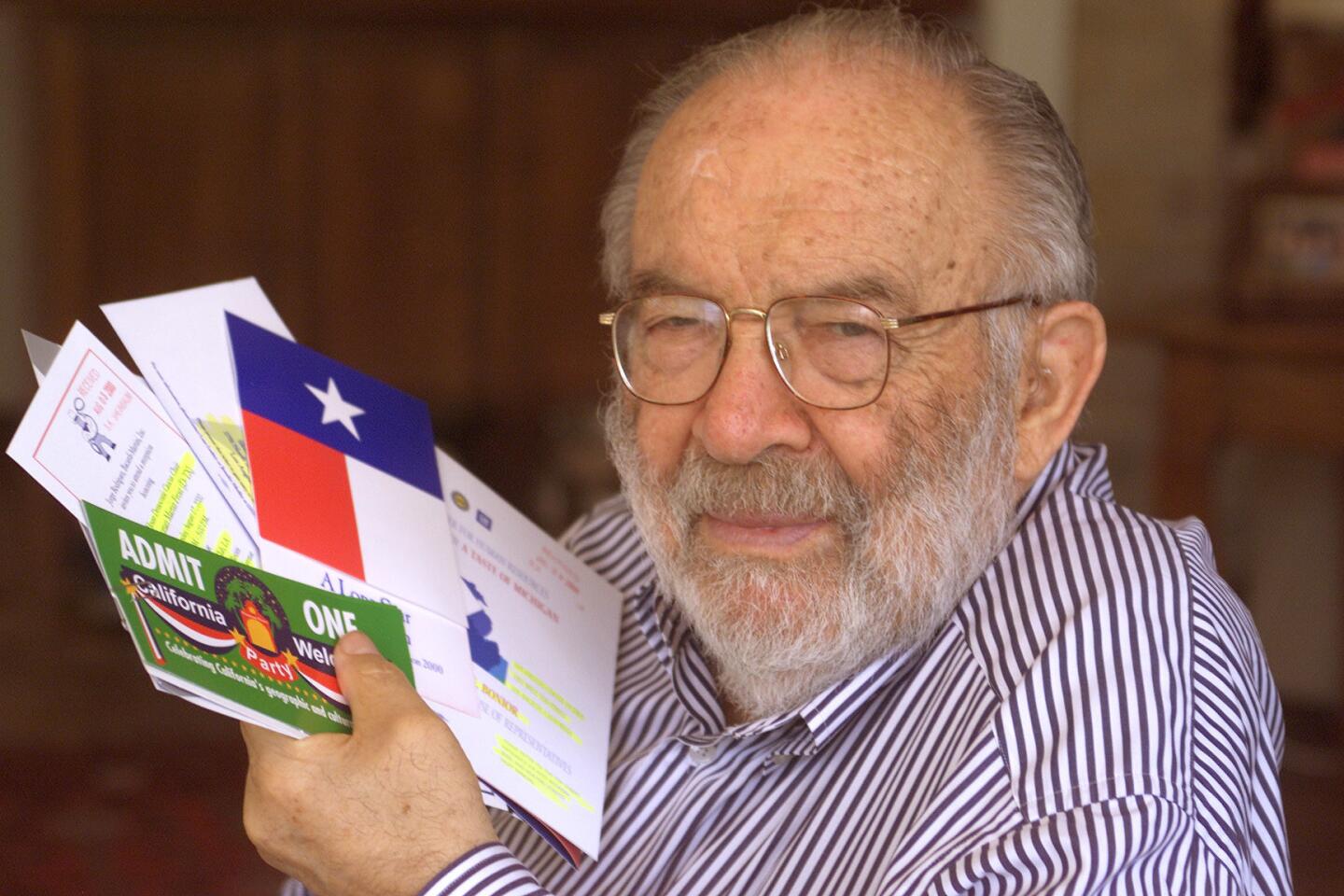

Stanley Sheinbaum, L.A. liberal lion who shaped decades of political dialogue, dead at 96

- Share via

For more than four decades, Stanley Sheinbaum regularly gathered moguls, presidents, celebrities and activists in his Brentwood living room to sip wine and debate the issues of the day. King Hussein and Queen Noor of Jordan, Bill and Hillary Clinton, Norman Lear, Barbra Streisand and Warren Beatty were among the many famous faces who participated in the vibrant salons Sheinbaum and his wife, Betty, held at their art-filled home on exclusive Rockingham Avenue.

But more than a high-powered host, Sheinbaum often was a change agent, whose fingerprints can be found on a remarkable array of notable events.

In the 1960s he engineered the release of Andreas Papandreou, the Greek leader who had been imprisoned by a military junta. In the 1970s he was the chief fundraiser for Daniel Ellsberg’s defense in the Pentagon Papers trial. In the 1980s he led a delegation of American Jewish leaders who persuaded Palestine Liberation Organization Chairman Yasser Arafat to renounce terrorism and accept Israel as a state. And in the 1990s he headed the Los Angeles Police Commission after the beating of motorist Rodney King and helped drive controversial police Chief Daryl Gates from office.

NEWSLETTER: Get the day’s top headlines from Times Editor Davan Maharaj »

“He’s a pot boiler,” Lear once said of his longtime friend and ally. “Something is always brewing in Stanley.”

Sheinbaum, who said “helping to keep a liberal voice alive” was the overarching goal of a lifetime of activism, died Monday at his home in Brentwood, according to his assistant Marti Maniates. He was 96.

He often took stands that invited outrage. When he was photographed shaking hands with Arafat, fellow Jews called him a traitor and a dead pig was thrown on his driveway. When he criticized the Los Angeles Police Department, he rankled Gates, who called him “a pain in the ass.”

“He had courage,” said Rep. Maxine Waters (D-Los Angeles), who met the peripatetic advocate in the 1970s before she held political office. “I don’t know anyone who is basically a volunteer activist who played the role Stanley has.”

His fortune gave him the freedom to agitate and aggravate. A child of the Depression who trained as an economist at Stanford University, he gained his wealth through marriage to Betty Warner, the daughter of movie mogul Harry Warner, and doubled it through shrewd investment.

He belonged to the “Malibu Mafia,” a small group of socially conscious Westside moguls, including Lear and Max Palevsky, who channeled hundreds of thousands of dollars into progressive causes and candidates. George McGovern, John Anderson, Jesse Jackson and Bill Clinton were among the politicians who relied on Sheinbaum’s support.

Born in New York on June 12, 1920, Sheinbaum was the son of a leather-goods manufacturer whose company collapsed during the Depression. To earn money, young Stanley sold magazines, clerked in a department store and worked as a delivery boy. When his father was able to reopen his business, Sheinbaum learned to operate a sewing machine and became so skillful he could sew dresses.

He had courage. I don’t know anyone who is basically a volunteer activist who played the role Stanley has.

— Rep. Maxine Waters (D-Los Angeles)

He had little interest in school and the poor grades to prove it. He put some of the blame on his hyper-critical mother. “In fighting against the inevitable feeling that I was no good, I, of course, became no good,” he wrote in his 2012 memoir, “Stanley K. Sheinbaum: A 20th Century Knight’s Quest for Peace, Civil Liberties and Economic Justice.”

After his father’s company failed a second time, Sheinbaum drifted until, at age 20, he joined the Army. He spent most of World War II making maps.

Following his discharge in 1946, he applied to 33 colleges but was rejected by all of them. He returned to high school at age 25, doing well enough to gain admission to Oklahoma A&M. He later transferred to Stanford and graduated summa cum laude in economics. He traveled to Paris on a Fulbright fellowship to study international monetary affairs.

In the late 1950s he was hired to teach economics at Michigan State University, which assigned him to a program providing technical assistance to South Vietnam. He became the coordinator in 1957, not knowing that the program was a front for the CIA.

When he finally learned the truth, after 18 months in the job, it radicalized him.

“I realized then the real threat was not in Vietnam but right here at home,” he told The Times many years later.

Sheinbaum resigned as coordinator in 1959 and in 1960 joined the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions in Santa Barbara as a research economist. He had remained quiet about the CIA’s links to the Michigan State program until he was contacted by journalist Robert Scheer, who had discovered the connection on his own. Sheinbaum wound up collaborating with Scheer on an article published in Ramparts magazine in 1966 that exposed the program.

The CIA launched an investigation of Ramparts and a campaign to discredit it, which quickly evolved into a broader program of domestic political espionage, according to journalist Angus Mackenzie in his 1998 book “Secrets: The CIA’s War at Home.” Mackenzie wrote that Sheinbaum was “the first person to go public with his experience of CIA activity in the United States — a story about the Agency’s infiltration of a legitimate civilian institution.”

Sheinbaum became an outspoken critic of U.S. policies in Vietnam, appeared at antiwar teach-ins around the country and twice ran for Congress as a peace candidate.

After losing both Congressional races, he was tapped to organize support for Ellsberg, the Vietnam war critic arrested in 1971 for leaking the Pentagon Papers to the New York Times, and his co-defendant Anthony Russo. Sheinbaum raised nearly $1 million.

Most of the funds came in small contributions from thousands of individual donors, but Sheinbaum organized one big-ticket event that featured Streisand and raised $50,000. “Had Stanley not put on that event and raised $50,000 the trial would have ended and I believe Nixon would have stayed in office for the rest of his term,” Ellsberg said in “Citizen Stan,” a documentary directed by Patty Sharaf. “And the war would have continued.”

The case ultimately was dismissed over revelations that a break-in at Ellsberg’s psychiatrist’s office was committed by Nixon White House operatives who later would be tied to the Watergate affair.

The Ellsberg work plunged Sheinbaum into Los Angeles political life. As chairman of the fundraising arm of the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California from 1972 to 1982, Sheinbaum led efforts that increased the organization’s budget from $60,000 to more than $700,000, enabling it to pursue the long-running Los Angeles school desegregation case and fight the LAPD on policies such as the use of chokeholds and battering rams.

Stanley would always think through what was morally right, what needed to be done. And he was never fazed by criticism or people who turned away from him.

— Ramona Ripston, ACLUâs retired longtime executive director

“Stanley would always think through what was morally right, what needed to be done. And he was never fazed by criticism or people who turned away from him,” said Ramona Ripston, the ACLU’s retired longtime executive director.

When he stepped down from the ACLU post, he said part of the reason was to devote more time to his duties as a UC regent. Appointed in 1977 by Gov. Jerry Brown, he served for 12 years, during which he chaired a committee on the social effects of UC investments and advocated divestment of interests in South Africa because of apartheid.

In 1988, he was asked by officials from the Swedish foreign ministry to organize a group of American Jewish leaders to meet with the PLO and persuade them to adopt positions that would satisfy U.S. requirements for opening peace talks. That effort culminated in the breakthrough with Arafat in Stockholm on Dec. 6, 1988, and paved the way for a historic 1993 meeting at the White House between Arafat and Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin.

Akiva Eldar, former U.S. bureau chief of the Israeli newspaper Haaretz, recalled that Sheinbaum was credited with helping lay the groundwork for the American Jewish peace movement.

“He was one of the heroes of the Israeli peace camp,” Eldar said Monday.

But, at the end of the Stockholm negotiations, Sheinbaum was photographed with his arm around Arafat, an unpardonable sin to many Jews. Sheinbaum said later that he felt no guilt over his role in the Stockholm summit. “I feel very Jewish about going.... I think I did something that I would have done for any people if I had the opportunity. And in this particular instance, I did it for Israel.”

It was not the first time he had a role in world affairs.

When Papandreou was imprisoned by a military junta in Greece in 1967, Papandreou’s then-wife, Margaret, recruited his friend and fellow economist to help free him. Sheinbaum, who had met the Greek-born economist from UC Berkeley years earlier, spent months in fruitless strategizing until he received a call to fly to Paris. There he met with several of the junta’s chief witnesses against Papandreou. They told Sheinbaum their testimony had been coerced.

Sheinbaum persuaded them to come to the U.S. to tell their story to Ramparts. The resulting article “took the ground out from under the junta’s case,” Sheinbaum said, and Papandreou was released.

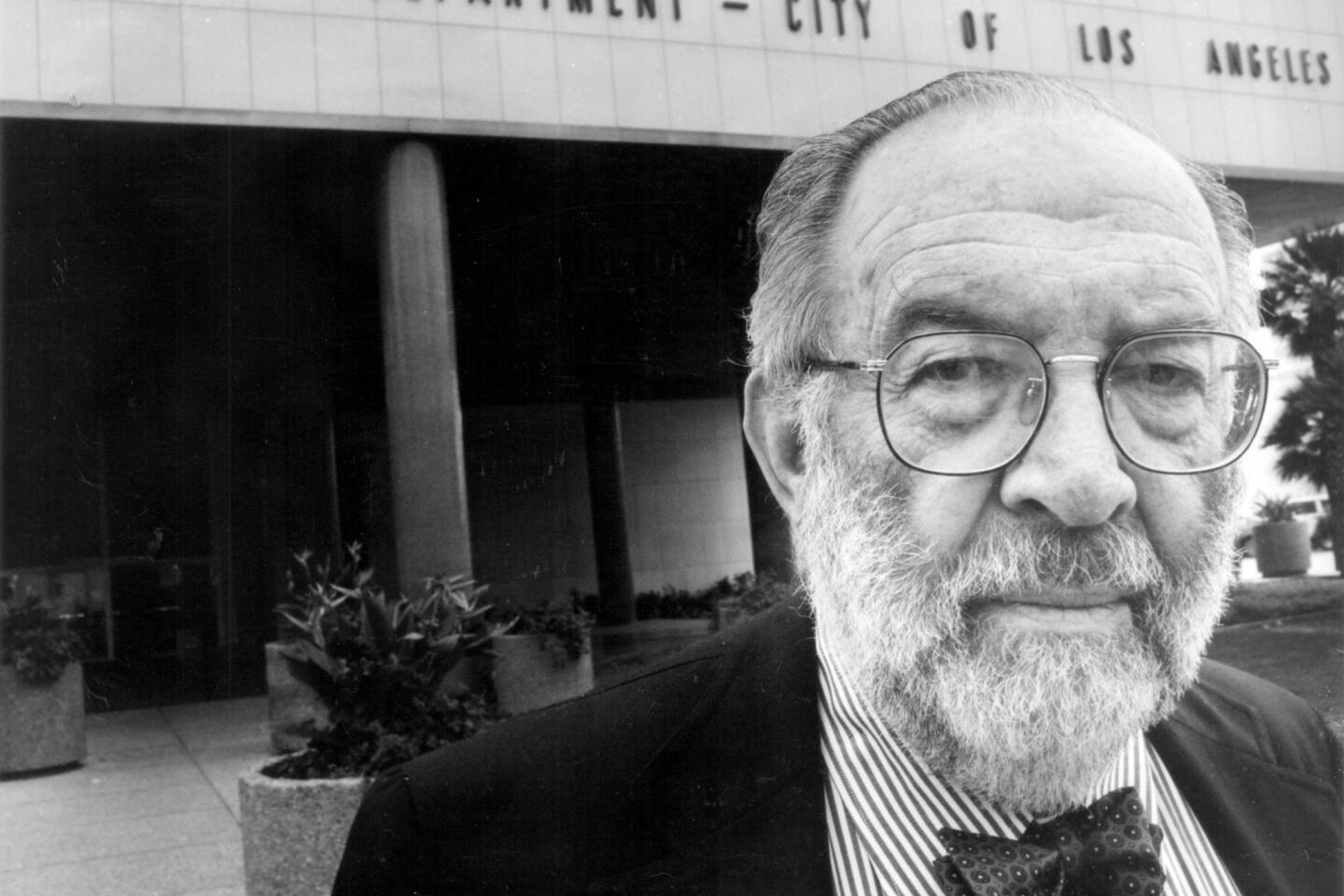

In spring 1991, Sheinbaum sent word to Mayor Tom Bradley through an intermediary that he was interested in joining the Police Commission. Coincidentally, the message was relayed on the night that King was beaten during a traffic stop by Los Angeles police officers. Two weeks later, after the videotaped encounter caused a national furor, the mayor called to tell Sheinbaum he had the job.

From the outset, Sheinbaum’s civil liberties background set him at odds with Chief Gates, who was under fierce attack for his department’s handling of the King incident. During the 1992 riots Sheinbaum walked the streets of South Los Angeles and helped defuse a tense situation at a park where protesters, including many gang members, had been ringed in by police.

“Most people would say he had no business there,” Waters said of Sheinbaum, who helped her escort the protesters through the police ring and out of the park. “He was an unusual human being.”

On the Police Commission, Sheinbaum became the overseer of its efforts to oust Gates and hire Willie L. Williams. He also helped spearhead commission efforts at reforming the department.

“He was a vital member of the police commission at a terrible time in the life of Los Angeles when the LAPD was at its lowest ebb,” former Los Angeles City Council member Joy Picus told The Times recently. “Stanley’s thoughtful and almost radical approach to things was helpful at a time like that.”

Even Gates acknowledged that Sheinbaum had been effective.

“Stanley Sheinbaum was supposed to be an irritant. He proved to be one — a pain in the ass, most of the time,” Gates said in the film “Citizen Stan.”

When Sheinbaum was replaced on the Police Commission by Mayor Richard Riordan in 1993, he sounded a surprising pro-police note, saying he regretted the panel had failed to give the public a full appreciation of the challenges of policing

“I’m not better than anybody else,” he once said, “but I do have a commitment to a good society and time to work on that.”

Special correspondent Josh Mitnick in Tel Aviv contributed to this report.

ALSO

Greta Friedman, woman in iconic WWII Times Square kiss photograph, dies at 92

Jerry Heller, controversial early manager of N.W.A, dies at 75

David Huddleston, who played the title role in ‘The Big Lebowski,’ dies at 85

UPDATES:

12 p.m.: This article was updated with additional details.

This article was originally published at 6:10 a.m.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.