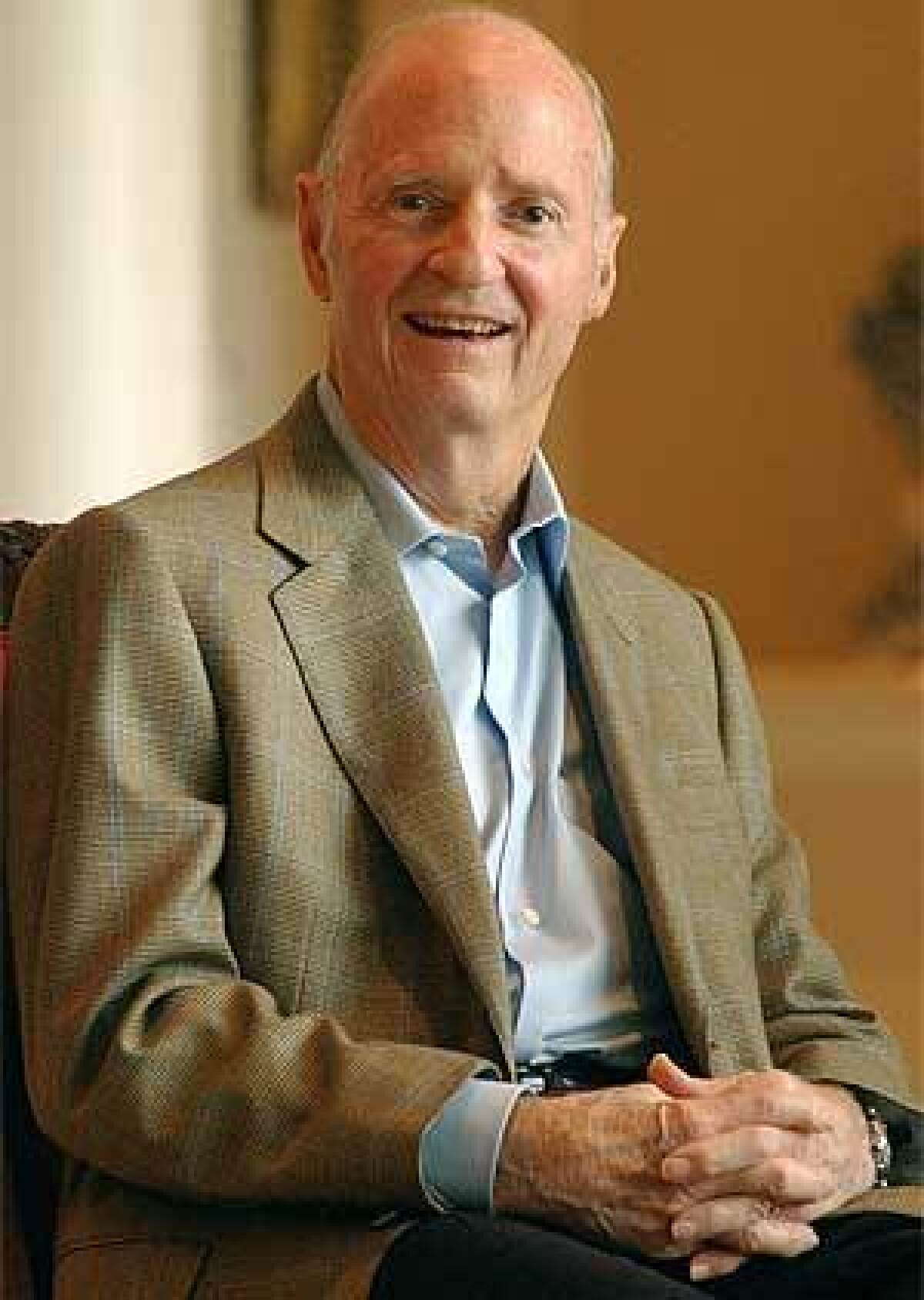

Norman Brinker dies at 78; restaurateur helped create a new way to dine

Norman Brinker, an innovative restaurateur who helped bridge the gap between fast food and fine dining with his casual, middle-of-the-road chains Chili’s, Bennigan’s and Steak & Ale, has died. He was 78.

Brinker, a resident of Dallas, died Tuesday at a hospital in Colorado Springs, Colo., while on vacation. The cause was complications from pneumonia, according to Brinker International Inc. spokeswoman Stacey Sullivan.

Brinker retired in 2000 as chairman of Brinker International, a Dallas-based restaurant group comprising the chains Chili’s Grill & Bar, On the Border Mexican Grill & Cantina, Maggiano’s Little Italy and Romano’s Macaroni Grill.

Chief among Brinker’s new concepts for eateries was the salad bar, which he popularized at Steak & Ale starting in the late 1960s. Besides asking diners to get up from their tables to serve themselves from a salad buffet, the Dallas-based chain also stood out for its cheerful servers’ stock introduction, “Hi, my name is Dirk, and I’ll be your waiter tonight.”

It was all part of Brinker’s idea to make the dinner experience more relaxed and casual. He followed up with a succession of restaurants featuring festive atmospheres and moderately priced menus that found a niche between inexpensive burger joints and pricey gourmet restaurants.

“You have about 45 minutes to convince the customer to come again; that’s your objective,” Brinker told the Memphis Commercial Appeal newspaper in 1991. “Your objective, once the customer is there, is to give them such a good experience, they’ll want to come again.”

Brinker’s plans were based on meticulous market research and attentive customer service, products of his business education at what was San Diego State College in the 1950s and a management training program at Jack in the Box when the San Diego-based chain had only a handful of outlets.

After starting at the bottom clearing tables and flipping patties at Jack in the Box, Brinker worked his way up the corporate ladder. He moved to Dallas in the early 1960s with his wife, San Diego tennis star Maureen Connolly, and bought a coffee shop.

Brink’s coffee shop didn’t succeed, but in 1966 Brinker’s next venture, Steak & Ale, did. He took the company public in 1971 and, after expanding to more than 100 locations, sold to Pillsbury Restaurant Group for $100 million in 1976. He stayed on with the company, eventually becoming president, and developed the Bennigan’s chain, known for its “fern bars” targeted at young, single diners. He also oversaw the Burger King fast-food chain before leaving Pillsbury in the early 1980s.

Brinker next set his sights on Chili’s, a modest Texas hamburger chain that he bought in 1983. As chairman and chief executive, he expanded the menu to include popular items including grilled chicken breasts, tuna steaks and sizzling fajita platters.

He transformed the company into Brinker International, which had more than 1,000 restaurants when he retired in 2000. It now has 1,700 locations in 27 countries.

Brinker was born June 3, 1931, in Denver and grew up an only child in Roswell, N.M., where his father and mother had a small farm. There he learned to ride a horse and later drew on his equestrian skills to earn a spot on the 1952 U.S. Olympic equestrian team.

He also competed in the 1954 modern pentathlon world championships while serving in the Navy during the Korean War. He married Connolly in 1955 and two years later graduated from San Diego State. The couple had two daughters, Cindy and Brenda, before Connolly died of cancer in 1969.

Brinker, who remained an avid horseman, was seriously injured during a polo match in 1993. Crushed by a horse, he was in a coma for three weeks and paralyzed for three months. Doctors doubted if he’d walk again, but Brinker was mobile and back at work within four months.

Brinker’s survivors include his wife, Toni Chapman Brinker, and daughters.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.