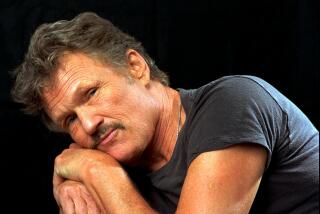

Cliff Robertson dies at 88; actor starred in films and on stage and TV

Cliff Robertson, who starred as John F. Kennedy in a 1963 World War II drama and later won an Academy Award for his portrayal of a mentally disabled bakery janitor in the movie “Charly,” died Saturday, one day after his 88th birthday.

Robertson, who also played a real-life role as the whistle-blower in the check-forging scandal of then-Columbia Pictures President David Begelman that rocked Hollywood in the late 1970s, died at Stony Brook University Medical Center on New York’s Long Island, according to Evelyn Christel, his longtime personal secretary. A family statement said he died of natural causes.

In a more than 50-year career in films, Robertson appeared in some 60 movies, including “PT 109,” “My Six Loves,” “Sunday in New York,” “The Best Man,” “The Devil’s Brigade,” “Three Days of the Condor,” “Obsession” and “Star 80.”

PHOTOS: Notable deaths of 2011

More recently, he played Uncle Ben Parker in the “Spider-Man” films.

Throughout his career, Robertson worked regularly in television, including delivering an Emmy Award-winning performance in “The Game,” a 1965 drama on “Bob Hope Presents the Chrysler Theatre.”

Robertson first came to filmgoers’ attention playing Kim Novak’s wealthy boyfriend in “Picnic,” the 1955 romantic drama starring William Holden.

While continuing to work on stage and in television, Robertson starred in a string of movies over the next seven years.

He was Jane Powell’s love interest in the 1957 musical comedy “The Girl Most Likely,” an Army lieutenant in the 1958 World War II drama “The Naked and the Dead,” a surf bum (the Kahuna) in the 1959 Sandra Dee surf-and-sand epic “Gidget” and a doctor in the 1962 drama “The Interns.”

Despite his continued work in films, Robertson failed to reach the top level of stardom — or, as he put it in the early 1960s, he had yet to make it to “that golden circle of three or five [stars] in Hollywood who can pick and choose” their movie roles.

Robertson appeared to be on his way after President Kennedy personally approved him to star in “PT 109,” the 1963 film about Kennedy’s heroic World War II exploits in the Navy as a motor torpedo boat skipper in the South Pacific.

Although described in a Look magazine cover story as “The Big Epic that Robertson’s career has always needed,” “PT 109” ultimately didn’t do much to advance the screen career of what the magazine called “one of the finest young actors in America today.”

In contrast to most of the movies he was making at the time, the stage and television brought Robertson some of his choicest roles.

On Broadway in 1957, he played the lead role of the drifter in Tennessee Williams’ “Orpheus Descending,” the same role Marlon Brando played in “The Fugitive Kind,” director Sidney Lumet’s 1959 movie version of the play.

And on television, he played an alcoholic in the critically acclaimed 1958 “Playhouse 90” production of “The Days of Wine and Roses,” only to see Jack Lemmon land the role in the 1962 movie version.

Frustrated by seeing roles he originated go to major movie stars for the film versions — “I had a reputation then for being the bridesmaid, never the bride” — Robertson wasn’t about to let it happen again when he starred in the 1961 production of “The Two Worlds of Charlie Gordon” on “The United States Steel Hour.”

While still in rehearsals for the TV role that would earn him an Emmy nomination, Robertson bought the movie rights to the story of a mentally disabled man who undergoes an experimental brain operation that increases his IQ but later discovers that the life-altering changes won’t be permanent.

Robertson continued to appear in films, notably playing a ruthless, conservative presidential candidate in “The Best Man,” a 1964 drama co-starring Henry Fonda. In the meantime, he continued to do research for the title role in what became the movie “Charly.”

“I would visit shelter workshops,” he recalled in a 2006 interview with The Times. “I spent a lot of time with retarded people on both coasts.”

In his review of the film, Chicago Sun-Times critic Roger Ebert expressed displeasure with “the whole scientific hocus-pocus” aspect of it. But he called it “a warm and rewarding film” and described Robertson’s portrayal of the good-natured Charly, who post-operatively falls in love with his teacher (played by Claire Bloom), as “a sensitive, believable one.”

In the wake of his Oscar win, Robertson was a star in films such as “The Great Northfield Minnesota Raid,” “Man on a Swing,” “Three Days of the Condor” and “Obsession.”

He also starred in, produced, co-wrote and directed “J.W. Coop,” a 1972 drama about an ex-con who returns to his life as a professional rodeo cowboy, as well as starring in a number of TV movies and the mini-series “Washington: Behind Closed Doors.”

But in 1977, Robertson’s life took an unexpected twist after he received an IRS form for “miscellaneous income” that indicated that Columbia Pictures had paid him $10,000 the previous year.

Robertson, however, hadn’t done any work for Columbia that year and had not received $10,000 from the studio.

After asking his accountant to look into it, Robertson learned that a check for $10,000 had been made out to him and had been cashed at a bank in Beverly Hills. The endorsed check, bearing Robertson’s forged signature, had been processed and paid out in American Express travelers’ checks to the president of Columbia Studios, David Begelman.

After consulting his attorney, Robertson notified the local police. But after months of inactivity, he took the advice of Arizona congressman Morris K. Udall, whom he had supported in the 1976 Democratic presidential primaries, and contacted the FBI.

“I was simply looking out for No. 1,” Robertson told People magazine in 1983. “I wasn’t trying to be Don Quixote. If I hadn’t done what the law required, which was to give evidence to the authorities, I would have been a party to a crime.”

The ensuing Begelman embezzlement scandal, which came to symbolize Hollywood corruption, was chronicled in David McClintick’s 1982 bestseller “Indecent Exposure: A True Story of Hollywood and Wall Street.”

In March 1978, Begelman was charged with grand theft and three counts of forgery: for forging the names of Robertson, director Martin Ritt and restaurateur Pierre Groleau on checks written in the amounts of $10,000, $5,000 and $25,000 respectively.

Three months later, Begelman was fined $5,000 and placed on three years’ probation. The judge, who directed Begelman to continue the psychiatric treatment he had recently begun, also accepted Begelman’s offer to make a documentary on the dangers of “angel dust” (PCP) as a public service.

Begelman, whose grand-theft conviction was reduced from a felony to a misdemeanor in 1979, was hired later that year to head MGM’s motion picture division, and he later became a producer. He committed suicide in 1995.

For his part in exposing the embezzlement, Robertson said, he was blackballed in Hollywood for 3 1/2 years.

“I broke the unwritten commandment: Thou shalt never confront a major mogul on corruption,” he told The Times in 1998. “Suddenly, the phone stopped ringing.”

Robertson said his Hollywood exile ended in 1981 when director Douglas Trumbull cast him in a role in “Brainstorm,” a thriller released in 1983 starring Christopher Walken and Natalie Wood.

Robertson later appeared with Jacqueline Bisset and Rob Lowe in the comedy-drama “Class,” played Hugh Hefner in Bob Fosse’s “Star 80” and joined the cast of TV’s “Falcon Crest.” He also launched a long run as the commercial spokesman for AT&T.

The son of the heir to a ranching fortune, he was born Clifford Parker Robertson III on Sept. 9, 1923, in Los Angeles.

His parents were divorced when he was 2 and his mother died of a ruptured appendix several months later. He grew up in the La Jolla home of his maternal grandmother, a divorcee who adopted him.

A lifelong aviation enthusiast who had a collection of vintage aircraft, Robertson began learning to fly at 14.

After graduating from high school, Robertson spent World War II in the Merchant Marine. After the war, he attended Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio, and worked briefly as a reporter for a daily newspaper in Springfield, Ohio.

With thoughts of becoming a playwright, he moved to New York City, where he was advised that the best way to learn about the theater was to get a job in summer stock.

In the early 1950s, Robertson began landing parts in live television anthology series such as “Armstrong Circle Theatre” and “Hallmark Hall of Fame.” He also starred in the title role of “Rod Brown of the Rocket Rangers,” a live Saturday morning TV series on CBS from 1953 to ’54.

In 1957, Robertson married actress Cynthia Stone. The marriage, during which they had a daughter, Stephanie, ended in divorce in 1959. Robertson’s 1966 marriage to actress Dina Merrill ended in divorce in 1986. Their daughter, Heather, died of cancer in 2007.

Robertson is survived by his daughter Stephanie Robertson Saunders of Charleston, S.C., and a granddaughter.

PHOTOS: Notable deaths of 2011

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.