Lynne Westmore Bloom, the artist who surprised Malibu with the ‘Pink Lady’, dies at 81

Night after night, Lynne Westmore Bloom clung to the rocks above the Malibu Canyon tunnel, preparing her canvas.

She chipped at the flecks of old graffiti, pulled away the brittle bushes and sketched out the outline of what would be her gift to L.A. — and the morning commuters who couldn’t possibly miss it through their windshields.

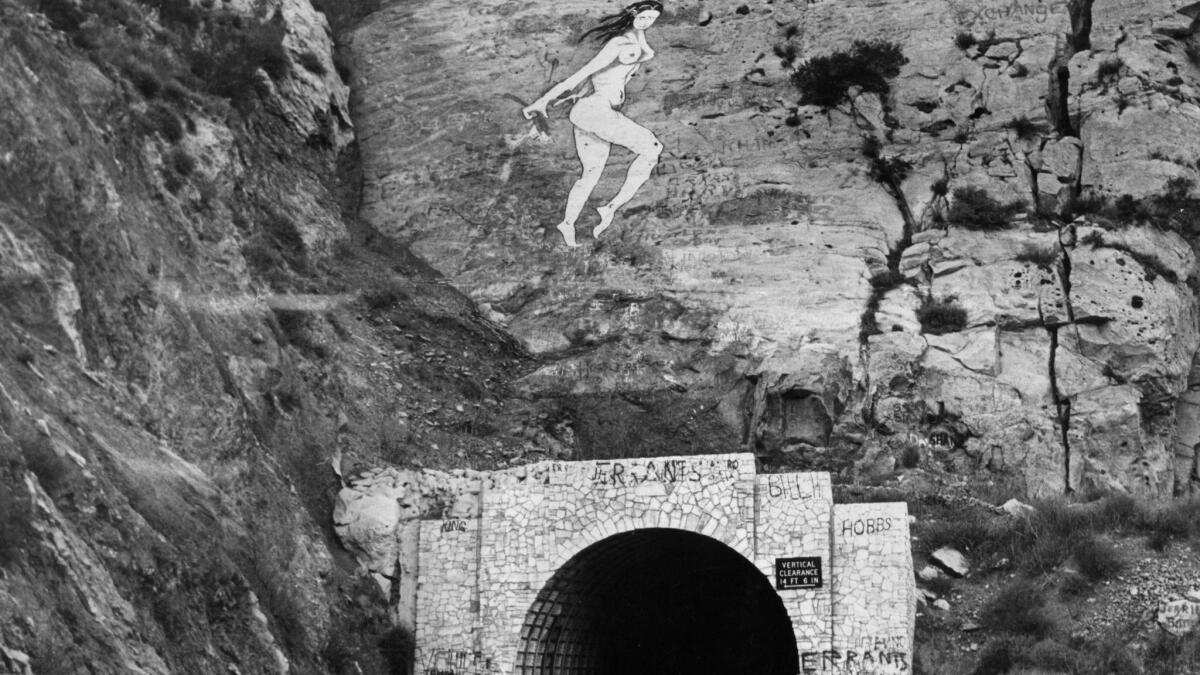

One morning in the fall of 1966, it emerged in full form: a naked lady, 60 feet tall, slightly pink, a fistful of yellow flowers in her right hand and an amused (or frightened, perhaps) look on her face.

Even in a city that had such a healthy appetite for the offbeat and strange, the “Pink Lady of Malibu Canyon” seemed to tower above it all, even if only until county work crews figured out how to cover it up.

City-bound commuters slowed to gawk, drivers pulled to the shoulder to snap pictures, and news crews crawled through the canyon to cover the spectacle. Soon, the “Pink Lady” went as viral as was humanly possible in the pre-social media days.

As work crews wrestled with their task, high-pressure hoses were used to try to blast away the mural, and when that failed, workers mopped paint stripper onto the rock. Finally they hoisted up buckets and covered the “Pink Lady” with brown paint.

“I usually don’t have a feeling that everything I do is precious,” Bloom said in a 1991 interview with The Times. “But in this case, I became its mother, and it became important to me to save her. It was the most ridiculous thing I had ever seen.”

Bloom, who grew up in a family of Hollywood makeup artists and had a long career as a multi-media artist, died Friday in Encinitas, her husband said. She was 81. In addition to her husband, she is survived by son Stephen Seemayer, an independent filmmaker; a grandson and a great-grandson.

William Bloom said his wife initially exalted in the attention showered on the Pink Lady, but later worried it might overshadow her more serious artwork, which was exhibited at the Orlando Gallery in Sherman Oaks, the San Diego Art Institute and at Cal State Northridge.

Bloom said her intention with the “Pink Lady” was not to make a statement or create a highway distraction, but merely give the community a playful alternative to the faded graffiti she found to be an eyesore.

Not everyone agreed. City politicians blasted the mural as an obscenity, and she received both death threats and marriage proposals. And an arts council asked her to judge a painting created by … apes. The attention, she said, eventually cost her a job as a legal secretary.

Bloom later sued the county for $1 million for the loss of her artwork and for invasion of privacy. In turn, the county sued her for the cost of erasing the “Pink Lady.” Both cases were tossed out of court — the county’s after it was determined that the hillside above the tunnel was owned by an individual, not the county.

The notoriety had a positive side too. Galleries suddenly sought her out for showings, a television producer tried to secure rights to her story, and she became a “godmother” in the emerging public art scene in L.A.

A Facebook group still roots for the return of the 60-foot mural, hoping — among other things — that the elements will eventually take a toll on the county’s brown paint and the “Pink Lady” will reappear.

Bloom said she thought about the mural with less frequency as the years passed. But there was one detail that still gnawed at her.

“I was never happy with the mouth,” she said. “There was a rock protruding through the lips, and I thought I could do something about it. If I had more time.”

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.