Henry Segerstrom, O.C. developer and philanthropist, dies at 91

Henry T. Segerstrom, the courtly real estate developer and arts philanthropist who was instrumental in transforming Orange County from a provincial bedroom community into a nexus of culture and commerce, has died. He was 91.

Segerstrom died Friday at his home in Newport Beach after a brief illness, according to Debra Gunn Downing, a spokeswoman for South Coast Plaza.

Segerstrom transformed his family’s agricultural fields in Costa Mesa into South Coast Plaza, which opened with 78 stores in 1967 in a sleepy, largely undeveloped area.

Segerstrom saw the county’s wealth growing, and with it, an appetite for expensive things. Over the years, personally courting high-end retailers such as Barney’s New York, Armani and Chanel, he oversaw the shopping center’s transformation into one of the nation’s premier retail complexes.

“He saw retailers throughout the world he thought should be here, and he called on them personally and in a lot of cases was successful,” said Thomas Nielsen, a civic leader and longtime Segerstrom friend.

With about 280 stores, $1.7 billion in annual sales and more than 22 million visitors a year, it boasts of being “the highest-grossing planned retail center in the United States.”

Despite his success as a businessman and philanthropist, Segerstrom would for his whole life introduce himself as a farmer. The grandson of family patriarch C.J. Segerstrom, and the scion of the nation’s largest independent lima bean producer, Segerstrom was born in Santa Ana on April 5, 1923.

He attended Santa Ana High School, where he was senior class president. He joined the Army as a private at age 19, attended Officer Candidate School and fought with a field artillery unit during World War II. In France, during the Battle of the Bulge, he suffered a serious shrapnel wound that subjected him to multiple surgeries in a military hospital and left his right hand permanently maimed.

After leaving military service as a captain, he attended Stanford University, where he received a bachelor’s degree and an MBA. Soon he was part of C.J. Segerstrom & Sons, a family business focused on agriculture.

“There was no indication when I joined the firm that we were going to do anything differently,” Segerstrom once said in an interview. But the family soon expanded beyond farming with the purchase of surplus property from the shuttered Santa Ana Army Air Base.

With its farming roots, Costa Mesa had once been called “Goat Hill,” a term long trotted out with derision as it labored in the shadow of affluent Newport Beach. From the start, Segerstrom believed the city’s South Coast Plaza area was destined to become “the downtown” of Orange County, a promise that invited skepticism. In 1975, when Segerstrom opened a luxury 17-story hotel amid the bean fields, some predicted it would be “Segerstrom’s Waterloo,” though it soon proved a magnet for out-of-town professionals.

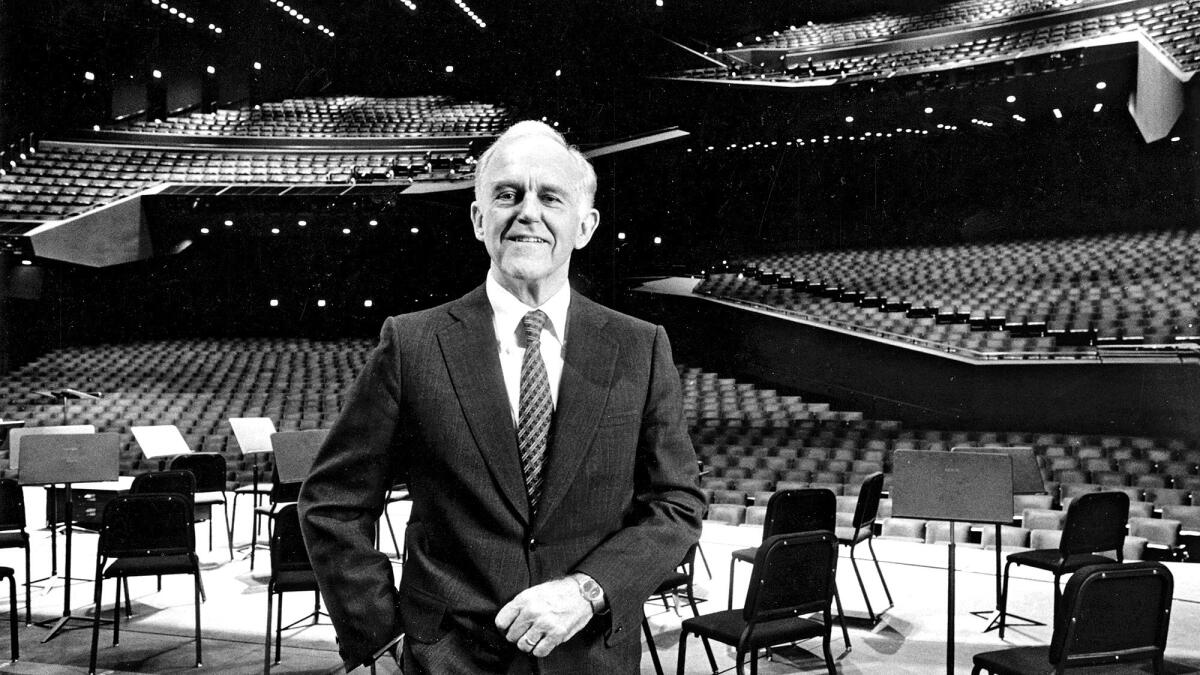

But Segerstrom had larger plans still. In 1979, his family donated five acres of land and at least $6 million to build the Orange County Performing Arts Center in Costa Mesa, which opened seven years later across the street from South Coast Plaza. Many consider the construction of the complex, which was renamed in 2011 to honor Segerstrom, a pivotal point for the arts in Orange County. Segerstrom, the center’s founding chairman, was characteristically involved, even traveling to Sweden to select the granite for the building.

“There was very little knowledge or understanding of how deep a classical culture or even popular culture complex would be supported by the population base of Orange County,” Segerstrom said.

Segerstrom’s vision won him a reputation as a pioneer of the national boom in urban-village complexes — so-called edge cities that combine business and entertainment, retail outlets and housing near metropolitan areas.

“I grew up here, and as far as I’m concerned culture came to Orange County when we created the arts center,” Nielsen said. “I can’t imagine there were any other people that would have made the scale of difference that he has.”

In an economic study he conducted of South Coast Plaza nearly 30 years ago, James L. Doti, president of Chapman University in Orange, said he found the shopping center was even then drawing people from Los Angeles and the Inland Empire, a harbinger of the seismic impact it would have in the following decades.

“At a time when Orange County was still considered a bedroom community to Los Angeles, that was the first sign that it was becoming its own separate geographic center,” Doti said.

For years, Segerstrom weathered criticism that his cultural largesse had the aim of enriching his business interests, but he called his arts patronage “personal and sincere.” Segerstrom’s Newport Beach mansion on the Balboa Peninsula featured world-class artwork, including pieces by Henry Moore, Milton Avery and Henri Matisse.

Famous for wooing artists, donors and business partners, Segerstrom occasionally made a gift of Hermes bags containing lima beans, in a nod to his beginnings as a farm boy. He doggedly pursued Japanese artist Isamu Noguchi, who initially rebuffed him but went on to create “California Scenario,” a six-piece sculpture garden, for an office courtyard in 1982. Among the artwork was a 28-ton granite sculpture featuring an abstract arrangement of precision-cut boulders called “The Spirit of the Lima Bean,” in homage to the land’s — and the patron’s — history.

At the Performing Arts Center, Segerstrom commissioned world-famous sculptors such as Richard Serra to create outdoor works, and spearheaded the center’s expansion, culminating in the September 2006 opening of the 2,000-seat, $200-million Renee and Henry Segerstrom Concert Hall across the street from the original hall. Segerstrom donated the land and $50 million, and handpicked Cesar Pelli as the architect.

Doti said that the arts center, beyond its cultural contributions, had generated significant jobs and allowed other nonprofit organizations, including Opera Pacific, to flourish.

“His vision, his tenacity, has really made the Performing Arts Center a reality. Without his leadership, it wouldn’t exist,” Doti said.

The business headquarters of C.J. Segerstrom & Sons faces remains of the family’s farming operation and the two-story farmhouse that Segerstrom’s grandfather built in 1915.

For 31 years, Segerstrom was married to his first wife, Yvonne, with whom he had two sons, Toren and Anton, and a daughter, Andrea. Months after their divorce in 1981, he married his second wife, Renee, who became one of Orange County’s most successful arts fundraisers. The marriage lasted nearly 20 years, until her death in 2000 at age 72.

Soon after, a daughter she had disowned, Mikette Von Issenberg, sued Segerstrom demanding a portion of her late mother’s fortune and claiming Segerstrom was holding it hostage. The case settled quietly. It was a rare public spat for Segerstrom, who had a reputation for decorum and for guarding his family’s privacy. In conversation with reporters, he was at times voluble about his philanthropic projects but unfailingly guarded about his personal life.

A month after Renee Segerstrom’s death, Segerstrom, then 77, married his third wife, Elizabeth Macavoy, a 45-year-old clinical psychologist. Segerstrom and his new bride said they met just three weeks before their wedding while dining separately in the same New York restaurant.

Segerstrom said he introduced himself to her as a farmer.

In addition to his wife, Segerstrom is survived by his three children, six grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren.

A public visitation and tribute will be held at Fairhaven Memorial Park in Santa Ana on Feb. 28.

christopher.goffard@latimes.com

Times staff writer Mike Boehm contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.