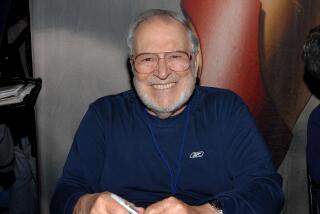

Joe Kubert dies at 85; comics artist created ‘Sgt. Rock’

- Share via

Joe Kubert was never a superstar comics artist — his work didn’t have the necessary bombast or polished edges — but the man who drew ragged, soulful soldiers in “Sgt. Rock,” “The Haunted Tank” and “Enemy Ace” did something his characters would have admired: Kubert marched farther and longer than anyone else and proved himself a natural leader.

Kubert, 85, who died Sunday in Morristown, N.J., of multiple myeloma, leaves behind a legacy spread across comic books published in eight decades and built into the walls of the Kubert School. The school, founded in 1976 in Dover, N.J., by the artist and his wife, Muriel, is the nation’s only accredited trade school for comic book artists. Its inspiration came from Kubert’s earliest days in the business when he was a preteen protege in a comic book production shop in Manhattan in the late 1930s.

By age 13, Kubert was sweeping floors and erasing the pencil lines on pages of inked artwork in Harry Chesler’s bustling production studio, which was handling the demand surge that followed the June 1938 debut of Superman in “Action Comics” No. 1. Kubert’s own artwork was first published in March 1942 with a six-page tale of Volton the Human Generator, who traveled through electrical wires and protected Empire City.

Volton fizzled but, 70 years later, Kubert was still energized and working at a high level — the octogenarian had been working in recent months with his son, Andy, on the high-profile DC Comics mini-series “Before Watchmen: Nite Owl.” Andy’s brother, Adam, is also a comic book artist; both teach at the Dover academy.

“We are saddened to learn of the death of our colleague and friend Joe Kubert,” DC Comics said in a statement. “An absolute legend in the industry, his legacy will not only live on with his sons, but with the many artists who have passed through the storied halls of his celebrated school.”

Instead of the majestic and the muscle-bound, Kubert’s art seemed tattered at the edges and populated by rangy heroes with haunted eyes. That didn’t suit Metropolis or Gotham City duty, but it made him perfect for the vines of jungle adventure (“Tarzan of the Apes,” “Korak,” “Tor,” “Rima the Jungle Girl”) and the foxholes of war comics, none more famously than “Sgt. Rock.”

Sgt. Frank Rock, the everyman leader of Easy Company, was introduced in 1959 by Kubert and writer Robert Kanigher, and he would continue fighting World War II on a monthly basis well into the MTV era. Kubert would correct people who mentioned his success in war comics — he considered them “antiwar” comics — and that view was pinned to the page starting in 1967 when the words “Make War No More” became a familiar motto on the closing page of Sgt. Rock stories.

“Joe, in his way, was a primitive; he drew from his gut,” said Neal Adams, the artist who shook up comics in the 1960s with a sleek style leaning toward photo-realism. “Joe, because of his gritty style, because of his down-in-the-dirt approach, mixed the heroic with the terribleness of war, and the dirt of war, and the grit of war. He never made it seem appealing, but, to men, the nature of war is that you can be a hero. The cost, however, is one of the things that Joe showed in his work.”

The search for authenticity and the eagerness to stay a student himself led Kubert to challenging work into his 80s. In 2010, Kubert completed and published one of his most celebrated works, “Dong Xoai, Vietnam 1965,” a war story based on his interviews with veterans of the U.S. Special Forces. Andrew Farago, curator of the Cartoon Art Museum in San Francisco, said Kubert’s stamina and sustained relevance were amazing to behold.

“He didn’t follow trends and never changed his style to fit in with whatever was popular at the time.... The work that Joe created in his 80s was just as strong as the material he produced in his 40s, if not stronger,” Farago said. “There were very few artists in Joe’s league, and fewer still that maintained that level of quality throughout their entire careers.”

Yosaif Kubert was 2 months old when he, his older sister and their parents arrived at New York’s Ellis Island in 1926. The family hailed from a village called Ozeryany in what was southern Poland and is now Ukraine.

The family settled in Brooklyn, where Kubert’s father worked as a kosher butcher. One day he brought home a life-changing treasure: an artist table for his son, who was obsessed with comic strips, especially Hal Foster’s “Tarzan.” Decades later, Kubert would draw Edgar Rice Burroughs’ jungle hero, and earlier this summer he reflected on the power of those newsprint images.

“Reading Foster’s ‘Tarzan’ back in the stone age was one of the very important things that occurred in my life that pointed me toward the things I do today,” Kubert said in June phone interview. “When I was a kid, I didn’t know why it was so powerful or why I enjoyed it so much. But as I got older and I got into the business myself, I tried to analyze it.... It was his ability to tell a story and do it with images that were still — they weren’t moving, not animated at all — but they were living. That character was alive, and for me those images moved even if they didn’t.”

Walt Simonson, the artist best known for fan-favorite Marvel runs on “Thor” and “X-Factor,” said the Kubert version of Tarzan is dazzling to look back on. “Joe Kubert’s Tarzan is, for me, the perfect match of artist and subject,” Simonson said. “Joe’s drawing is beautiful and wild, and he captures the essence of Tarzan’s adventures the same way Burroughs does, by appealing directly to the heart.”

Kubert’s work often reflected his faith, whether it was “The Adventures of Yaakov and Yosef” strip he did for Moshiach Times or “The Bible,” a tabloid-sized project he did in 1975 for DC Comics, which promised “the most exciting tales from the beginning of time” with images of Cain, Adam and Noah’s ark on the cover. There were plenty of superhero comics in his body of work, of course, and his years of drawing Hawkman’s wide, gray wings created the resonant image of the enduring DC hero.

This summer IDW Publishing in San Diego announced that a lavish new hardcover reprint of Kubert’s Tarzan comics would be coming in September. For Kubert, that news was a valentine to “a very special highlight” in his career — and he was pleased it would come in the same calendar year as his “Before Watchmen: Nite Owl” collaboration with his son.

In addition to his two artist sons, Kubert’s survivors include two other sons, David and Danny, and a daughter, Lisa Zangara. His wife, Muriel, died in 2008.

The father of five said the only thing better than seeing the name Kubert on a comic book cover was seeing it there twice.

“It’s the cherry on top of the whipped cream,” Kubert said in June. “You know this business is not something you can push people into, but once bitten, it’s not something you can pull them out of.... The fact that my two boys Adam and Andy love what they do as much as I do, well, you know what that is? That’s purely a miracle.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.