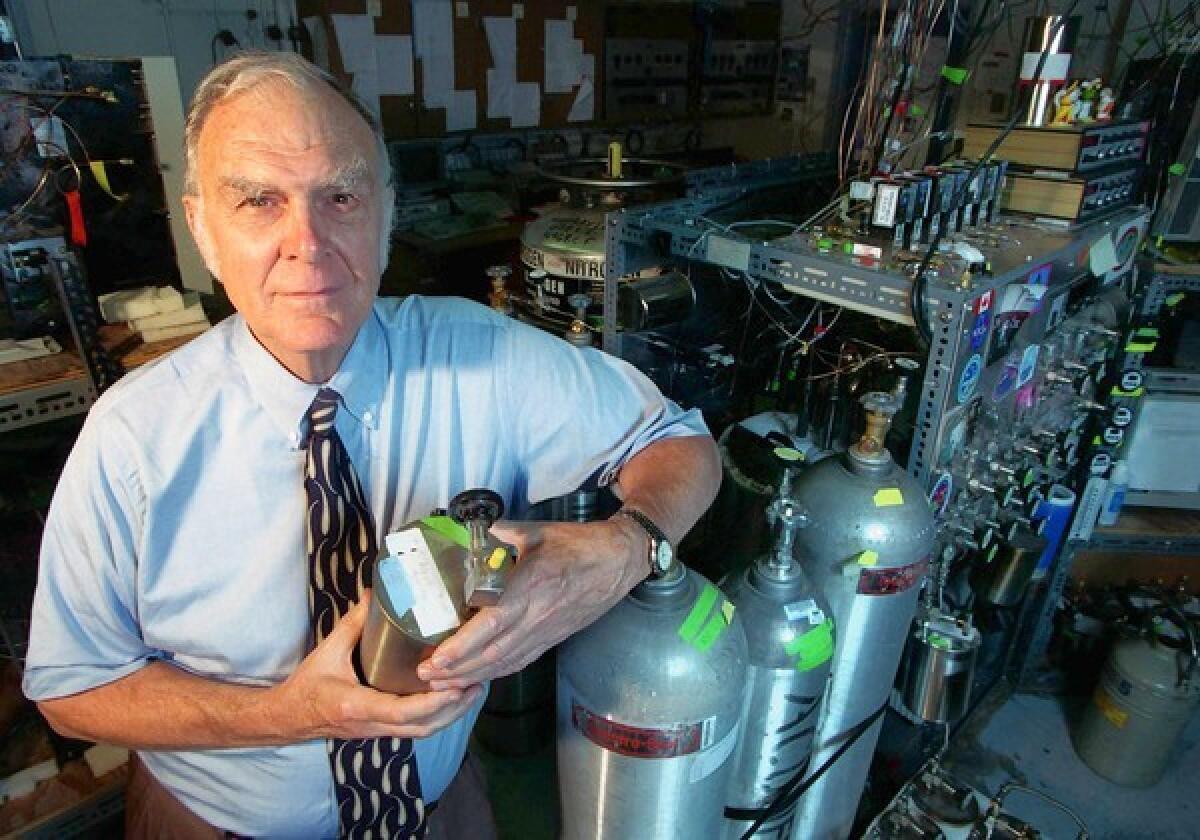

F. Sherwood Rowland dies at 84; UC Irvine professor won Nobel Prize

Notable deaths of 2011

- Share via

F. Sherwood Rowland, the UC Irvine chemistry professor who warned the world that man-made chemicals could erode the ozone layer, has died. He was 84.

Rowland, known as Sherry, died Saturday at his home in Corona del Mar of complications from Parkinson’s disease, the university announced.

In 1995, Rowland was one of three people awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry for his work explaining how chlorofluorocarbons, ubiquitous substances once used in an array of products from spray deodorant to industrial solvents, could destroy the ozone layer, the protective atmospheric blanket that screens out many of the sun’s harmful ultraviolet rays.

The prize was awarded more than two decades after Rowland warned of the problem, and challenges to his theory plagued him for many years before he won widespread recognition for his work and leaders of nations worldwide began to act to ban or reduce usage of the chemicals.

“We have lost our finest friend and mentor,” Kenneth C. Janda, UC Irvine physical sciences dean, said Sunday in an email to faculty. “He saved the world from a major catastrophe: never wavering in his commitment to science, truth and humanity, and did so with integrity and grace.”

The discovery “was about more than just stratospheric ozone,” said Donald Blake, a chemistry professor at UC Irvine who worked closely with Rowland for more than two decades. “It was about the whole environment and the realization that something we can do in California could have effects somewhere else in the world. It was the start of the global era of the environment.”

Born June 28, 1927, in Delaware, Ohio, Rowland as a child seemed destined for a life of intellectual pursuits. His father was a math professor at Ohio Wesleyan, and Rowland skipped several grades en route to an early entrance, at age 16, to the university where his father taught. He described his childhood home as brimming with books and his educational years as thoroughly enjoyable.

Rowland was too young to fight in World War II after his high school graduation, but after two years of college he enlisted in the Navy, where he found his athletic talent in high demand. A sports-loving youth who towered at 6 feet 5, he played on several Navy base sports teams.

He resumed his studies in chemistry at the University of Chicago in 1948. As Rowland later acknowledged, his timing was superb. The university was home to Nobel Prize winner Willard F. Libby — the chemist who developed the carbon-14 dating technique and who became Rowland’s mentor — and hosted such esteemed scientists as Enrico Fermi and Edward Teller. Although a dedicated student, Rowland found time to indulge in sports, playing baseball and basketball for the university and joining semi-professional baseball teams in Canada during the summers.

He married a classmate, Joan, in 1952, and after completing his doctorate, took a job at Princeton University as a chemistry instructor. He later joined the faculty at the University of Kansas, but when the UC Irvine campus opened in 1965, he was lured from Kansas to become the school’s inaugural chairman of the chemistry department.

From there, Rowland’s career became one of the most controversial and, eventually, illustrious among his UC Irvine colleagues. Long interested in the environment, Rowland attended a lecture in 1972 about atmospheric concentrations of chlorofluorocarbons used in many consumer and industrial products, such as coolants in refrigerators and air conditioners. The inert chemicals, it was believed, would serve as effective tracers for identifying air mass movements. But Rowland began wondering what eventually happened to the compounds in the atmosphere.

In 1973, after only a few months of work, he and a young member of his research group, Mario Molina, realized that the chemicals were involved in a chain reaction that depleted stratospheric ozone.

Rowland and Molina, who is now at UC San Diego, were initially stunned by their findings. When he arrived home from the office one evening and was asked about the work by his wife, Rowland answered grimly, “The work is going well. But it looks like the end of the world.”

Rowland was resolute about his obligation to speak up, however, Blake said.

“He seemed to be a person who had a tremendous amount of inner confidence,” he said. “He was convinced he was right and went with it. But he was a cautious man. He did not espouse this to the world without giving it a lot of thought.”

The pair’s findings, published in the journal Nature in 1974, were met with scorn by the chemical industry and even by many scholars. For a decade, Rowland and Molina persevered to prove their hypothesis, publishing numerous scientific papers and speaking to sometimes hostile audiences at scientific conferences. It took almost 15 years for the international scientific community and chemical industry to accept the pair’s findings.

Manufacturers began to phase out chlorofluorocarbons in the late 1980s, prompted by the discovery of an ozone “hole” over Antarctica that formed each winter in response to weather conditions and the falling worldwide levels of ozone. The Montreal Protocol, a landmark international agreement to phase out CFC products, was signed by the United States and other nations in 1987.

The protocol was proof that nations could unite to address common environmental threats, Rowland contended. “People have worked together to solve the problem,” he said.

Rowland considered the phase-out of CFCs his greatest achievement, Blake said. His receiving the Nobel Prize, alongside Molina and Paul J. Crutzen of the Netherlands, in 1995 was icing on the cake. In his Nobel banquet speech, Rowland noted mankind’s long fascination with the atmosphere. But it was his own dogged curiosity that spared the world from a potential environmental crisis.

“He was the perfect spokesperson for this issue,” Blake said. “He was austere, well-spoken and had a lot of confidence. He didn’t get emotional” when challenged.

The ozone discovery earned Rowland many prizes and prestige. He served as president of the American Assn. for the Advancement of Science and was a longtime member of the National Academy of Sciences. He remained active at UC Irvine long after most of his peers retired and until earlier this year continued working in his campus office at Rowland Hall, which is named for him. As the Donald Bren Research Professor of Chemistry and Earth Science, he traveled widely to lecture and consult on environmental issues and prodded younger researchers in the Irvine chemistry department.

Besides his wife of nearly 60 years, Rowland is survived by two children, Ingrid and Jeffrey, and two grandchildren.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.