Winds, terrain and fuel: Why the Thomas fire has been difficult to contain

- Share via

Flames as tall as a high-rise galloping up and down mountainsides. Coastal communities shrouded in smoke. Armies of firefighters on the defensive with little hope of corralling a wildfire that refuses to quit.

The scene from this month’s Thomas fire is all too familiar in the Los Padres National Forest, where jagged ridges and steep canyons of chaparral have been tinder for some of the state’s biggest wildfires.

In the course of a week, the Thomas exploded into the fifth-largest wildfire in the state’s modern record. At 231,700 acres Monday evening, it ranked just behind 2007’s Zaca fire (No. 4) and ahead of 1932’s Matilija blaze (No. 6). They all have chewed their way across the Los Padres above Santa Barbara, where an utter sense of remoteness reigns an hour’s drive from some of California’s priciest real estate.

But the very qualities that make its wilderness a beacon for hikers and the dramatic backdrop to Santa Barbara also make it a firefighters’ nightmare. The mountain ranges run east-west — in line with dry winds from the interior. Deep canyons crease country that is twisted and folded by nature’s forces. There are few places where fire crews can take a stand.

“It’s really steep,” said Tim Chavez, a battalion chief and fire behavior analyst with the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection. “The ridges don’t go anywhere. There’s no place where you can put a dozer on it and connect it to anything.”

“A big percentage of firefighting success is being in the right place with the right resources when the fire squats and doesn’t move for a couple of days and you can jump on it. This fire has not done that,” Chavez added. “It’s on the move north, east, west.”

In such difficult terrain, Cal Fire officials said they basically have no way to get crews on the ground to directly attack the western front of the Thomas fire.

Instead, crews drove out of the Ventura County Fairgrounds on Monday and headed to the residential streets in the south-facing foothills of Carpinteria, where they set up defensive positions and waited in case the Thomas came to them.

Driven by winds, topography and fuel, the fire Sunday grew by a whopping 61,000 acres, the most it has burned in a single day since Dec. 5, when it charred 63,046 acres.

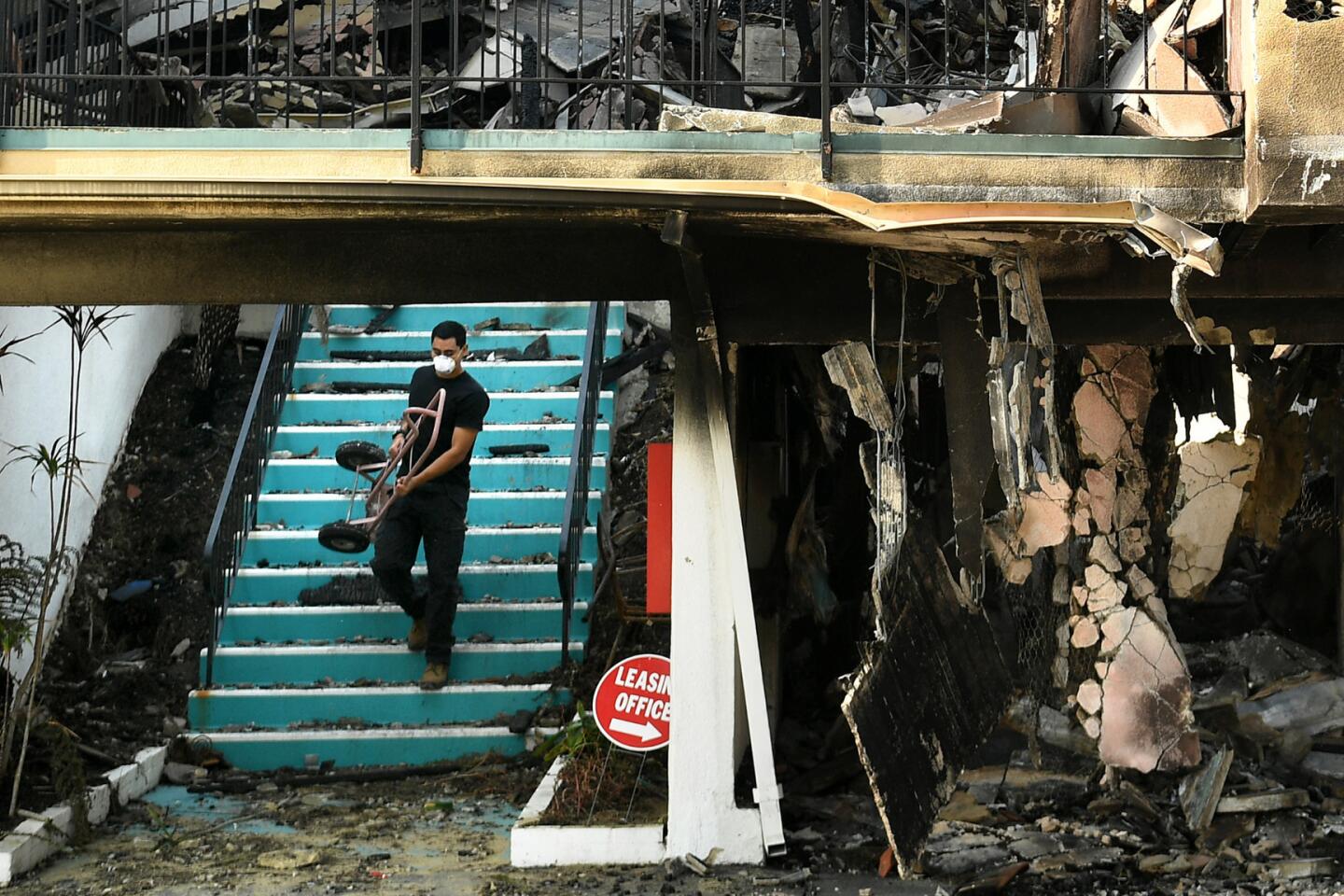

As of Monday, federal, state and local fire agencies had spent more than $38 million battling the Thomas, which was 20% contained and had destroyed more than 600 homes, most of them in the Ventura area.

The winds, which can carry embers more than a mile and start spot fires well ahead of the flame front, picked up Saturday night and Sunday morning. They also changed direction, blowing from the east rather than the northeast.

Humidity levels are stuck at withering levels, sucking the moisture out of dense stands of chaparral that can stoke flames like coal shoveled into a furnace.

Two months into the rainy season, the rains that would normally start to green up the scrublands have yet to arrive. The moisture level of live plants “hit minimum in October and stayed there,” said Forest Service meteorologist Tom Rolinski.

He expects that the winds in Ventura County and eastern Santa Barbara County will continue to blow for several more days. And though humidity levels are expected to rise at the end of the week, it won’t be by much.

“Unless you believe in miracles, I don’t see [the fire] slowing down until we get some moister air,” Chavez said. “The most hope is that maybe by the 20th, we have some weather coming. And that’s a long ways off.”

The flames have gnawed at the edges of the Sespe and Matilija wilderness areas and the Sespe Condor Sanctuary. But as of Monday morning had not made much headway into those remote areas, said Andrew Madsen, a Los Padres forest public affairs officer.

Air tankers laid retardant lines and cleared old fuel breaks to keep the blaze out of the condor sanctuary and away from a nest with a fledgling chick.

Stopping a wildfire in these lands is not easy. The Zaca started July 4, 2007, when ranch hands were fixing a water pipe on private land, sending sparks into the brush. It took two months to fully contain the 240,000-acre blaze, and pockets continued to burn until November.

But while the Zaca had a couple of explosive days, its growth was much slower than the Thomas because winds were not much of a factor.

Winds did drive the Matilija, which raged through the backcountry north of where the Thomas is now burning.

“High Wind Carries Embers Across Sespe,” declared the headline of a Los Angeles Times story that described a 100-mile fire front.

Firefighters used mule packs to get equipment into the backcountry. One horse, top-heavy with its load, fell 1,500 feet down a rocky cliff, according to the Sept. 17, 1932, article.

How you can help fire victims in Southern California »

Four days earlier, the paper ran a piece by A.L. Spellmeyer, “an expert on the wilds in Ventura and Santa Barbara counties, where the great forest and brush fire is raging.”

In a colorful testament to the region’s remoteness, the story’s headline declared: “Part of Weird and Mysterious Region Being Swept by Great Fire Has Never Been Trod by White Men and Holds Relics of Antiquity.”

“With the exception of a few trails and a few creeks and valleys,” Spellmeyer wrote, it is “a country claimed by the brush.”

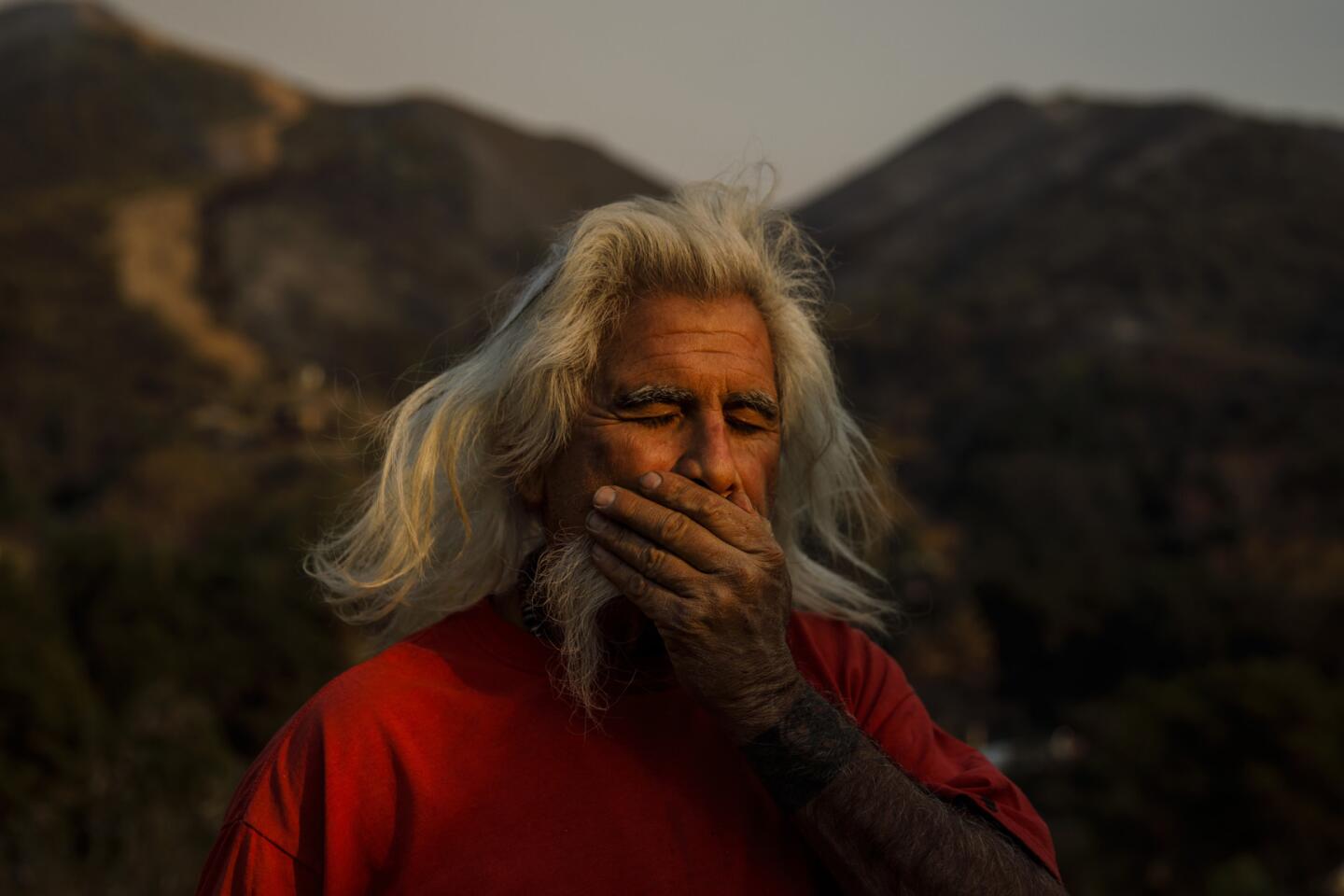

Jeff Kuyper, executive director of the nonprofit Los Padres ForestWatch, briefly returned Monday to his Santa Barbara office, which was closed because of the Thomas fire. The city was so smoky that Kuyper wore a face mask as he worked at his desk.

“It looks like a very desolate landscape in the areas that the fire has passed through,” he said in a telephone interview. “But the whole ecosystem is already at work in terms of resprouting and regenerating and pulling together the energy it needs for the new shoots.”

A decade after the Zaca fire, he added, the fire-adapted chaparral has rebounded to the extent that in some areas, “You wouldn’t know a fire had burned there.”

Times staff writer Joseph Serna contributed to this report.

Twitter: @boxall

ALSO

The inferno that won’t die: How the Thomas fire became a monster

Here are maps showing all the major fires in Southern California

Living hour by hour as the Thomas fire approaches Montecito

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.