Inside a Missouri abortion clinic under siege: sobbing, breakdowns and conflicted doctors

- Share via

Reporting from St. Louis — Working at the only abortion clinic left in Missouri, Dr. David Eisenberg often feels he needs a sign on his forehead that says, “I’m sorry.”

I’m sorry that, in this really difficult and stressful period of your life, I don’t know whether I’m able to take care of you.

I’m sorry that you have to wait at least three days for me to provide the care you need.

I’m sorry that the state is forcing me to do a pelvic exam when there’s no medical reason to make you uncomfortable today.

His clinic — Planned Parenthood of the St. Louis Region and Southwest Missouri — is now under siege.

Last week, days after the state’s governor signed a law banning abortions after eight weeks of pregnancy, state officials moved to shut down the clinic, which would make Missouri the first state without a place for women to legally have the procedure since 1974, the year after the U.S. Supreme Court guaranteed the right to the procedure.

Planned Parenthood filed a lawsuit seeking to prevent the state from blocking the facility from providing abortions, and its future now rests with a court in St. Louis, where the nonprofit is fighting the state’s refusal to renew its license to perform abortions.

As legal teams spar, state officials are also requiring physicians to perform a pelvic exam at least 72 hours before every abortion — a step that critics say is aimed solely at deterring women from following through with the procedure.

Eisenberg has conducted tens of thousands of pelvic exams over the years. But he said performing them several days ahead of an abortion feels like a violation.

“What I realized was I effectively have become an instrument of state abuse of power,” he said. “As a licensed physician, I am compelled by the state of Missouri to put my fingers in a woman’s vagina when it’s not medically necessary.”

This is not what Eisenberg envisioned when he moved to St. Louis a decade ago to be the regional medical director of Planned Parenthood.

He knew Missouri lawmakers were hostile to abortion — that in the 1980s the state became the first to require a doctor performing abortions to have admitting privileges at a local hospital, a rule that led many clinics to close.

But Eisenberg was eager to take on the challenge of mainstreaming women’s access to abortion in Missouri.

“Look, I found my ideal job!” he told his wife, Dr. Erin King, back then.

As a fellow gynecologist and abortion provider — they trained together in Chicago — she shared his idealism. And the job she found at a clinic less than 10 miles away in Illinois provided a template for what was possible. The state is something of an oasis for abortion access in the Midwest.

“We hoped we could move the needle in that direction and normalize the healthcare that we provide,” Eisenberg said.

But over the last decade, Missouri has imposed a raft of abortion restrictions: requiring patients to have an “informed consent” meeting with physicians to discuss the risks associated with abortion and then wait at least 72 hours before returning for the procedure; restricting insurance policies from covering abortion; and prohibiting the remote prescribing of medication to cause abortion.

Four outpatient health centers providing abortion care have closed in the last decade, leaving only Eisenberg’s clinic.

“In reality, over the last 10 years, we have been digging our heels in and trying not to slide backwards,” he said. “And we are sliding faster and deeper.”

With all the legal uncertainty, fewer patients are showing up now for appointments at the St. Louis clinic, a massive grey complex with bricked-up windows and a metal detector that scans everyone who enters the front door.

But when they do come, they have a flurry of questions: How long will the clinic remain open? What’s going to happen in court? Will I be able to get an abortion next week?

The clinic’s license was set to expire last Friday at midnight after state officials refused to renew it, citing safety concerns. A judge has allowed Planned Parenthood more time to resolve its dispute with the state and, as hearings continue, Eisenberg has resolved to focus on patients.

“I don’t know enough about what’s happening in the court, so I’m going to try to ignore it as best I can and just take care of the 15 women who are scheduled for abortions today,” he said Tuesday morning before heading to surgery in navy scrubs.

Just a few rooms down a hallway lined with framed prints of pink and purple flowers, a patient sobbed and shrieked as she waited for her procedure.

“She is terrified she’s going to be on the table and then the judge is going to say, ‘No, we’ve got to stop,’” said Kawanna Shannon, the clinic’s director of surgical services. “I told her that’s not going to happen. But this is hard on people. They’re stressed out.”

In the week since the state tightened its rules on pelvic exams, a doctor at the clinic has spoken out after being forced to carry out the exam on a woman who was terminating a pregnancy because the fetus had serious physical abnormalities.

“That woman had a complete breakdown,” Shannon said, adding that the doctor “felt horrible as a physician to have to perform a pelvic exam on a woman who was already going through such hardship.”

Earlier this year, a state inspection cited the clinic for the timing of pelvic exams. State officials insist that conducting the exam days before an abortion — even for nonsurgical abortions in which patients take pills — is in the interest of women’s safety.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists states that pelvic exams should be performed when “indicated by medical history or symptoms” and “based on a shared decision between the patient and her obstetrician–gynecologist.”

In an effort to keep the facility open, Planned Parenthood agreed to change its policy.

If the clinic loses in court, patients in Missouri will be forced to leave the state for abortions.

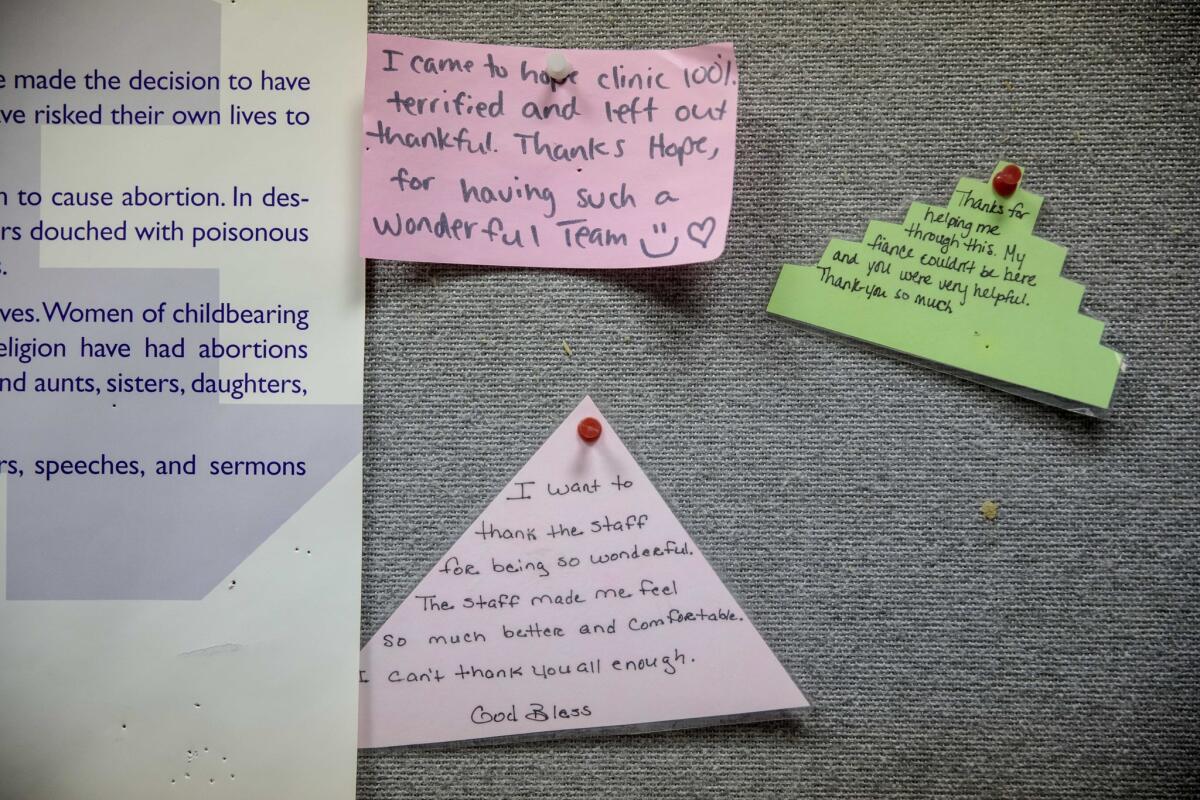

Many of Eisenberg’s patients would wind up just across the Mississippi River in Granite City, Ill., at the Hope Clinic for Women, where King is the executive director.

Already, more than half of her patients come from Missouri, and she is holding crisis meetings and hiring more staff to prepare for a greater influx.

Women there face none of the hurdles they do in St. Louis.

The facility is decorated with purple vases filled with plastic flowers and inspirational posters proclaiming “Our Bodies. Our business. Our rights” and “Well behaved women rarely make history,” and the process for getting an abortion is straightforward.

“We can just be their normal doctors,” King said. “If you said, ‘Look, I want to get my tooth pulled,’ you would go to a dentist, check in and get your history taken. They would do your procedure and you would go home. That’s exactly how we approach reproductive health care here in Illinois.”

Over the years, King has listened, incredulous, as her husband describes the rules Missouri forces him to comply with.

“Like, my jaw is on the floor,” she said. “I’m looking at him asking, ‘Is this a joke? Are you being serious?’”

Both agreed the last week had been the lowest point.

“I’ve only seen him close to tears a few times in our lives, you know?” King said on a recent afternoon in between ultrasounds. “Maybe our wedding, when our children were born, and then last Thursday, when he got home from work.”

Even if Eisenberg’s clinic manages to renew its license, its legal battles will continue.

Last month, Republican Gov. Mike Parson signed a law banning abortions at eight weeks of pregnancy, without exceptions for cases of rape or incest — a notable tightening of current state law that allows abortions up to 21 weeks and six days.

“We are sending a strong signal to the nation that, in Missouri, we stand for life, protect women’s health, and advocate for the unborn,” Parson said.

If the law is not successfully challenged in court, it will go into effect in late August.

Amid all the chaos, the couple made a point of staying up late last Friday night to watch Illinois lawmakers pass the Reproductive Health Act, a sweeping bill that affirms women’s “fundamental” reproductive health rights and repeals older, unenforced laws that restricted late-term abortions and imposed criminal penalties on physicians who perform them.

After so much negative rhetoric in Missouri, they were heartened to see Illinois state Sen. Melinda Bush, a sponsor of the bill, repeat the message that they have said over and over for years: We just need to trust women.

When Eisenberg finds himself overwhelmed, he focuses on talking to his patients: the women who struggle to make ends meet, who have two or three jobs, who already have children and are trying their best to provide them with healthy meals.

“I believe that we are on the right side of history,” he said. “If you’re going to make positive change and improve the health and well-being of a community, you have to go where that change is needed.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.