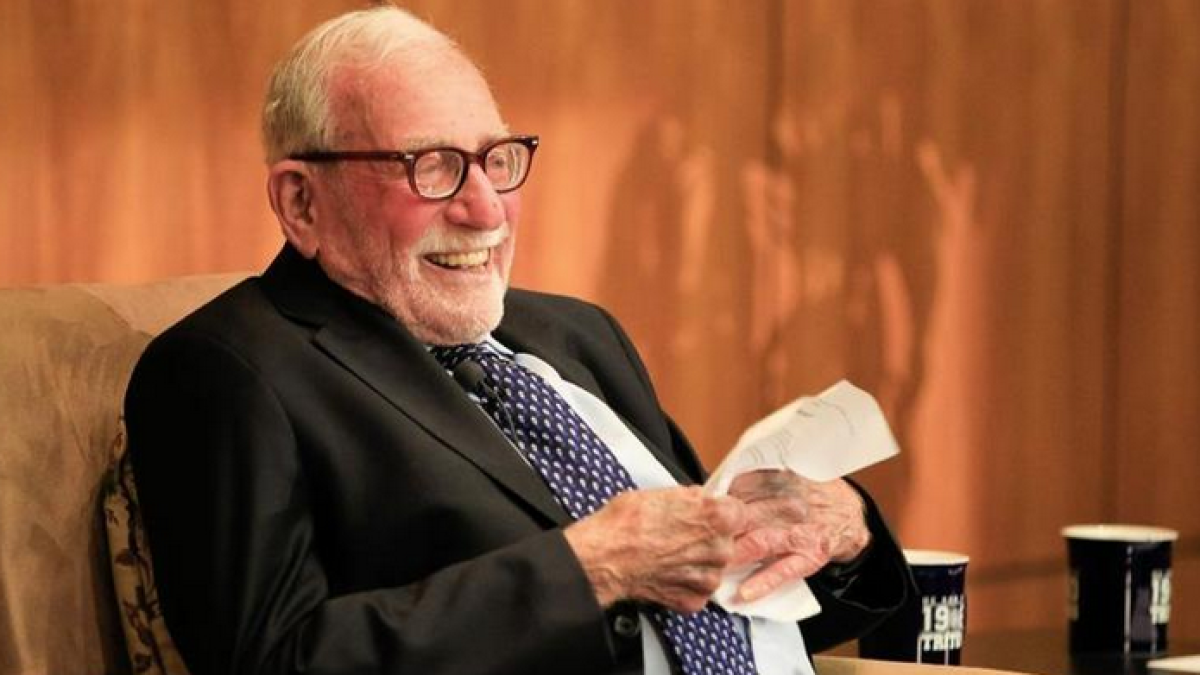

Walter Munk, La Jolla scientist-explorer dubbed the ‘Einstein of the Oceans,’ dies at 101

Walter Munk, the high-spirited scientist-explorer whose insights about the nature of winds, waves and currents earned him the nickname the “Einstein of the Oceans,” died Friday in La Jolla. He was 101.

Munk died of pneumonia at Seiche, his seaside home near UC San Diego, a campus he helped make famous through decades of work at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

His death was announced by his wife, Mary Munk, who told the San Diego Union-Tribune, “We thought he would live forever. His legacy will be his passion for the ocean, which was endless.”

Munk was a raspy-voiced barnacle of a man, always in and around water, trying to figure out how waves broke, where currents moved, and why changes in the ocean’s makeup affected Earth’s climate.

He greatly improved surf forecasting, helping countless American troops land more safely during the D-Day invasion in World War II. He also helped analyze the impact of a hydrogen bomb blast in the early 1950s by standing on a tiny raft miles away, where he got showered with radioactive fallout.

And he was among the first wave of scientists to pull on scuba gear and explore wondrous and wicked oceans.

Munk also was endlessly curious about marine life, especially fish — and he eventually had a delightfully weird one named after him. It was a species of devil ray that has an extraordinarily ability to leap out of the water, giving the impression that it can fly.

He went in search of the devil ray a few years ago during a trip that was filmed for a documentary. The film shows Munk in a familiar setting, standing at the rail of the boat, the wind ruffling his whitish-gray locks as he stared into the sea in joy and amazement.

“Walter was the most brilliant scientist I have ever known,” said Pradeep Khosla, UC San Diego’s chancellor.

“I stand in awe at the impact [he] had on UC San Diego, from his countless discoveries that put the university on the map as a great research institution, to his global leadership on the great scientific issues of our time.”

Margaret Leinen, director of Scripps Oceanography, said, “Walter Munk has been a world treasure for ocean science and geophysics.

“He has been a guiding force, a stimulating force, a provocative force in science for 80 years. While one of the most distinguished and honored scientists in the world, Walter never rested on his accomplishments. He was always interested in sparking a discussion about what’s coming next.”

Few who knew him when he was a youngster would have guessed that his life would turn out that way.

Munk was born on Oct. 19, 1917, and grew up in Austria, where he shrugged off studies during his high school years to indulge his great passion — skiing.

His parents later sent him to Columbia University, hoping that he’d straighten out. He did, but in his own way. He immersed himself in studying — when he wasn’t running the university’s ski club.

Munk’s attention drifted to the West Coast. He fell in love with Pasadena and came to a turning point.

“My mother gave me a tidy amount of money and said, ‘Do what you want,’” Munk said in a 2016 interview.

“I bought a DeSoto convertible, drove to Pasadena and showed up at Caltech. The dean said, ‘Let me pull your file.’ I said there was no file. I was so naive I thought you could go to college wherever you wanted.

“I was told that I could take an entrance exam in a month. I took a room at the corner of Lake and California and, for the first time in my life, really began studying. By some miracle, I passed the exam and became a student at Caltech.”

He later became smitten with a girl and followed her to La Jolla, where he developed the deepest passion of his life, the sea.

Shortly before World War II, he became a graduate student at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, where he began studying surf forecasting. He was soon working for the Navy at a research lab on Point Loma, studying anti-submarine warfare and wave prediction.

He refined those predictions, work that Allied forces widely used in World War II to put troops ashore. Munk’s research later helped other scientists do everything from find better ways to guide ships in the open sea to tell weekend surfers exactly where the waves would break.

His interests multiplied in the 1950s and ’60s. He helped to design grand scientific expeditions to the deep, open ocean, research that helped explain the role of ocean currents and provide a better understanding of why the Earth wobbles on its axis.

In the 1960s, as the U.S. strove to become the first nation to put men on the moon, Munk preferred to look downward, into the sea. He was determined to rally scientists around the idea of drilling into the Earth’s mantle so that they could better understand its composition, evolution and role.

On the whole, this effort, centered around Project MOHOLE, failed. But a test drilling was performed in the early 1960s and scientists learned that they could use acoustic signals from the sea floor to position surface platforms, a major advance in ocean drilling.

This and other work earned him the National Medal of Science, which he received during a White House ceremony.

Munk remained active until quite recently. He and his wife spent most of last summer touring Europe, including a visit to Paris, where he was awarded the French Legion of Honor with the rank of chevalier (knight) for his contributions to oceanography.

“This really means something to me,” a misty-eyed Munk said last fall, sitting at the wooden desk in his home where he would hover over papers with a sharp pencil, noodling out ideas.

He also said he was planning to travel to France this summer for the 75th anniversary of the D-Day landings, though his health put that in question. He had been growing weaker and had problems breathing.

In recent years, Munk was showered with praise for the breadth and genius of his long career. The New York Times referred to him as the “Einstein of the Oceans,” a title that turned his face sour.

“Einstein was a great man,” Munk thundered during an interview with the Union-Tribune. “I was never on that level.”

Munk was preceded in death by his first wife, Judith, and a daughter, Lucian, UC San Diego said in a statement.

He is survived by his wife, Mary Coakley Munk, daughters Edie Munk of La Jolla and Kendall Munk of State College, Pa., and three grandsons.

UC San Diego invited those wishing to express condolences to submit messages by email.

gary.robbins@sduniontribune.com

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.