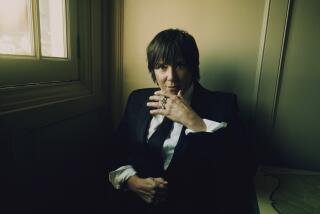

Bruce Langhorne, folk musician who inspired Bob Dylan’s ‘Mr. Tambourine Man,’ dies at 78

Bruce Langhorne, a 60s-era folk musician and prolific session guitarist who Bob Dylan said inspired him to write “Mr. Tambourine Man,” has died at the age of 78 at his home in Venice.

Langhorne was a mainstay of the folk scene in Greenwich Village in the early ’60s, playing or recording with the day’s most admired musicians — Dylan, Joan Baez, Odetta, Tom Rush, Richie Havens, Richard and Mimi Farina.

For the record:

3:33 a.m. Dec. 4, 2024An earlier version of this story incorrectly said the 1965 Newport Folk Festival was in New York. It was in Rhode Island,

But it was Langhorne’s guitar work on Dylan’s 1965 album “Bringing It All Back Home” that cemented his role as one of the architects of the emerging folk rock scene. Regarded as a seminal work, “Bringing It All Back Home” marked Dylan’s musical shift from acoustic to electric and his bittersweet farewell to the protest movement that had defined his early career.

“Mr. Tambourine Man,” a song of unrelenting insomnia and urban bleakness whose precise meaning has remained a riddle for decades, was on the acoustic side of the album. Langhorne said Dylan told him — in cryptic terms, of course — that he’d inspired the song because of the Turkish drum fitted with tiny bells that the session musician sometimes used in place of a traditional tambourine.

Though Dylan gave credit to him for inspiring the song in the liner notes of a subsequent box set, Langhorne said in an interview that the famously contrarian musician would likely deny it if ever asked.

“I think he had a wonderful ability to let people have just enough rope to hang themselves,” Langhorne told author Richie Unterberger in a two-part interview. “And I think he’d probably do that with me if he thought I was attached to being Mr. Tambourine Man.”

Born May 11, 1938, in Tallahassee, Fla., Langhorne grew up in Harlem and was a violin student until he accidentally blew off the tips of several fingers on his right hand when he picked up a cherry bomb just as it exploded.

He took the accident in stride, according to his biography on brucelanghorne.com. “At least I don’t have to play violin anymore.”

Just the same, he picked up the guitar instead and became a go-to session musician in the early ’60s, though the childhood accident forced him to innovate.

“Since I have fingers missing, some styles of guitar playing were forever unreachable for me,” he told Unterberger. In some cases, he said he was forced to play two notes with one finger to compensate for the nubs he’d been left with.

Langhorne first recorded with folk singer Carolyn Hester in 1961. Dylan, as yet unknown and unsigned, played harmonica on the recording. In a 2016 op-ed piece for the Los Angeles Times, Hester recalled her studio band — Langhorne, Dylan and Bill Lee (director Spike Lee’s father) — as being transcendent. And when Dylan later recorded “The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan” in 1963, he asked Langhorne to join him in the studio.

As celebrated as his bandmates were, the person Langhorne said he held in the most awe was a young Canadian songwriter named Joni Mitchell. Her songwriting was so sophisticated and her performances so improvisational that, for the first time in his career as a musician, Langhorne said he felt intimidated just trying to play her music.

At the Newport Folk Festival in 1965, Langhorne performed with Peter, Paul and Mary and other acts, but not Dylan, who shocked the traditional folk crowd by arriving on stage with an electric guitar and a full rock band. Critics at the time said Dylan instantly electrified half the crowd at the Rhode Island festival, and electrocuted the other half.

Langhorne played with Dylan one final time in 1973, when he was brought as a session guitarist for the soundtrack for “Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid,” a Sam Peckinpah movie in which Dylan had a bit part and yielded a hit song, “Knocking on Heaven’s Door.”

Langhorne moved to Los Angeles in the late 60s, first to Laurel Canyon, which was then teeming with musicians, artists and free spirits, and then to Venice Beach, where he was a regular participant in a local celebration known as the Venice Beach Marching Society — a loosely built gathering that enjoyed music and “good causes,” said Cynthia Riddle, a longtime friend.

He continued to perform, do session work and was so democratic about sharing his music that Riddle said he would often perform at weddings, birthday parties and family gatherings. The oversize tambourine that helped inspire “Mr. Tambourine Man” is now part of the Dylan archives that will eventually be housed in Tulsa, Okla., alongside the works of Woody Guthrie.

In the early ’90s, after being diagnosed with high blood pressure, Riddle said Langhorne called her up and sought her advice on coming up with a low-sodium pepper sauce that would allow him to continue adding the heat he so loved to his meals. Together they scoured ethnic markets in L.A. until they came up with a blend of African peppers that suited his taste and met his low-sodium need. They eventually began to market the concoction.

“He was a guy who lived in a state of perpetual wonder, enjoying each moment,” Riddle said.

A stroke several years ago robbed him of his ability to play guitar. His death April 14 was a result of kidney failure, Riddle said.

He is survived by his wife, Janet Bachelor.

Twitter: @stephenmarble

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.