Robin Gibb dies at 62; rose to pop fame as one-third of the Bee Gees

Robin Gibb, a singer and songwriter who joined two of his brothers in forming the Bee Gees pop group that helped define the sound of the disco era with the best-selling 1977 soundtrack to”Saturday Night Fever,” has died. He was 62.

Gibb died Sunday after battling cancer and while recuperating from intestinal surgery, family spokesman Doug Wright announced.

This spring Gibb had been hospitalized in London with advanced colorectal cancer. He had intestinal surgery in March and, after contracting pneumonia, was unable to attend the April 10 premiere in London of “The Titanic Requiem,” a classical composition he wrote with his son, Robin-John, to coincide with the 100th anniversary observance of the luxury ocean liner’s sinking. He later fell into a coma but awoke April 21 after his family spent days singing to him at his bedside.

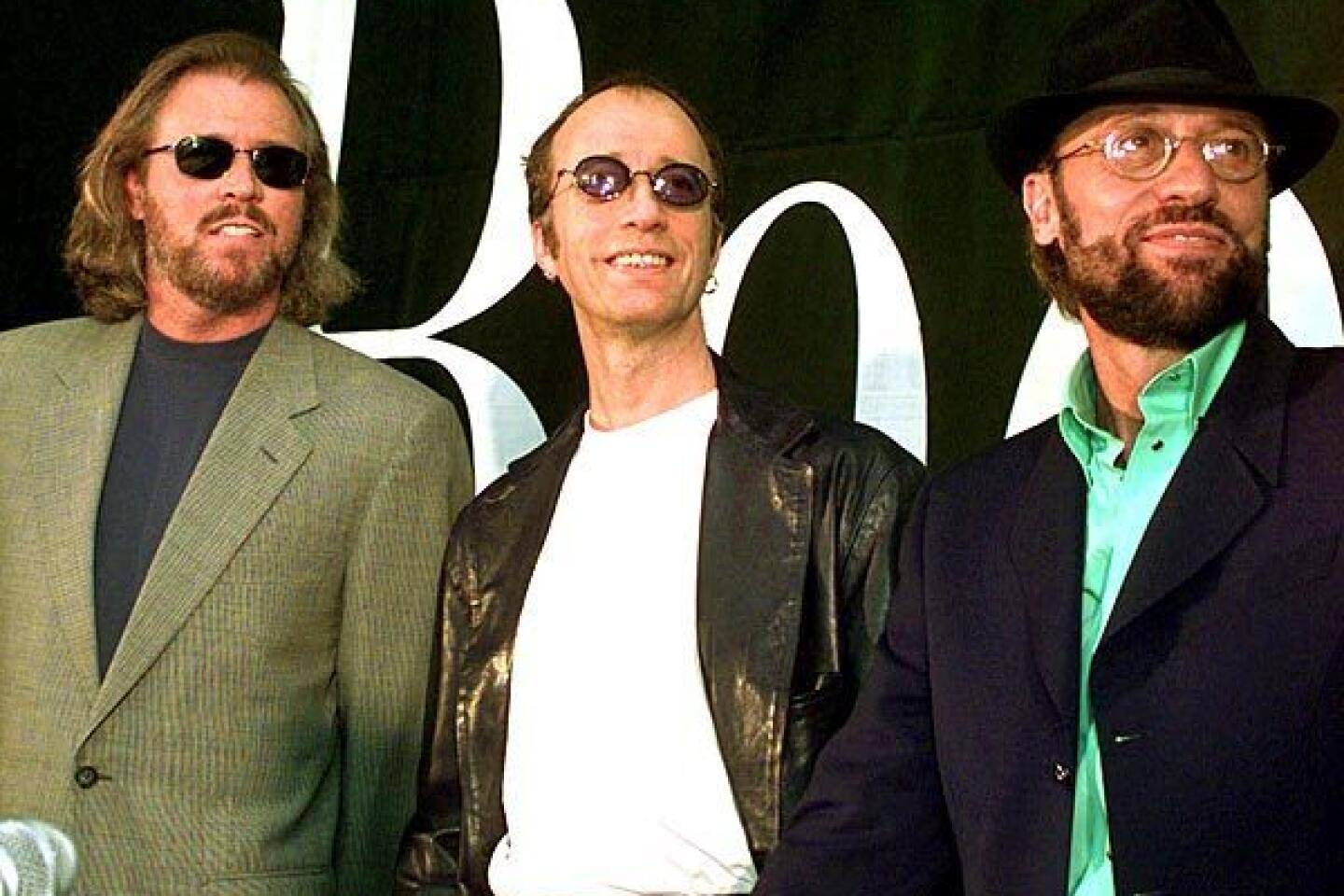

PHOTOS: Robin Gibb | 1949 - 2012

The Bee Gees energized the disco craze of the 1970s with such falsetto-laced hits as “Stayin’ Alive,” “Night Fever” and “How Deep Is Your Love?” from “Saturday Night Fever” and, from the successful follow-up album, “Too Much Heaven,” “Tragedy” and “Love You Inside Out.”

Their four-decade pop career was a roller-coaster ride of soaring success, plunging popularity, reinvention and difficult times.

The Bee Gees had nine No. 1 U.S. singles in the 1970s, won six Grammy Awards and were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1997.

Their youngest brother, Andy, who had a solo career apart from the Bee Gees, died of a heart condition at age 30 in 1988 after struggling with addiction. Robin’s fraternal twin, Maurice, also died prematurely, at 53 in 2003, of a heart attack while awaiting surgery for a blocked intestine. Robin survived a horrific train wreck in 1967 and later battled amphetamine dependence.

The Bee Gees — Robin, Maurice and their older brother, Barry — were an established pop act a decade before “Saturday Night Fever,” with a string of hits, some of which featured Robin’s plaintive, quavering vocal style, notably on “I Started a Joke.”

Robin and Maurice were born Dec. 22, 1949, on the Isle of Man in the Irish Sea, and music was always part of their household. Their father, Hugh, a drummer and big band leader, took odd jobs to support his wife, Barbara, four sons and daughter Lesley. As the boys grew up in Manchester, England, and then Brisbane, Australia, they listened to the harmonies of the Mills Brothers on their parents’ radio and Elvis Presley and other early rockers on their sister’s record player.

Barry, Robin and Maurice Gibb began honing their three-part vocal harmonies at a young age and performed in minor venues in England and in Australia, where they lived from 1958 to 1967. They called themselves the Brothers Gibb.

When the family returned to England, the brothers were signed to a contract by Robert Stigwood, a business associate of the Beatles’ manager, Brian Epstein. Now known as the Bee Gees, they had their first international hit, an evocative mood piece called “New York Mining Disaster 1941.”

The Bee Gees went on to fashion an eclectic collection of hits, all composed and written by the brothers. They began with lyrical ballads such as “Massachusetts” and “How Can You Mend a Broken Heart?” before moving into dance numbers “Jive Talkin’” and “You Should Be Dancing” and then taking off with the “Saturday Night Fever” soundtrack.

“This was the peak of record sales in all of history,” Robin Gibb told the Weekend Australian in 2009, referring to the band’s zenith in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s. “Since 1967, there have only been three albums that have truly affected the culture, and that’s [the Beatles’] ‘Sgt. Pepper,’ ‘Fever’ and [Michael Jackson’s] ‘Thriller.’ There’s not many people who know what that feels like. We’re like the guys who have been to the moon.”

“Saturday Night Fever” remained the biggest-selling soundtrack album until it was eclipsed in the early ‘90s by “The Bodyguard,” which was dominated by Whitney Houston songs.

And yet the Bee Gees never set out to exemplify the disco craze.

After Robin left the group in 1969 for a two-year stretch, they reassembled in Miami in the mid-’70s and experimented with synthesizers, a thumping beat and falsetto vocals. Working with Atlantic Records producer Arif Mardin, they made a comeback in 1975 with the R&B-influenced “Jive Talkin’” and “Nights on Broadway.”

“We didn’t think when we were writing any of our music that you would dance to it,” Gibb said in a 2010 interview with the New Zealand Herald. “We always thought we were writing R&B grooves, what they called blue-eyed soul. We never heard the word ‘disco,’ we just wrote groove songs we could harmonize strongly to, and with great melodies.”

To capitalize on their new sound, Stigwood asked the Gibbs to write four songs for a movie he was producing that was based on writer Nik Cohn’s 1976 story for New York magazine headlined “Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night.” John Travolta was to star in the movie that would introduce New York’s discotheque dance culture to mainstream audiences.

“When we gave the songs to the movie, we didn’t see it,” Gibb told Billboard magazine in 2001. “Nobody had any clue it was going to be big. The first time we saw the movie was when it came out.”

They came to personify the era, however, resplendent in their white satin suits, gold chains and flowing manes on the album cover.

But that also made them easy targets in the subsequent backlash against disco. The Bee Gees were treated “as if we had leprosy,” Robin told Entertainment Weekly in 1997. They had one top-10 single in 1989 and disbanded after Maurice died.

“As brothers we were like one person,” Gibb told the Daily Mail in 2011. “Me and Barry have always been the principal writers of the Bee Gees’ sound, and Maurice was the glue that kept the personalities intact. We were kind of triplets, really.

“I feel blessed I was born into a family that had Barry and Maurice in it. On a creative level it’s like winning the lottery — you can’t choose that.”

Besides his brother Barry, sister Lesley Evans and mother, Barbara, Gibb is survived by his second wife, Dwina, and their son, Robin-John; two children from his marriage to Molly Hullis that ended in divorce, Spencer and Melissa; and another daughter, Snow Robin, from a 2008 relationship.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.