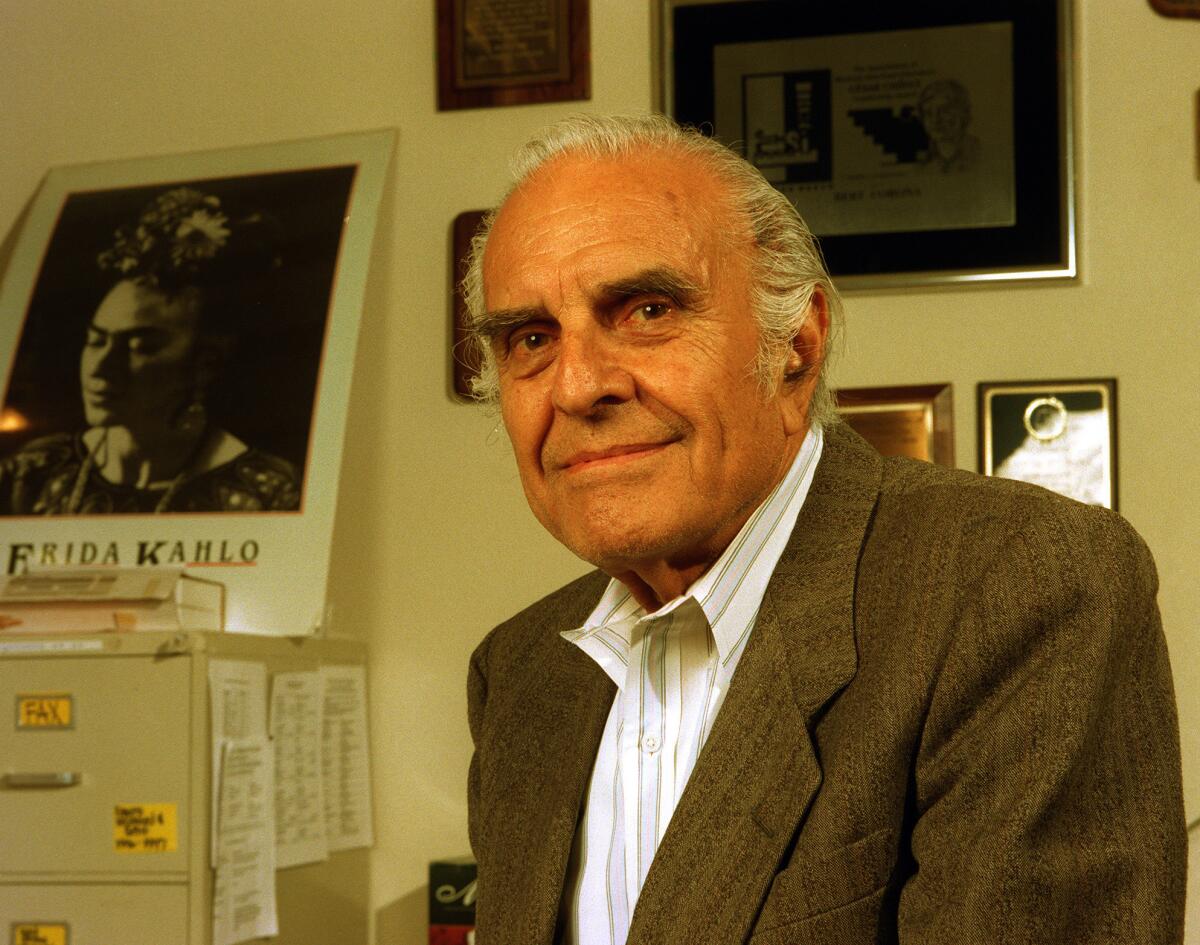

From the Archives: Bert Corona; Labor Activist Backed Rights for Undocumented Workers

Bert Corona, a sometimes fiery labor organizer, community activist and educator who championed the rights of undocumented workers, Mexicans and other Latinos in the United States for more than seven decades, has died from complications of kidney failure. He was 82.

Corona died Monday night at Kaiser Permanente Hospital in Hollywood, where he was transferred after being stricken Dec. 26 during a trip to Mexico to visit relatives, said Nativo Lopez, executive director of Hermandad Mexicana Nacional, the immigrant rights organization that Corona helped establish.

Hospitalized with an acute gallbladder inflammation, Corona underwent three operations within nine days at Hospital Aranda de la Parra in Leon, Guanajuato. He was stabilized and transferred more than a week ago to the Kaiser facility but never regained consciousness, Lopez said.

Corona was remembered as a significant figure in civil rights and labor circles whose accomplishments were sometimes compared with those of Cesar Chavez. He defended the rights of undocumented workers during a time when no one else—not even Chavez—would speak for them.

In addition to Hermandad Mexicana Nacional, Corona helped found the Mexican American Political Assn., one of the state’s oldest Latino political organizations.

“He is a giant in the history of Latinos in the United States,” said UC Santa Barbara history professor Mario T. Garcia, “but he was a lesser-known figure than Cesar Chavez. He was, however, equally as important. He did what no one had successfully done—organize undocumented workers. He is the urban counterpart to Chavez, who organized farm workers.”

Former Democratic Rep. Edward R. Roybal, who in 1949 became the first Mexican American to be elected to the Los Angeles City Council in the 20th century, hailed Corona as “a real fighter for civil rights. In the years I was away in Washington [in Congress], Bert was here all the time, fighting for things.”

Corona, whose father had fought in the Mexican Revolution of 1910, was born in El Paso. He came to Los Angeles in 1936 to play basketball at USC but did not finish college, choosing instead to immerse himself in campaigns to improve conditions for workers and fellow Mexican Americans.

In his 1993 autobiography, written with Garcia, Corona said his early interest in helping Mexican Americans in Los Angeles stemmed in part from his upbringing in the border town of El Paso, where he learned to be proud of his Mexican roots and the Spanish language.

In Los Angeles, however, he was astonished by an incident that occurred shortly after his arrival in the city. Two Mexican Americans on a streetcar ignored him when he asked in Spanish for directions to Fairfax Avenue. When they reached the stop, however, the two admonished Corona in Spanish, telling him they would have answered his question if he had spoken to them in English.

“Here it’s best not to speak Spanish,” they told him. “It’s best if they don’t know if you’re Mexican. They treat you better.”

“I looked at them,” Corona recalled, “and I couldn’t understand that attitude.”

After dropping out of college, he volunteered at a Roman Catholic Church in Boyle Heights and organized workers for the Congress of Industrial Organizations, a forerunner of today’s AFL-CIO, and the United Cannery, Agriculture, Packing and Allied Workers of America.

In 1938, he joined the charismatic labor organizer Luisa Moreno in building the League of Spanish-Speaking People, one of the first national organizations for Mexican Americans. He also helped form chapters of Saul Alinsky’s Community Service Organization in Los Angeles.

His organizing efforts in the organization often brought him into contact with another up-and-coming Mexican American Community Service Organization organizer from Northern California, Chavez, who would help establish the farm workers union in the 1960s.

While Corona generally supported Chavez and his United Farm Workers, he openly clashed with the farm labor leader over the union’s opposition to undocumented workers. Chavez and the UFW supported Immigration and Naturalization Service actions to deport illegal immigrant workers, whom they regarded as scabs.

Corona argued that undocumented workers should be organized rather than deported. That stance led him to the last great organizing effort of his life, the establishment in 1951 of Hermandad Mexicana Nacional, or National Mexican Brotherhood. By the 1960s, Hermandad began actively organizing illegal immigrants in California to improve their earning power in this country.

“I did have an important difference with Cesar,” Corona wrote in his autobiography. “This involved his, and the union’s position on the need to apprehend and deport undocumented Mexican immigrants who were being used as scabs by the growers. . . . The Hermandad believed that organizing undocumented farm workers was auxiliary to the union’s efforts to organize the fields. We supported an open immigration policy, as far as Mexico was concerned.”

Hermandad soon became a major immigrant services provider, with offices in North Hollywood, Santa Ana and Los Angeles. But by the end of 1992, federal grants, its largest source of income, dried up. In recent years, the organization was dogged by more than $4 million in debts, but Corona continued to believe in its mission.

In 1959, Corona joined with other Chicanos—U.S.-born citizens of Mexican descent—in Fresno to form the Mexican American Political Assn. As the first statewide Mexican American political group in California, the organization found its endorsement eagerly courted by Democratic and Republican candidates in the 1960s and ‘70s.

When he became the organization’s president in the early 1960s, Corona used the position to argue that Mexican American concerns deserved a presidential cabinet-rank position. In 1966, an angry Corona boycotted a White House conference on Mexican American affairs in El Paso because, he said, it was controlled by Anglos.

Corona was long active in liberal politics, working to establish Viva clubs for Democratic candidates, including Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, Sen. Robert F. Kennedy (D-N.Y.) and former California Gov. Edmund G. “Pat” Brown Sr. He was also an early supporter of former Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley.

He worked to elect Chicanos to the Los Angeles City Council, beginning in 1938 when he campaigned on behalf of a Mexican American activist named Eduardo Quevedo. Although Quevedo lost, Corona—who vowed never to run for public office—supported another Mexican American a decade later. That candidate was Roybal.

Although he never earned a college degree, Corona lectured at Stanford and taught at Cal State campuses at San Diego, Northridge, Fullerton and Los Angeles.

At Cal State L.A., where he taught for more than a decade in the 1970s and ‘80s, Corona led a faction of part-time teachers who wanted to turn the young Chicano Studies Department into an agent of social activism in the large Mexican American community surrounding the campus. Several part-time teachers, including Corona, were fired. During the turmoil, a fire was set outside department head Louis Negrete’s office and his car was set on fire in his garage at home.

When The Times characterized Corona as a Marxist-Leninist and a suspect in the fires, he sued the newspaper and Negrete. The libel suit was settled years later, with all parties agreeing not to disclose its terms.

Corona’s first wife, Blanche Taff, died in 1993. A year later, he married Angelina Castillo, who still works for Hermandad as its director of affordable housing.

In addition to his wife, he is survived by sons David, of San Luis Obispo, and Frank and Ernesto, both of Los Angeles; daughter Margo De Ley of Chicago; and three grandchildren.

Times staff writer Doug Smith contributed to this story.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.