Bob Hoskins, actor known as ‘the Cockney Cagney,’ dies at 71

Bob Hoskins, a British actor whose powerful screen presence earned him a reputation as “the Cockney Cagney” and who, at 5 feet 6 and with a face he likened to a squashed cabbage, gave the short, bald men of the world a reason to swagger, has died. He was 71.

Hoskins, who was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in 2012, died Tuesday of pneumonia in a hospital, his family said in a statement released by London publicist Clair Dobbs.

The actor was best known for playing tough guys, often with a vein of tenderness threading beneath their violent surface.

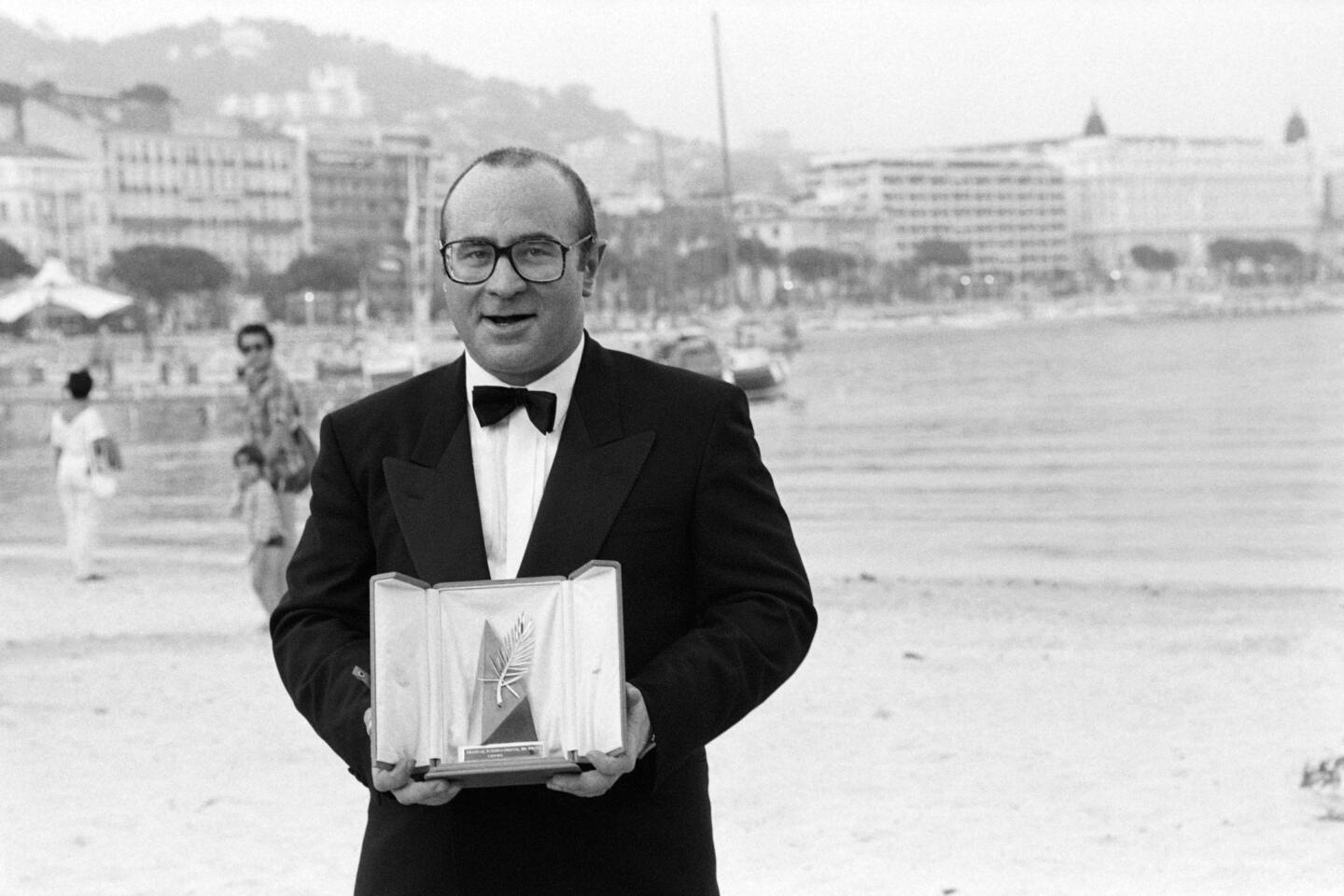

At the 1986 Cannes Film Festival, he was named best actor for his work in “Mona Lisa,” the story of an ex-con chauffeuring an elegant prostitute around London. He also received an Academy Award nomination for the part.

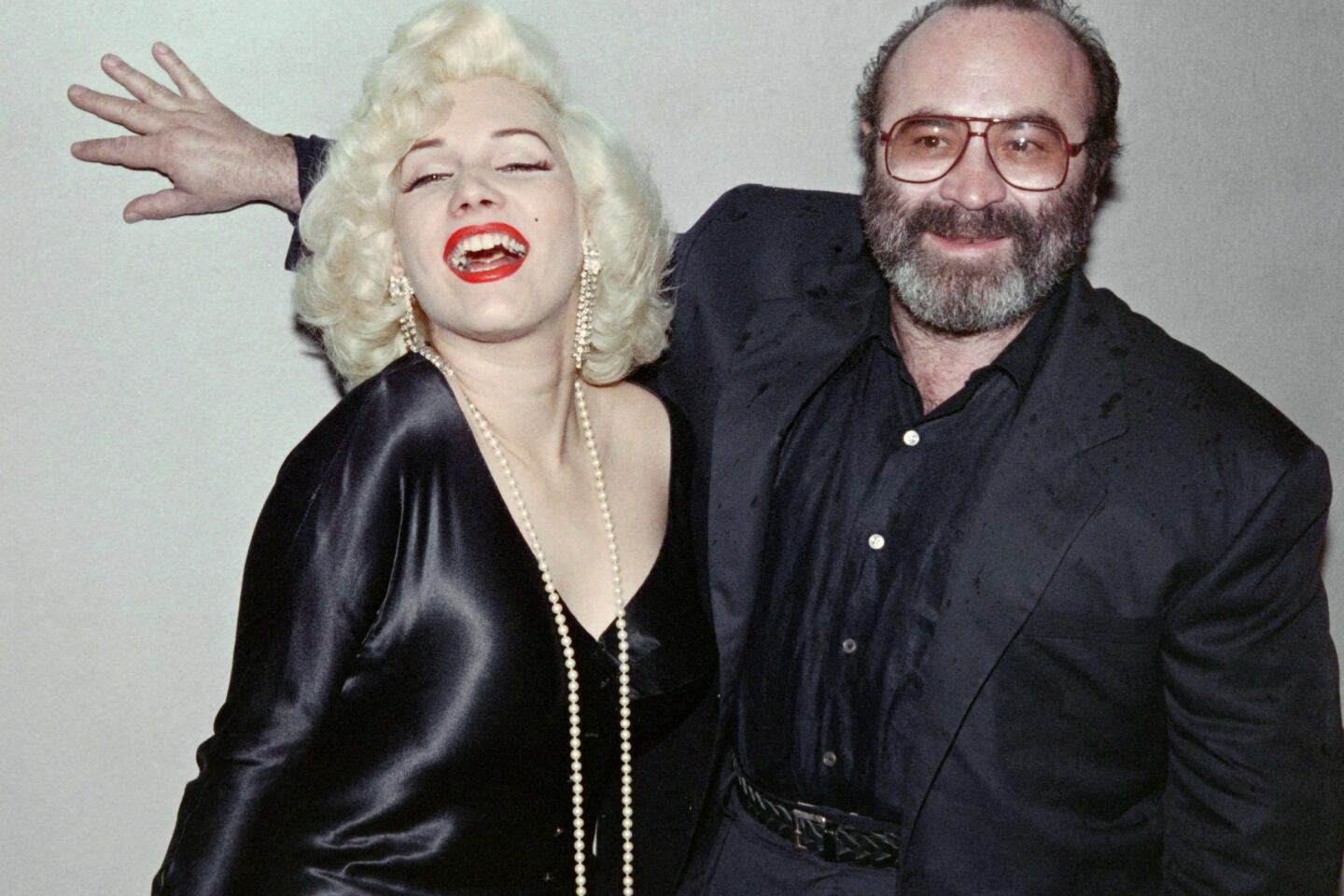

In Hollywood, he dipped into lighter fare, most famously playing hardboiled private eye Eddie Valiant in “Who Framed Roger Rabbit.” The 1988 film, which blended live action and animation, features Valiant (a softie at heart) investigating murders involving cartoon characters and a gang of weasels. He also played the pirate Smee in Steven Spielberg’s “Hook” (1991) and a handyman who was Cher’s love interest in “Mermaids” (1990).

But his bread and butter were powerful men who made their own rules: Nikita Khrushchev, Benito Mussolini, Manuel Noriega. In “Nixon” (1995), he persuaded director Oliver Stone to let him play FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover in a pink tutu.

Hoskins roamed into more ethereal roles as well. In 2005, he recalled recently playing a pope in a production on Italian TV.

“Being good was murder,” he said. “Everything, eventually, has to come from you. I had to find some little grain of goodness, which I strangled to death.”

In a statement Wednesday, actress Helen Mirren recalled her co-star in “The Long Good Friday” and other films for “that inimitable energy that seemed like a spectacular firework rocket just as it takes off.”

While he never had any formal training, Hoskins was part of “that admirable postwar lineage of charismatic British actors, from Richard Burton forward,” Times critic Charles Champlin wrote in 1986.

Like his good friend Michael Caine, Hoskins could play Americans “with lethal linguistic accuracy,” Champlin wrote, “even though his native conversational tongue is Cockney at its most aitchlessly pure.”

Wherever his acting took him, Hoskins reveled in his working-class roots.

“There was a time when people said, ‘You’ve got to speak like you don’t, walk like you don’t, be like you aren’t,” he told the New York Times in 1982. “I said, ‘Ere, ‘ang on, who am I? I’d be lost if I did that. I’d be disappearing. I’d be ectoplasm!”

Born Oct. 26, 1942, in the English village of Bury St. Edmunds, Robert William Hoskins was the only child of a bookkeeper and a nursery school teacher. At 15, he dropped out of school and took odd jobs — including, he said, fire-eating at a circus. He also took accounting classes and when he got word of qualifying for a credential, his heart sank.

“I was halfway toward being what I hated,” he once told an interviewer.

After more wandering — he did brief stints as a plumber’s mate on a Norwegian ship and as a kibbutznik in Israel — he wound up back in London, accompanying a pal to a theater where he had a job painting scenery.

As Hoskins explained many times, he was drinking at the theater bar when someone called him upstairs for an audition and plunked a script in his hands. Without even intending to, he got a part in a 1968 amateur production called “Featherpluckers.”

Working in local and regional theater, Hoskins drew national attention with his role as an amoral and imaginative sheet-music salesman in the 1978 BBC miniseries “Pennies From Heaven.”

Two years later, his first major film — “The Long Good Friday” — became an instant gangster classic, telling the story of a London underworld figure who hung reluctant informants on the tips of meat hooks.

One of his character’s speeches — a rant directed at two corporate-style U.S. hoodlums — is still famous: “What I’m looking for,” Hoskins seethed, “is someone who can contribute to what England has given to the world: culture, sophistication, genius. A little bit more than an ‘ot dog, know what I mean?”

Hoskins said he was known long afterward for his breakout role.

“The great thing about ‘The Long Good Friday’ is that it’s fantastic for road rage,” he told the Independent, a British newspaper, in 1998. “If anyone gets out their car and wants to have a fight with me, they suddenly look at me and see themselves hanging up on a meat hook, and soon bottle out.”

Conveying a menacing kind of charm, Hoskins won acclaim as the evil Iago in a 1981 BBC production of “Othello.” He became known for his sociopaths: “Hoskins is to the flick knife and the knuckle duster what Noel Coward is to the dressing gown,” a critic wrote.

But Hoskins was always self-deprecating.

At London’s Royal National Theater, he was a smash as gambler Nathan Detroit in the musical “Guys and Dolls.”

But Laurence Olivier, the esteemed actor, had been the producer’s first choice for the role and had to turn it down because he was ill.

“How’s that for something totally lunatic?” Hoskins once asked a reporter. “Me replacing Olivier?”

Such joking hid Hoskins’ intensity. After his first marriage collapsed, he lived in his Jeep for a while and had what he described as a nervous breakdown. After performing in “Roger Rabbit,” he went through a tortured time when he’d see weasels popping out of walls.

A friend persuaded him to stage a one-man show as therapy.

“She told me that if I was having a breakdown, I could have it on her stage,” he later recalled. “Afterward, she brought me a bottle of champagne and said, ‘Welcome back to sanity, kid.’’’

Hoskins brought that same intensity to preparing for his roles.

In “Mona Lisa,” he cast around for a way to research George, the freshly-out-of-jail criminal who took a fall for another mobster and falls in love with the call girl he chauffeurs.

He finally hit upon taking his daughter to the bird house at a zoo.

“We’d look at birds in their cages,” he said. “And George became like that, a man with this incredible spirit trapped inside him by his own naivete, by his own expectations, by the society around them. There he was, inside his own cage.”

For acting cues, Hoskins closely observed women.

“If you want to find out how to express something, you watch the women, and that is what I have done all through my career,” he told the Chicago Tribune in 1999. “Women can express a private moment or hidden thought without saying a word.”

Sometimes it didn’t work as planned. Starring with Maggie Smith in the 1987 film “The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne,” a tired Hoskins thought he would “just follow Maggie.”

“We started the scenes and she said, ‘Darling, I’m not a horse and you’re not a carriage. Pull your own weight, darling. We’re in this film to work together. Come on!’

“And after that,” Hoskins said, “we ate the … scenery together, you know what I mean?”

In his later years, Hoskins kept at it. His wife, Linda, would sometimes have to reassure him that they weren’t broke. The only other financial advice he took was from his old pal Michael Caine, who he said told him “never to buy an effing boat.”

Meanwhile, he was fueled by the zeal for performance he described to the New York Times in 1982.

“When I see some old guy acting his socks off, I’m proud to be in the same profession,” he said. “When it’s really flying up there, really cracking between you, it’s the most thrilling relationship in the world.”

Hoskins’ last role was as a dwarf in “Snow White and the Huntsman” (2012).

He announced his retirement because of Parkinson’s disease the same year.

His survivors include his wife, Linda Hoskins; sons Alex and Jack; and daughters Sarah and Rosa.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.