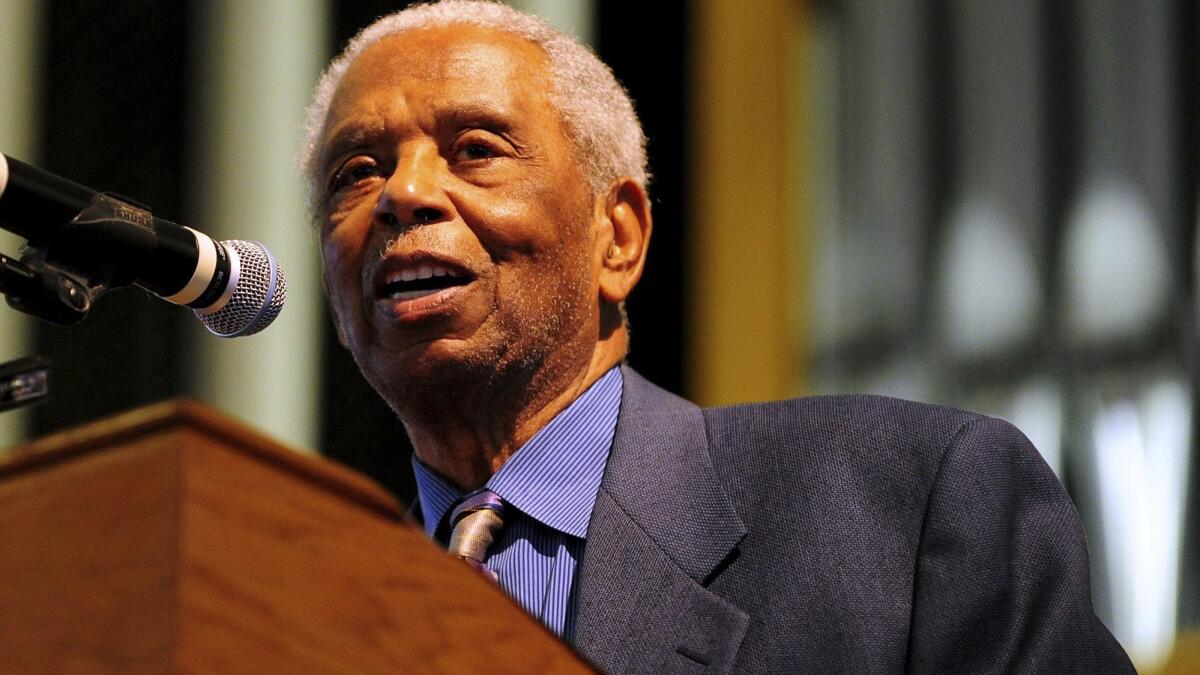

Damon J. Keith, civil rights jurist who ruled against both Nixon and Bush, dies at 96

Reporting from Detroit — Judge Damon J. Keith, a grandson of slaves and a leading figure in the civil rights movement, has died at the age of 96. As a federal judge, Keith was sued by President Richard Nixon over a ruling against warrantless wiretaps.

Keith died in his hometown of Detroit, the city where the prominent lawyer was appointed in 1967 to the U.S. District Court.

Keith served more than 50 years in the federal courts. Before his death, he still heard cases about four times a year at the 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Cincinnati.

A revered figure in Detroit for years, Keith captured the nation’s attention with the wiretapping case against Nixon and Atty. Gen. John Mitchell in 1971. Keith said the government could not engage in the warrantless wiretapping of three people suspected of conspiring to destroy government property. The decision was affirmed by the appellate court, and the Nixon administration appealed and sued Keith personally. The case went all the way to the Supreme Court, where the judge prevailed in what became known as “the Keith case.”

Keith revisited the civil liberties theme roughly 30 years later in an opinion that said President George W. Bush could not conduct secret deportation hearings of terrorism suspects. Keith’s opinion contained the line, “Democracies die behind closed doors.”

“During his more than 50 years on the federal bench, he handed down rulings that have safeguarded some of our most important and cherished civil liberties, stopping illegal government wiretaps and secret deportation hearings, as well as ending racial segregation in Pontiac [Mich.] schools,” Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan said in a statement.

Praveen Madhiraju, Keith’s former law clerk who worked with him on the 2002 opinion against Bush, was credited with coining the “Democracies die behind closed doors” line, but the attorney, now based in Washington, D.C., said Keith deserved far more credit.

“I came up with the words, but Judge Keith was clearly the inspiration behind the whole thing,” Madhiraju said in 2017. “There’s no way if I’d worked with any other judge in the country I would have thought of that phrase.”

Madhiraju said it helped that Keith would periodically pop into the clerk’s office to offer suggestions, such as instructing him to review the Pentagon Papers on U.S. policy toward Vietnam and the words of the late Sen. J. William Fulbright, who said, “In a democracy, dissent is an act of faith.”

In a 2017 interview, Keith said that the phrase “Equal justice under law” etched onto the U.S. Supreme Court building in Washington inspired him and always summoned the lessons Thurgood Marshall taught him as one of his professors at Howard University. Marshall became the first black Supreme Court justice in October 1967 — the same month Keith received his federal appointment.

He recalled Marshall saying, “The white men wrote those four words. When you leave Howard, I want you to go out and practice law and see what you can do to enforce those four words.”

Keith did just that. In 1970, he ordered a bus policy and new boundaries in the Pontiac, Mich., school district to break up racial segregation. A year later, he made another groundbreaking decision, finding that Hamtramck, Mich., illegally destroyed black neighborhoods in the name of urban renewal with the federal government’s help. The remedy was 200 housing units for blacks. The court case is still alive decades later due to disputes over property taxes and the slow pace of construction.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.