill when the shots were fired — and that he ran in to help.

“I just want him to be remembered as a true hero,” Marcos Manrique said.

Born in Mexico City, Manrique was the oldest of four siblings. He had recently gotten a good job at a nonprofit serving veterans called Team Red, White & Blue.

His sister, Gladys Manrique Koscak, said she was struck by the “awful irony” of the man who killed her brother being a veteran.

“He had spent his entire professional life helping veterans,” she said.

Manrique loved photography and cheering on the Dodgers. He loved being outside and doing anything active and would sometimes search for ladybugs with his niece. He planned to move out of his parents’ house soon and had started a craft brewing company.

“It’s going to be something we keep going in his name,” his sister said.

Read more about Dan Manrique’s work helping veterans »

Justin Meek, 23

So many people at Borderline Bar and Grill knew Justin Meek.

He was the bouncer and bar promoter — and if you mentioned his name at the entrance, you got a discount.

“See y’all tonight!!” he wrote in his final Instagram post. “Say Justin at the door.”

When Meek wasn’t working at the bar, he was helping kids with autism at Channel Islands Social Services. He helped with birthday parties, family events and also sang in a quartet.

“Justin was an exceptionally kind and gifted young man who always went out of his way to help others,” said Sharon Francis, the organization’s chief executive officer.

Several survivors of the bar shooting said Meek was shot while trying to save others. Police told his family he died a hero.

In eighth grade, Meek received a heroism award for his actions in helping another student who had broken his arm.

The recent graduate had just gotten his bachelor’s degree in criminal justice from California Lutheran University.

A friend, Michael Diaz, told of how much Meek loved his sister, Victoria Rose. When Meek’s mom became pregnant with Victoria Rose, she bought her young son a doll the size of a newborn. In the delivery room, the boy cut the umbilical cord.

“He practiced holding his sister for months before she was born,” Diaz said at Meek’s funeral. “A big brother is exactly what he was.”

The siblings grew up in a military family, moving every two years. In every home they lived in, the family had a music room. Meek was always in there, singing or teaching himself how to play the guitar and the didgeridoo. He had planned to learn the bagpipes next.

Victoria Rose followed her brother to CLU and also chose to major in criminal justice. Though the siblings have a three-year age difference, Meek liked to tell people they were fraternal twins.

“I never felt alone, because I knew he was always there,” Victoria Rose said in an interview. “He’s always been my protective big brother.”

When Meek first went to Borderline with his mom, the two knew it was a great place to be. The weekend Victoria Rose turned 18, the family drove up from San Diego to Borderline to celebrate.

Leah Marty, a friend, said Meek was always friendly, cracking jokes and planning group outings.

He once encouraged her to join a line-dancing club on campus.

“I can’t dance,” she recalled telling him. “Me neither!” he responded.

Kristina Morisette, 20

A few days before the shooting, Kristina Morisette’s dad, Michael, was nervous to see his daughter board a plane to Austin, Texas.

He worried for her safety.

His daughter was stubborn and convinced him she would be fine. And she was.

On Nov. 7, Morisette headed out to her 6 p.m. shift at Borderline, leaving her mother with a coin purse, a memento from Austin.

The Morisettes’ youngest child was later killed in the bar.

She was known to the regulars in the bar for always having a smile.

Alexis Tait, a Borderline regular, looked forward to seeing Morisette at the bar.

“She was just one of the sweetest people you’d ever meet,” said Tait, who lives in Simi Valley. “She’d always put people in front of herself.”

Morisette was talkative, and her friends were the very center of her life, her parents said.

“We could either retreat and draw our curtains or we could talk about the beauty of the things that were,” said Michael Morisette, as he held his wife’s hand in their family room in an interview not long after the shooting.

She was quick to console others or offer a friend a ride. She had just bought her first car — a 2017 Jeep Renegade — with the money she had saved from working at the bar.

“We didn’t want her life to end,” said her mother, Martha Morisette. “But we don’t want her memories now to end, either.”

Mark Meza Jr., 20

Mark Meza was a busboy at Borderline Bar and Grill who was working the night of the shooting.

At his funeral in Santa Barbara, family showed photographs Meza had taken. The funeral was held 12 days before what would have been his 21st birthday.

Meza had “the biggest heart and deepest soul,” said his family in a statement.

“If Marky wasn’t senselessly taken from us, we would be turning to him now for comfort during this unbelievably difficult time,” said the Meza family in a statement. “Marky was a genuine light everywhere he went and wanted nothing more than to make people happy and bring smiles to everyone around him.”

He attended Santa Barbara City College in 2014, according to spokeswoman Luz Reyes-Martin.

“ We are heartbroken to learn of Mark’s death,” Reyes-Martin said in a statement.

Telemachus Orfanos, 27

Telemachus Orfanos (at right in the image above) survived the mass shooting in Las Vegas last year only to be killed at Borderline Bar and Grill.

His mother, Susan Schmidt-Orfanos, could hardly speak as she sobbed over the phone not long after the shooting.

“I don’t have anything else to say except more gun control,” she said.

Orfanos, who grew up in Thousand Oaks, served two years in the Navy as a sonar technician. His friends say he was the life of the party, someone everyone knew and liked. He worked at Borderline as a security guard, and also at Infiniti of Thousand Oaks.

Marc Orfanos said his son was “extremely gregarious” with an infectious smile.

“The friend that everybody loved,” he said, describing his son as “multilayered.”

During the Las Vegas shooting, Orfanos helped get people out of the line of fire. He also helped move some of those who died. Marc Orfanos said his son had been “extremely traumatized,” by the Vegas massacre and began seeing a therapist who specialized in PTSD.

Brendan Kelly, a friend, also survived the Las Vegas massacre, where he and Orfanos helped treat injured victims. He said he believed that Orfanos and Justin Meek, another friend, died protecting others. He has tattooed their names on his shoulder.

“They were not going to let people around them be in harm’s way,” said Kelly, 22. “My kids and grandkids are going to hearing about Tel Orfanos and Justin Meek.”

Noel Sparks, 21

When Noel Sparks was born, in the summer of 1997, her parents decided to name her after her father’s sister.

Sparks’ aunt, Colette Noel Sparks, had died at age 16 in a house fire in Westlake Village. In her memory, they called the baby Noel Colette Sparks.

Her mother, Wendy Anderson, immediately “felt like there was something unique and special about Noel,” said Pastor Shawn Thornton at a memorial service held in November at Calvary Community Church in Westlake Village.

Sparks, a student at Moorpark College, loved singing, dancing, playing cello and making pottery. She never missed a chance to line dance at Borderline.

She sang at the church and led youth groups and other activities. She was especially kind to children and older adults. She wanted to sit with people and listen to their perspective, not change it.

Pastor Gary Dickey wore a kilt to the service because Sparks always liked his kilts, he said. But she teased the pastor about playing the bagpipes.

Five years ago, she sent him a cartoon of a street musician who played the bagpipes. The sign in the cartoon behind the musician read, “Pay or I play.” He had collected a lot of dollar bills.

“She said I could make more money not playing and that she was willing to start the fund,” Dickey joked.

At the end of the service, Dickey played his bagpipes, the nasal tone ringing loudly across the chapel.

While the rest of the room stayed seated, Sparks’ parents and closest family and friends filed out of the chapel. The song Dickey played was called “Going Home.”

This story was written by Times staff writers Esmeralda Bermudez, Andrea Castillo, Melissa Etehad, Marisa Gerber, Soumya Karlamangla, Corina Knoll, Sonali Kohli, Brittny Mejia, Laura Newberry, Benjamin Oreskes, Alejandra Reyes-Velarde and Nicole Santa Cruz.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.