Transfer of Arizona national forest to mining firm divides blighted town

reporting from SUPERIOR, Ariz. — Leslie Martin’s boutique is among the few businesses on Superior’s Main Street not boarded up, making it one of the last places where locals can still gather to talk.

And she plans to keep it that way by asking visitors to leave whenever they bring up an uncomfortable subject: the Resolution Copper mine.

“My store’s a little Switzerland,” said Martin, who insisted on stepping outside even to explain the rules. “It’s off-limits to mine discussion. It’s just a rule I set right away because it got loud in there.”

It figures to get louder now that Congress has approved the transfer of 2,400 acres of national forest to a subsidiary of two foreign mining companies. The transfer ended a nearly decade-long fight over access to the federally protected land and ignited a feud that has split families, ended lifelong friendships and turned miners and former miners against one another.

On one side is Resolution Copper Mining, which is owned by the British-Australian company Rio Tinto Group and Melbourne, Australia-based BHP Billiton Ltd.

Resolution Copper says a mile-wide copper ore body 7,000 feet below the ground outside Superior is among the largest and richest in the world.

And bringing it to the surface, the company says, will create 3,700 jobs and have an economic impact of $61.4 billion over 60 years — numbers that have many residents in the blighted town 60 miles southeast of Phoenix rallying behind the company.

On the other side is a coalition of environmentalists, Native Americans and even former miners whose families have worked Arizona’s Copper Triangle for generations.

Tony Acosta, a former miner whose family has been in the business nearly 60 years, said copper once gave the town stability and a sense of unity. But the Resolution Copper project has changed all that.

“It’s divided the town,” he said.

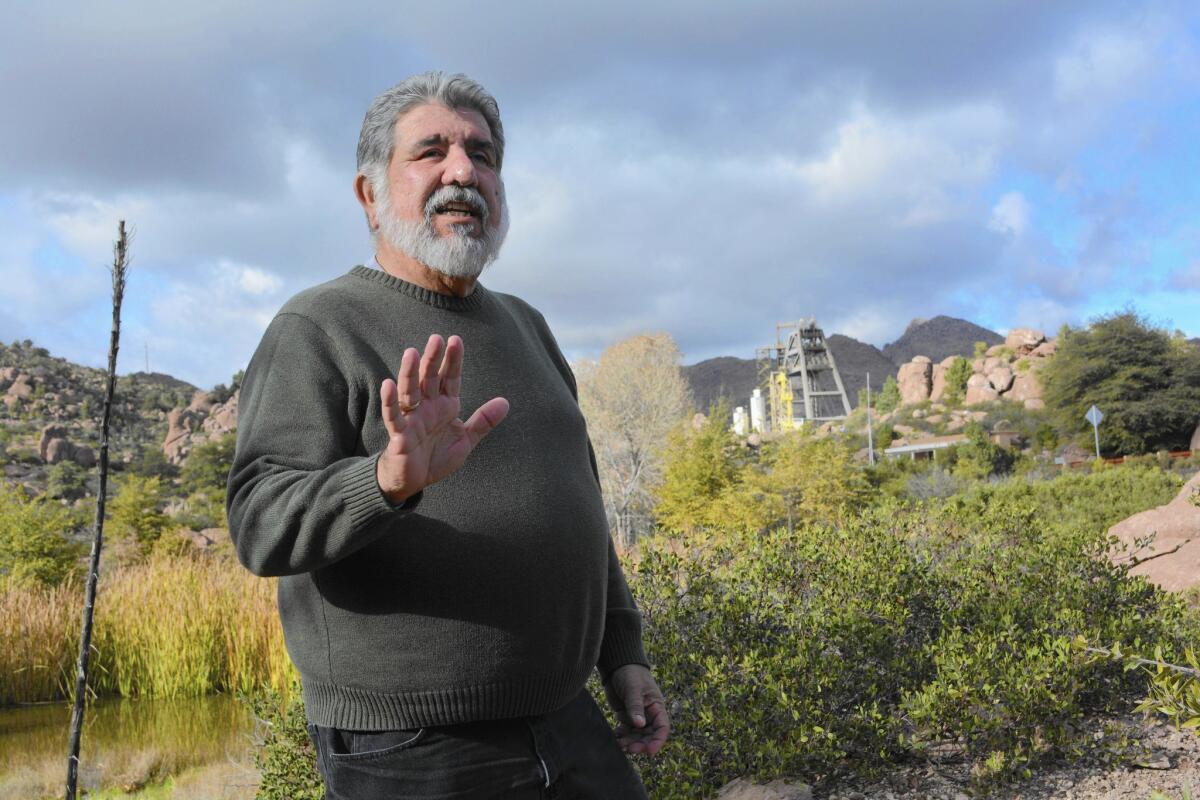

At the center of the debate is Roy Chavez, a former three-term mayor and self-proclaimed rabble-rouser who delights in driving around the crimson center of red-state Arizona in a pickup adorned with Barack Obama bumper stickers.

But if his political beliefs are deeply felt, he is practically evangelical when it comes to opposing the proposed mine.

“It’s just an evil project — environmentally and socioeconomically. The project is completely unimaginable,” said Chavez, who, with the conviction and practiced patience of the politician he once was, frequently approaches strangers with a handshake, a pamphlet and an argument against the mine.

Chavez’s family has been mining in Arizona for nearly 100 years, and he spent much of his life below ground, digging out copper from the ore bodies that ring Superior.

So he’s not opposed to mining, but he is against this mine, at this time, in this place.

“I support the industry,” Chavez said. “I just can’t support this project and the way they’re going about it.”

The area around Superior is breathtakingly gorgeous, with rock towers carved by erosion, paloverde trees and pines framed at dusk by pastel sunsets. It’s why the place has served as the backdrop for nearly a dozen Hollywood films. It’s also why, 60 years ago, President Eisenhower banned mining on 760 acres of federal land just outside town.

But after failing more than a dozen times over nearly 10 years to get Congress to lift the ban, Arizona’s congressional delegation got around that roadblock in December by inserting the land deal into a must-pass military spending bill.

The end run angered environmentalists and Native American groups who say the mine would destroy the environment and erase cultural and religious sites considered sacred by the Apache.

Much of that opposition focuses on how Resolution Copper plans to extract the ore, using a relatively new practice called “block cave” mining. Unlike open-pit mining, which extracts ore from above, block-cave mining captures ore from below.

Caverns are excavated underneath the ore and, through gravity or blasting, the ore body collapses and fills the caverns. The ore is then transported through tunnels to the surface.

But as the ore deposits collapse, the ground above subsides. Resolution Copper has conceded that working the area below Oak Flat, a rare desert riparian area four miles outside Superior, will create a crater more than 2 miles wide and 1,000 feet deep.

It will also produce more than 1.3 billion tons of mud-like waste tailings — basically dirt, often toxic, left over after the copper has been extracted.

The record of Resolution’s parent companies wasn’t exactly stellar coming into this project.

Environmental groups say Rio Tinto’s Bingham Canyon copper mine outside Salt Lake City is a source of major environmental contamination that has resulted in water pollution and damage to fish and wildlife habitat. And that was before an April 2013 landslide in which 165 million tons of earth slipped, triggering 16 small earthquakes and burying more than 100,000 gallons of diesel fuel, oil, coolant and grease as well as a container holding thousands of pounds of explosives.

Critics also take issue with claims that the expansion of the Resolution mine will save Superior, saying that much of the $1 billion in annual economic activity will benefit other communities because the vast majority of the 3,700 workers hired will be commuters.

Mining has always run in boom-and-bust cycles, and when the bust came to Superior — and it came three times between 1982 and 1996 — it was merciless, eliminating thousands of jobs, closing businesses and bankrupting families. The town’s only traffic light was unplugged. And the population shrank by nearly two-thirds to 2,800, about a quarter of whom live in poverty.

Resolution Copper takes issue with many of the doomsday scenarios.

“Yeah, mines dig deep holes. And they cause destruction. That’s true,” company spokesman Dave Richins said. But “you can do things that make it not as bad. These guys want to be the 21st century miners. They want to do it right.”

Copper, Richins said, is essential to the development of many renewal energy sources. And using the block-cave method to extract it is eco-friendly because given the depth of the ore body — 3,500 to 7,000 feet — a traditional open-pit mine would not be feasible and, if it were attempted, would cause far greater destruction.

The project could also significantly lessen the country’s dependence on foreign sources of copper, something the American Resources Policy Network, a public policy research organization, warns threatens the economy and national security.

The International Copper Study Group said worldwide demand for copper had exceeded supply in each of the last five years. Resolution Copper expects the mine to produce as much as a billion pounds of copper annually, about a quarter of the nation’s copper requirement.

“You’re going to see a tremendous boom in Superior,” Richins said. “The thing that is of advantage to us is the Copper Triangle has a lot of well-qualified, talented mining individuals that live there — from multiple generations. We want those people working at our mine.

“There’s not a lot of jobs in Superior now. We’ll change that.”

Before that happens, though, the mine must undergo a lengthy permitting process with the U.S. Forest Service as well as years of construction before any copper can be hauled to the surface.

In the meantime, Resolution Copper says the majority of residents in and around Superior are in favor of the project. Chavez and the mine’s opponents say the town is on their side.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.