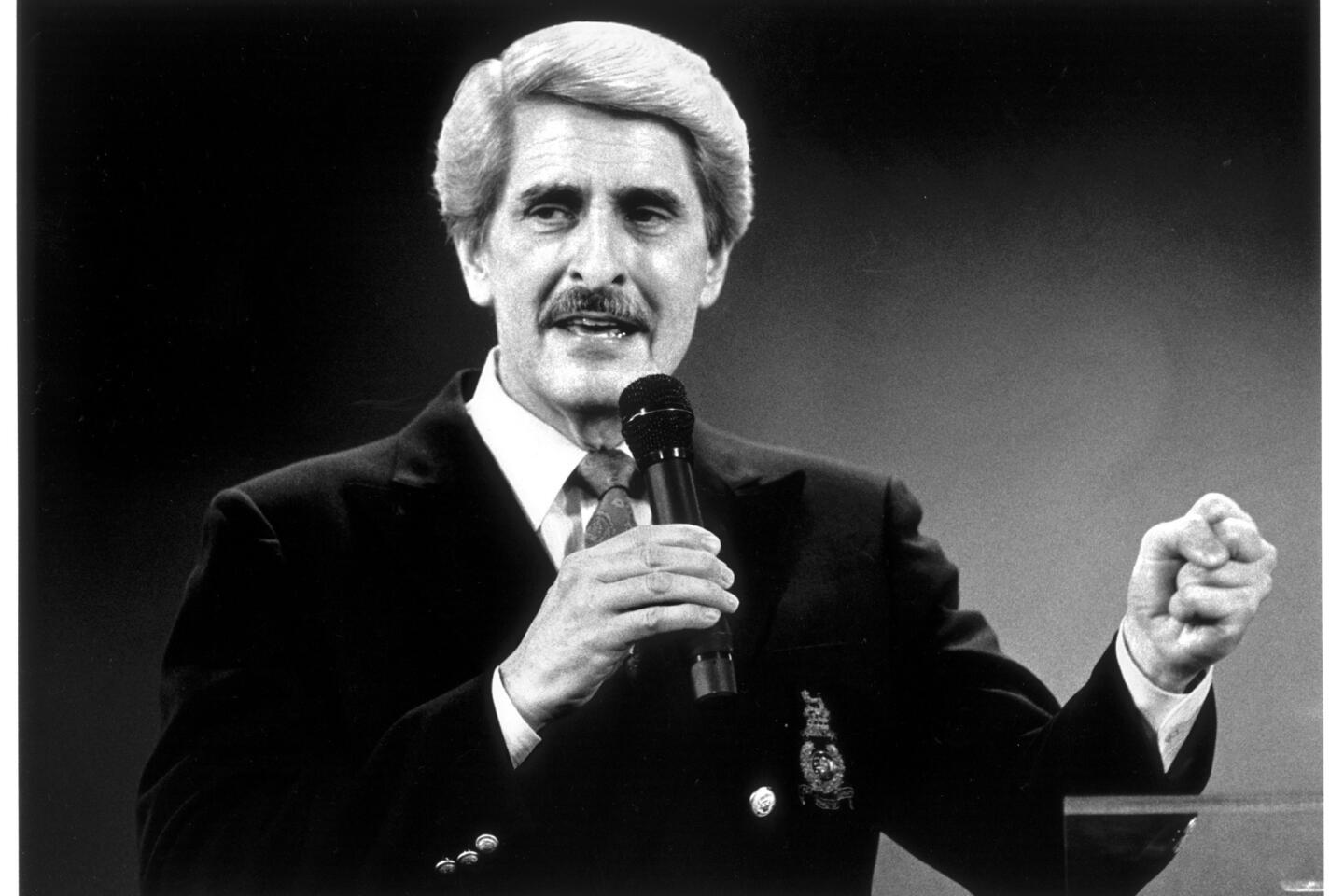

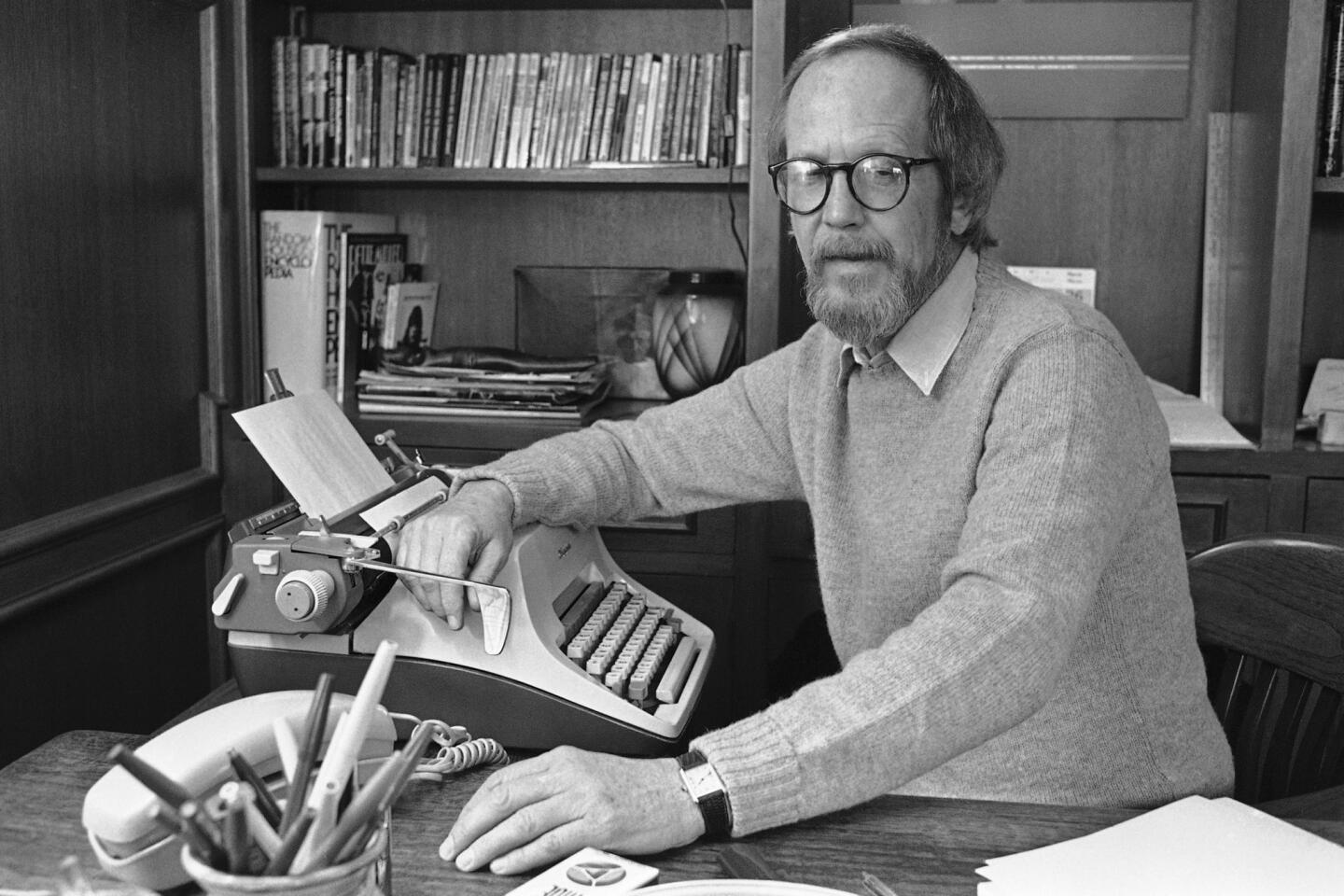

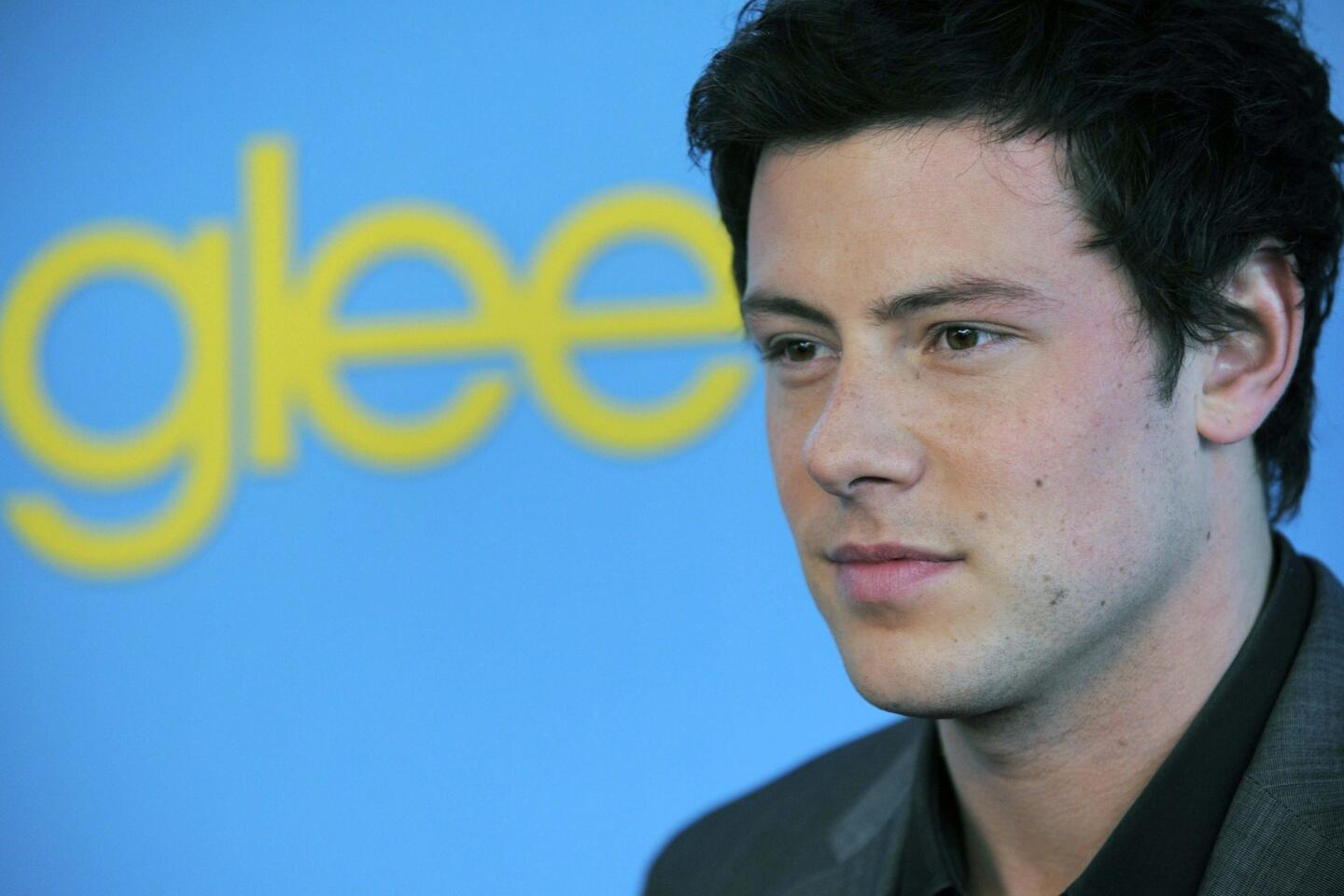

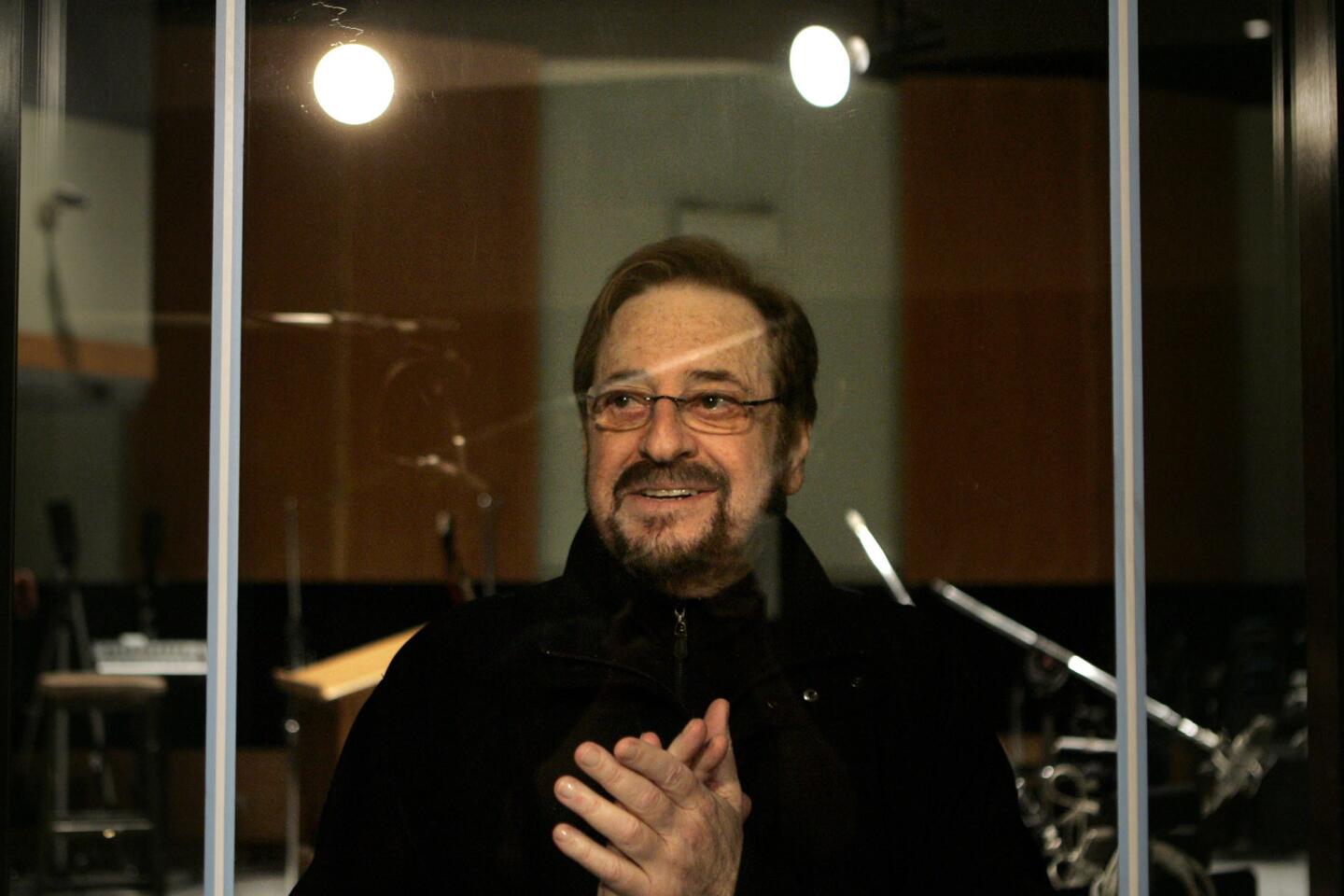

Leonard Kerpelman dies at 88; lawyer in landmark school prayer case

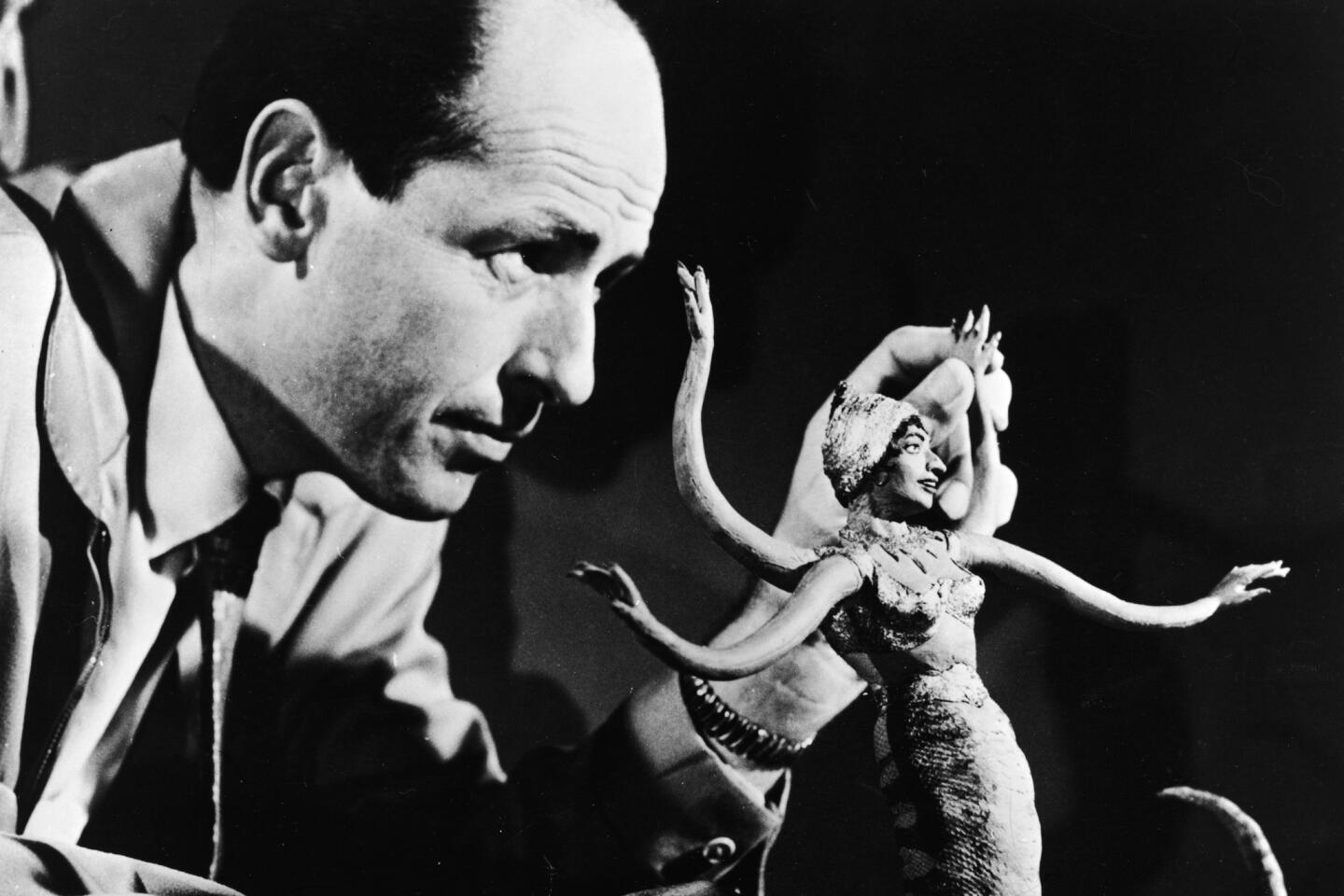

Activist attorney Leonard J. Kerpelman, best known for representing atheist Madalyn Murray O’Hair in the landmark 1963 Supreme Court case that outlawed prayer in public schools, died Thursday at a Baltimore hospital of complications from a tumor. He was 88.

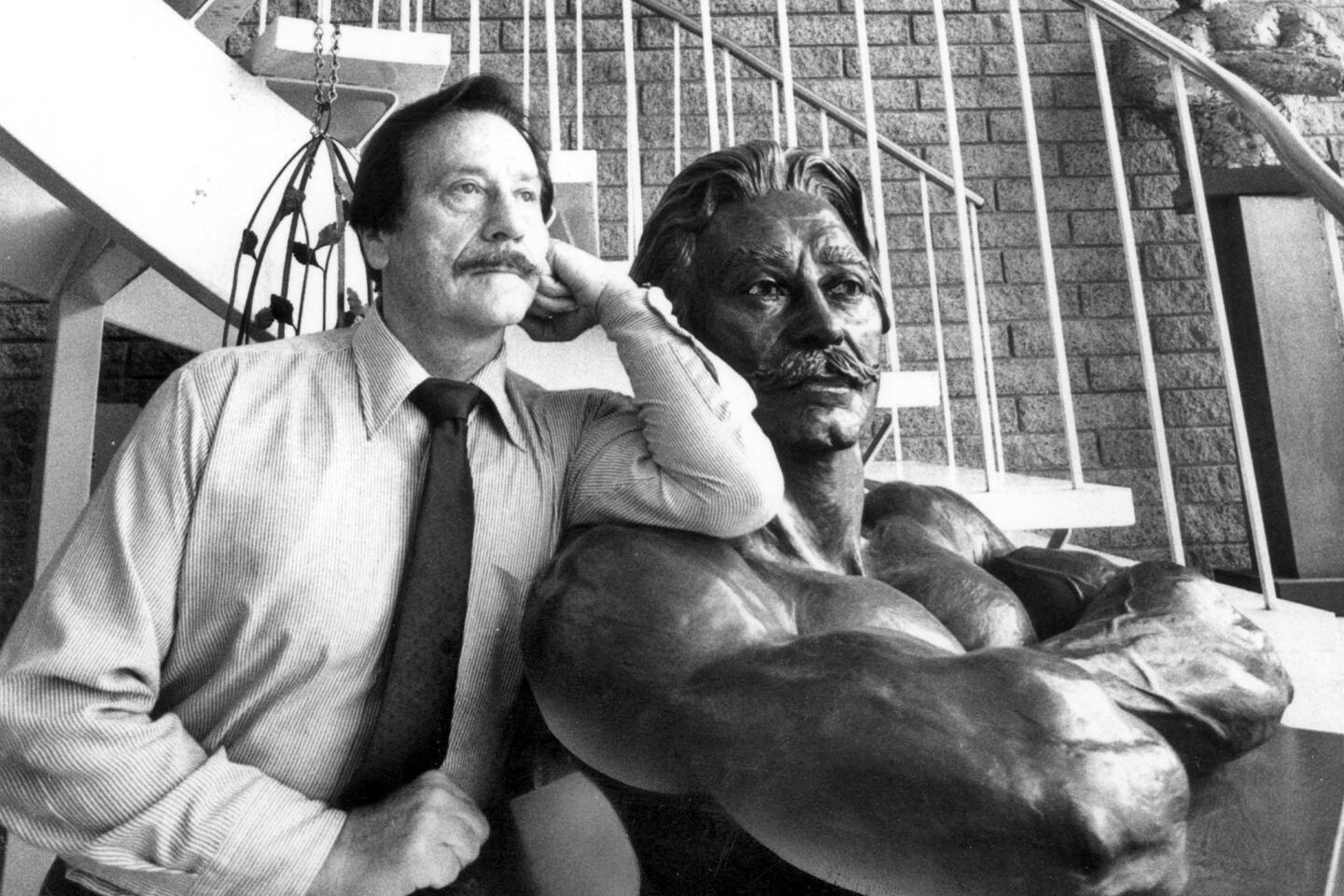

He took on numerous often unpopular causes during his long career that ended in disbarment in 1989, in part for disrupting a judicial hearing. And he was known as a colorful figure in Baltimore, driving a 1948 Cadillac and at times jumping into public fountains.

“It’s always good to have a person who speaks out on a variety of issues like Leonard,” said J. Joseph Curran Jr., former Maryland attorney general. “He took on unpopular causes but was not an unpopular person.”

Leonard Jules Kerpelman, the son of attorneys, was born in 1925 in Baltimore. He suffered from polio as a child and was blind in one eye. He earned a bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering in 1945 from Johns Hopkins University and a law degree in 1949 from the University of Maryland.

From the beginning, he had a flair for taking on high-profile cases. By 1957, he was earning headlines when he represented a Colombian promoter who wanted to bring bullfighting to Baltimore.

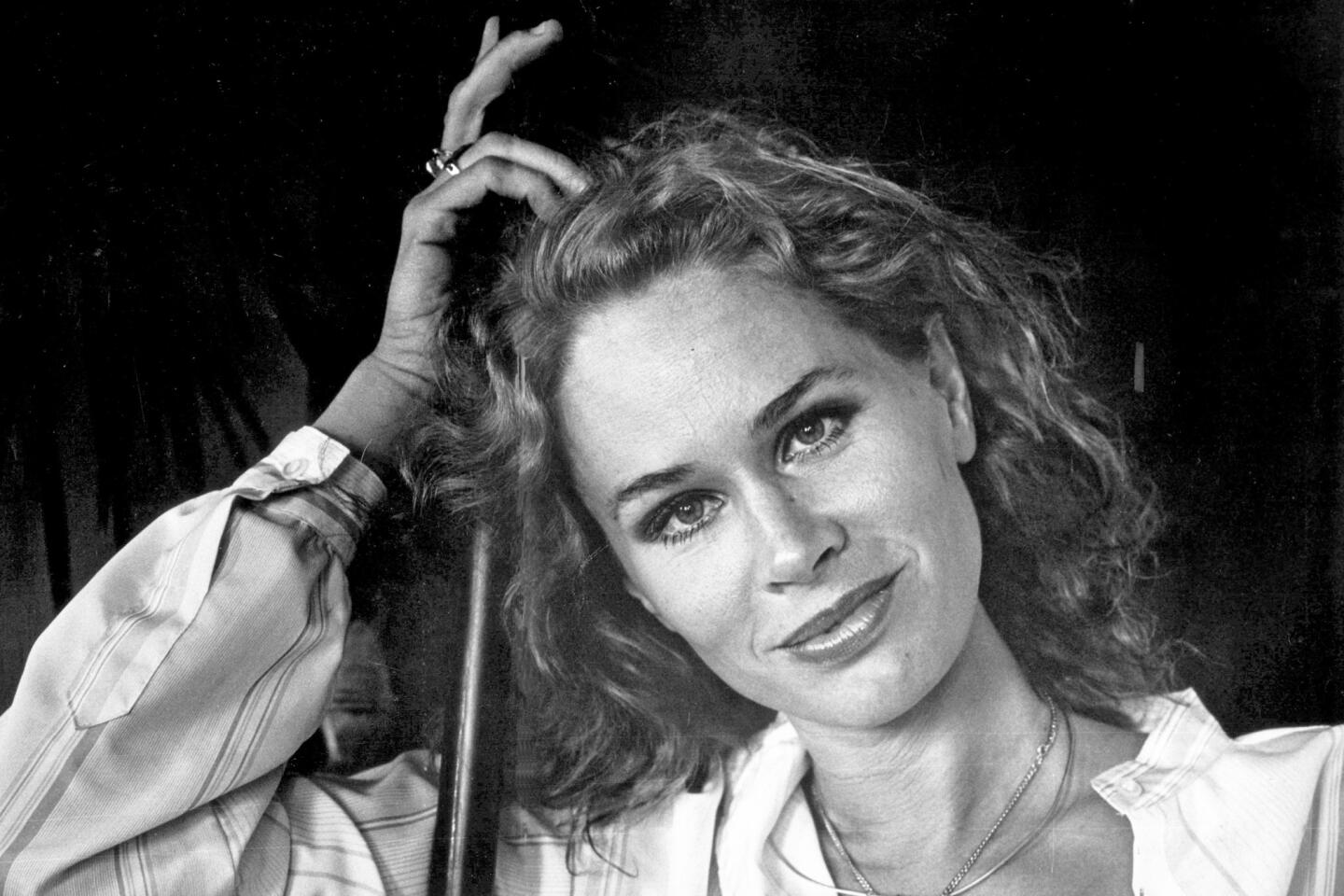

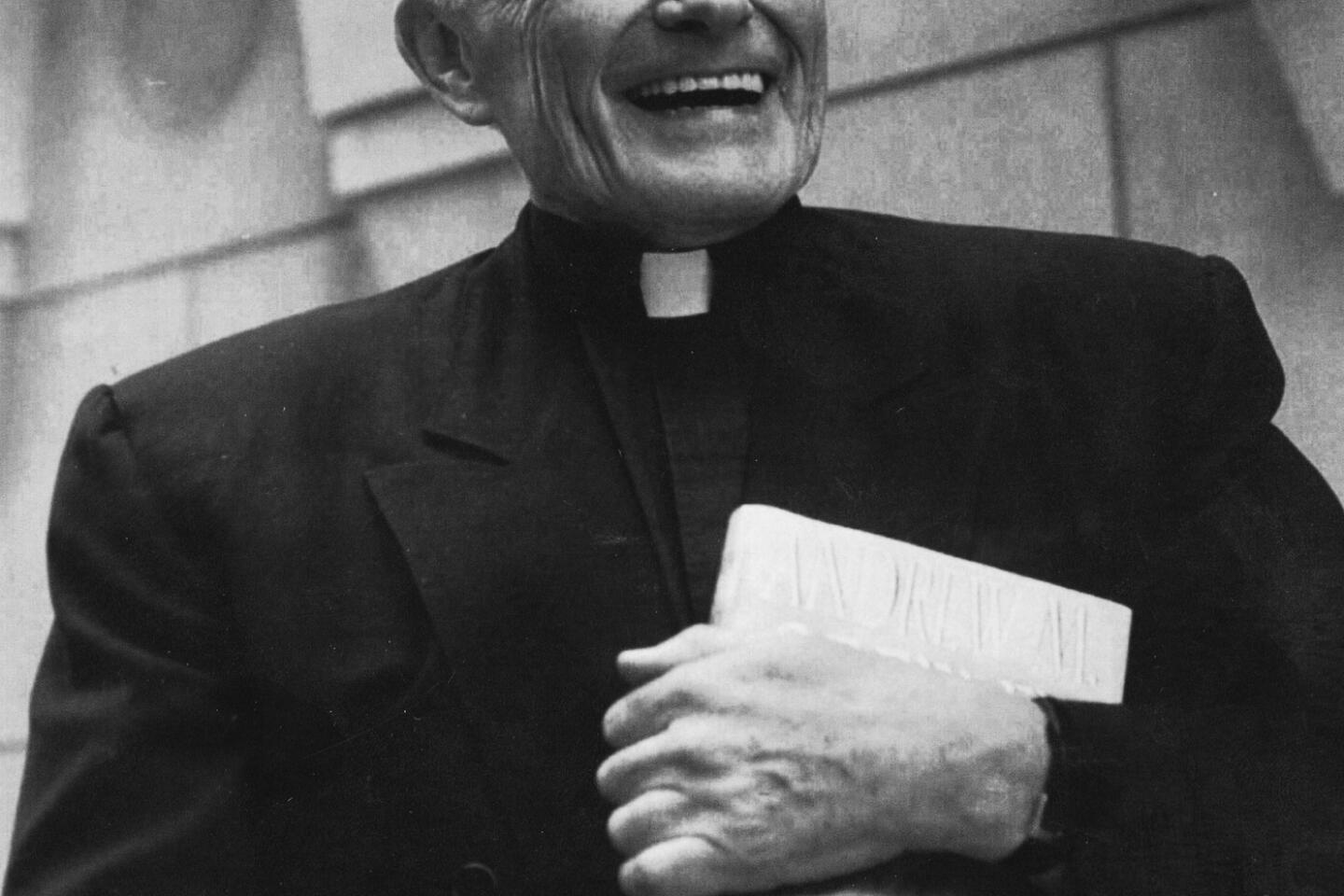

The case that brought him lasting fame revolved around O’Hair, who was opposed to prayer in public school classrooms and stated she was going to keep her son home until the prayers stopped.

“I see no constitutional objection to the study of religion, history of religion, or the study of the Bible as literature,” Kerpelman said in a Sun interview in 1963. “But this ceremony is sectarian, and it is impossible to have such a ceremony that is not sectarian.”

He took the case to the Supreme Court, winning an 8-1 decision.

The outcome brought on waves of hate mail and other forms for criticism, which Kerpelman seemed to relish. In a letter published in the Washington Post, he wrote: “Those whose letters contained threats of physical violence: Please contact my secretary for an appointment. There is a considerable waiting list.”

O’Hair left Baltimore in 1964, according to the Washington Post. In 1995, she disappeared, along with her son and granddaughter. Their remains were found in 2001 buried on a ranch in Texas, and O’Hair’s former office manager admitted to the slaying.

Kerpelman stirred up more controversy in 1965 when he quit as a member of the National Assn. for the Advancement of Colored People after the Watts riots. Though an outspoken supporter of civil rights, he said in a letter to the Sun that he objected to “the manner in which Negro leaders have drawn the Watts carnage to their bosom and have declared it to be, not their shame, but their glory.”

The president of the NAACP in Maryland, Juanita Jackson Mitchell, called his stance “ridiculous,” in an Associated Press report. “No one in his right mind hugs bloodshed and killing to one’s bosom whether it is in Watts or in Vietnam,” she said. But Kerpelman never rejoined the organization.

Kerpelman went on to establish Fathers United for Equal Rights, a men’s rights group that sought equal treatment for men in custody and divorce litigation, and he took on cases concerning environmental and preservation issues in the city he loved. In 1967 he was spotted wading in a new public fountain. He told a reporter, “Beauty must be celebrated, and this fountain is magnificent.”

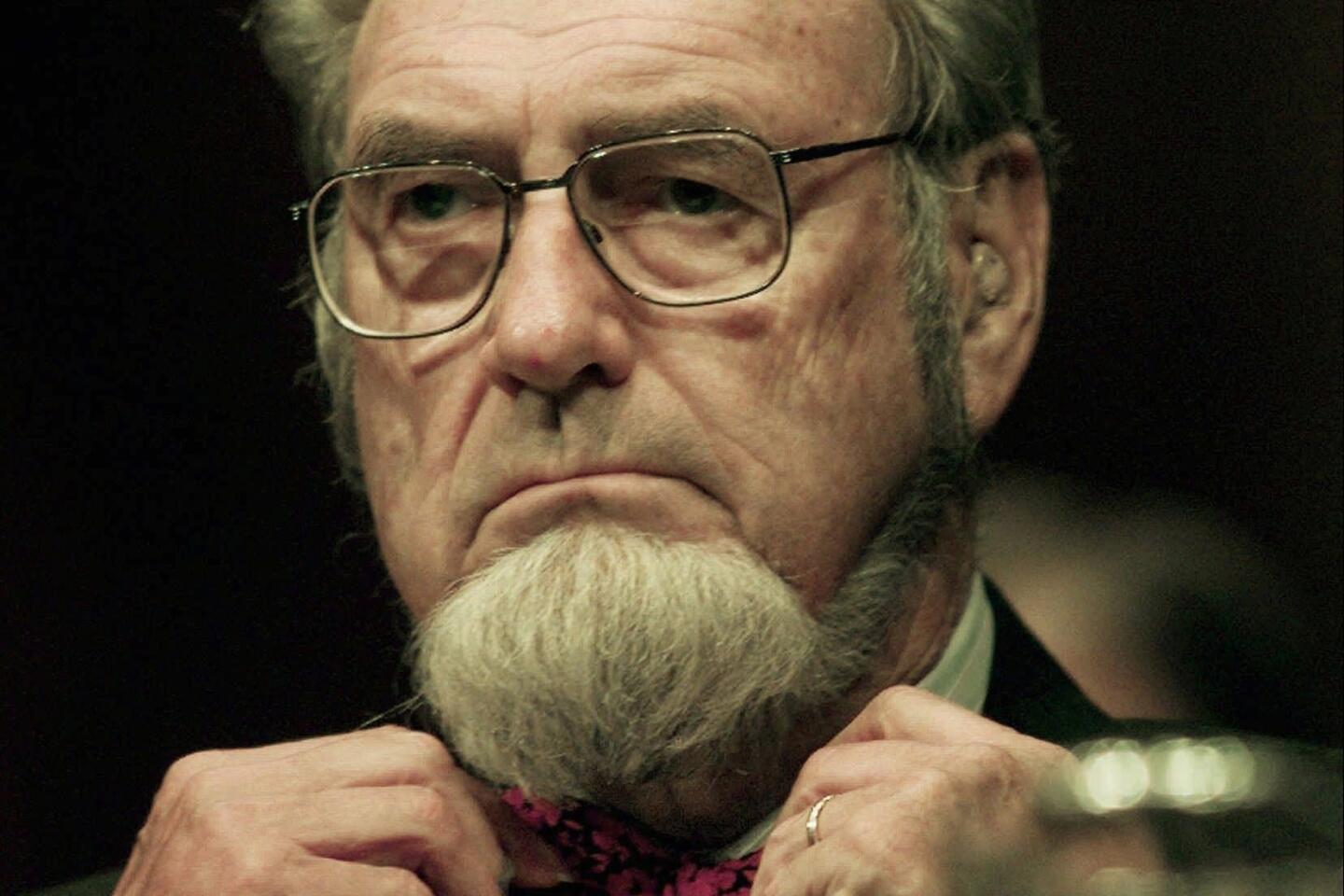

He was disbarred in 1989 after the Maryland Court of Appeals ruled that he disrupted a proceeding and also charged an excessive fee in a case. He later took to spending days in City Hall, shooting videos of meetings that were aired on cable TV stations.

His daughter, Antonia Fowler, said he lived to stir up the complacent. “My father loved and stood up for his country and the intent of the Constitution of the United States from the start of his career until the end of his days,” she said.

He is survived by his wife of 63 years, the former Elinor Hoffman, retired deputy director of the Maryland State Human Relations Commission; two sons, two daughters, three brothers, a sister and eight grandchildren.

Rasmussen writes for the Baltimore Sun. Baltimore Sun researcher Paul McCardell contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.