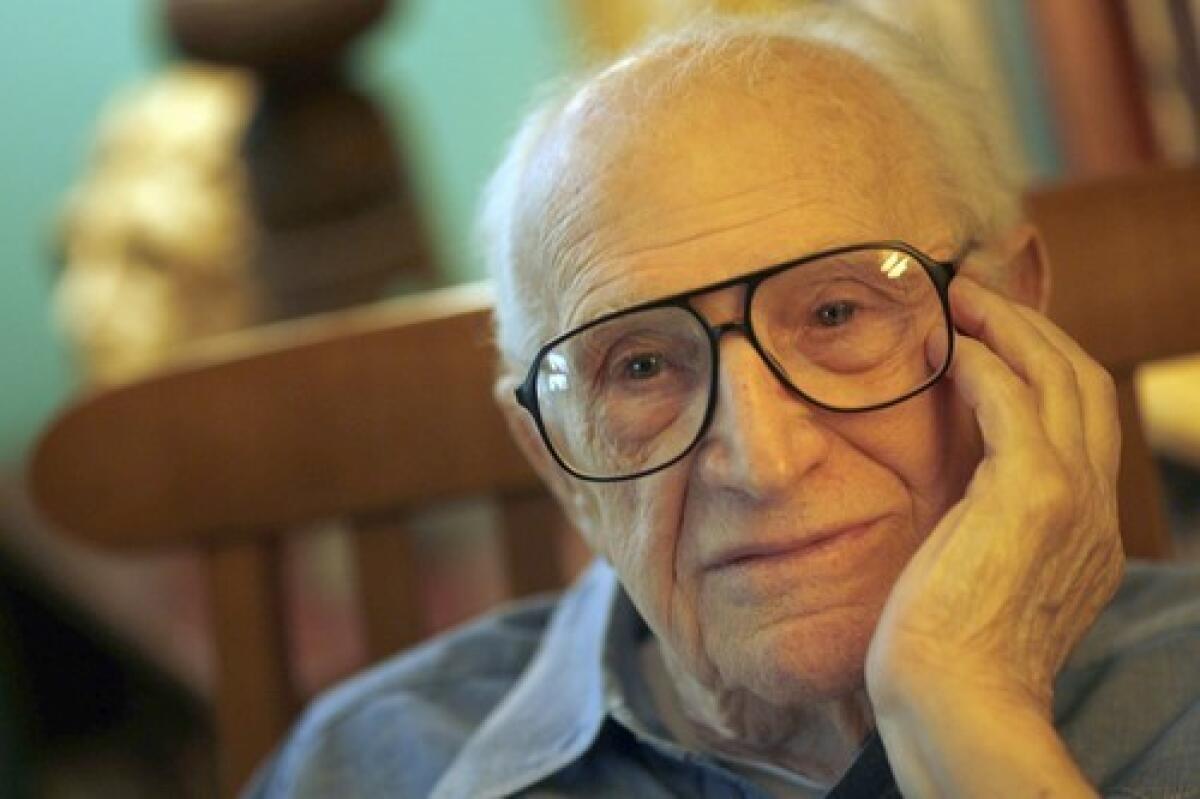

Millard Kaufman, 92, dies; Oscar-nominated screenwriter

- Share via

Millard Kaufman, the Oscar-nominated screenwriter of “Bad Day at Black Rock” and the co-creator of Mr. Magoo who waited until he was 90 to become a first-time novelist, has died. He was 92.

Kaufman died of heart failure Saturday, two days after his birthday, at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, said his son, Frederick Kaufman.

A former newspaperman who launched his screenwriting career after serving in the Marines during World War II, Kaufman quickly made a mark on pop culture by writing the screenplay for “Ragtime Bear,” the 1949 cartoon short directed by John Hubley that introduced the near-sighted Mr. Magoo.

The character, which was voiced by actor Jim Backus, was modeled in part on Kaufman’s uncle.

“My uncle had no problem with his eyes,” Kaufman said in a 2007 National Public Radio interview. “He simply interpreted everything that came across his way in his own particular manner, and he could at times be a little bit difficult, but he would only see things the way they existed highly subjectively to him.”

Kaufman wrote the screenplays for “Unknown World” and “Aladdin and His Lamp” before spending more than a decade as a writer at MGM, where he was known as a top script doctor.

His first screenplay for the studio -- “Take the High Ground!,” a 1953 movie about Army basic training starring Richard Widmark -- earned him the first of his two Oscar nominations.

Then came his Oscar-nominated screenplay for “Bad Day at Black Rock,” the 1955 suspense-drama starring Spencer Tracy as a one-armed World War II veteran who finds more than he bargained for when he gets off the train at a tiny desert whistle-stop.

Other Kaufman film credits are “Raintree County,” “Never So Few,” The War Lord,” “Living Free” and “The Klansman.” Among his TV credits are “Enola Gay: The Men, the Mission, the Atomic Bomb.”

Early in his Hollywood career, Kaufman fronted for blacklisted screenwriter Dalton Trumbo on the 1950 film-noir crime classic “Gun Crazy.”

Kaufman didn’t know Trumbo, but they shared the same agent, George Willner. When Willner asked Kaufman if he’d be willing to put his name on the script, Kaufman later recalled, “I had sense enough to say, ‘Let me talk it over with my wife.’ ”

“But we discussed it and we believed it was rotten that a man couldn’t write under his own name,” Kaufman told Daily Variety in 1992, the year Kaufman officially requested that the Writers Guild of America West take his name off the credits and replace it with Trumbo’s name.

“Any time I had speaking engagements where they included that film in my credits, I always set the record straight anyway,” Kaufman said.

Christopher Knopf, a screen and TV writer who met Kaufman at MGM in the early ‘50s, said that “the greatest facility for him was he was absolutely unafraid to face a blank page with no guarantee of anything.”

“A lot of writers today cannot write unless somebody will call up and say, ‘You have an assignment,’ and that was not Millard; he wrote,” said Knopf.

Kaufman had a major screenwriting assignment at age 86, but then the project fell through.

“I decided, knowing that nobody my age gets work in movies, and that I had to do something, otherwise I’d get into terrible trouble, that I would try writing a novel,” he told The Times in 2007.

That was the year “Bowl of Cherries,” which a New Yorker writer described as “equal parts ‘Catcher in the Rye’ and ‘Die Hard,’ ” was published.

Kaufman’s second novel, “Misadventure,” is due out this fall.

Born March 12, 1917, in Baltimore, Kaufman spent two years as a merchant seaman after high school.

After earning a bachelor’s degree in English from Johns Hopkins University in 1939, he moved to New York City and worked as a newspaperman for the Daily News and Newsday.

In 1942, he joined the Marine Corps and saw action on Guadalcanal, Guam and Okinawa.

In his later years, Kaufman wrote the screenwriting book “Plots and Characters: A Screenwriter on Screenwriting.”

Said Knopf, who met with Kaufman and other Hollywood veterans for weekly lunches at a Santa Monica restaurant: “When you were around him, he elevated you about the craft that you were in and made you want to do the very best you could possibly do.”

In addition to his son, Kaufman is survived by his wife of 66 years, Lorraine; his daughters, Mary Carde and Amy Burk; and seven grandchildren.

Services will be private.

Instead of flowers, donations may be made to the Motion Picture and Television Fund.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.