Column One: Navajo shepherds cling to centuries-old tradition in a land where it refuses to rain

A brutal drought gripping the Southwest is hitting New Mexico and the Navajo reservation especially hard, threatening traditional shepherds and a pastoral way of life going back generations. (Katie Falkenberg / Los Angeles Times)

More than a hundred rowdy sheep pressed up against the gates of the corral as Irene Bennalley drew near. Dogs yipped, rams snorted.

Just after 7:30 a.m., she flung open the pen and the woolly mob charged out in a cloud of dust.

Well-trained dogs struggled to keep order as the flock moved across the bone-dry earth searching for stray bits of grass or leaves.

“Back! Back!” the 62-year-old Bennalley shouted at the stragglers separating from the flock — ripe pickings for coyotes or packs of wild dogs.

Thousands of clouds flecked the pale blue sky above.

“When I see all these thunderclouds gather I think, ‘Today it’s going to rain,’’’ Bennalley said wistfully. “And then, nothing.”

A brutal drought gripping the Southwest is hitting New Mexico and the Navajo Nation reservation especially hard, threatening traditional shepherds like Bennalley and a pastoral way of life going back generations. The Navajo are famous for rugs and blankets spun from the wool of their sheep. Many are works of art with intricate designs sought by collectors. Members of Bennalley’s Sleepy Rock Clan are accomplished weavers.

According to the National Drought Mitigation Center, nearly all of New Mexico is in severe or extreme drought, and San Juan County, where Bennalley lives, is suffering “exceptional drought” with little relief in sight. So far, winter has brought little snow.

“Drought is an extreme event and exceptional drought is the extreme end of that,” said Brian Fuchs, a climatologist at the drought mitigation center in Nebraska. “It’s not only a forage issue for livestock, but the water sources are drying up.”

In May, nearly 200 wild horses were found dead on the reservation, trapped in the mud of a dried-out watering hole.

As resources dwindle, some Navajo shepherds are selling their flocks or spending what little they have on hay to feed them.

“For many of these people, their sheep are like family. They will feed them before they feed themselves.”

— Jennifer Douglas, project manager for Investments in Resilience

“These sheep will go into fall and winter skinny and malnourished,” said Jennifer Douglas, project manager for Investments in Resilience, a group working with shepherds to lessen the effects of the drought. “I think we will have a lot of livestock deaths if we cannot continue to provide hay.”

Douglas, who is not Navajo, has tapped Bennalley to help her identify fellow shepherds who need help. So far she’s located about 85. Many are elderly, live in remote areas and are wary of outsiders. The group gives or sells them hay at a discount, about $16 to $18 a bale.

“I think the breaking point will come when drought creates a situation where the plants can’t come back and they can’t feed their sheep on the range,” Douglas said. “For many of these people, their sheep are like family. They will feed them before they feed themselves.”

As Bennalley’s sheep scrounged for food on a fall day, she walked slowly behind while wearing a broad-brimmed hat. While the sheep-herding dogs worked the flock, some of her other dogs followed — Sampson, White Man and tiny Ariel, about the size of a football. A towering volcanic plug stood in the distance, rumored to be a gathering spot for skin-walkers, malevolent witches who can assume the form of animals.

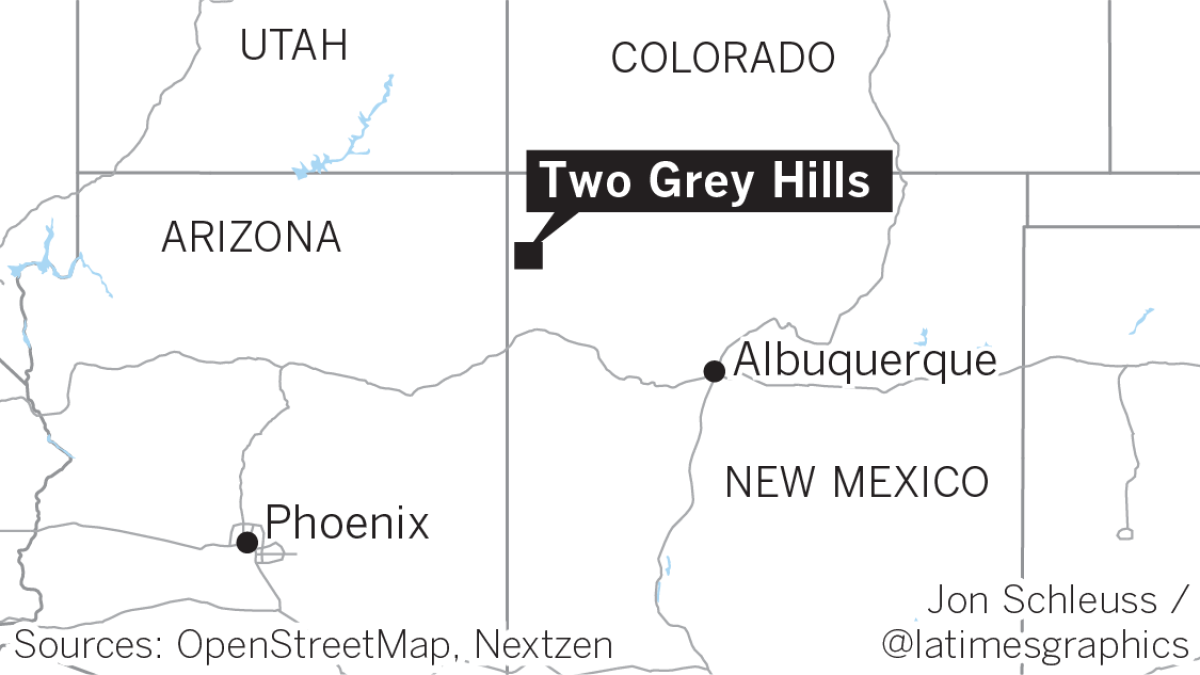

Bennalley was married for a time, then divorced. She flirted with the idea of becoming a veterinarian or joining the military. But she was drawn to the elemental life of a shepherd here in Two Grey Hills, an area renowned for producing some of the finest Navajo rugs in the world.

“I talk to myself a lot out here. If I am sad or hurt, I talk. But one thing I have never felt was loneliness,” she said. “I believe you are never alone. Mother Earth is here, Father Sky. I don’t need another human to not feel lonely. I have all these critters who keep me company.”

She won’t speak of the drought near her sheep, fearing they will sense her anxiety.

“I am their human and they trust me to take care of them,” she said. “I have to have faith in the Creator that this is happening for a reason.”

History says the Spaniards brought sheep here 500 years ago. But many Navajo, who call themselves Diné or Dineh (“the people”), believe they were here long before that, citing ancient songs and chants extolling the animals. Over the centuries, they have provided meat, milk, wool and companionship for residents of the Navajo Nation.

Sheep even figure in the annual Miss Navajo Nation pageant — contestants must slaughter, skin and clean a ewe in about an hour.

“The sheep are like our ancestors. We were taught, from the year zero to where we are now, that sheep is life,” said Ron Garnanez, 66, a shepherd and president of the board of the Navajo Lifeway, a group dedicated to preserving tribal sheep culture. “They are part of our prayers and ceremonies. They have sacred names and sacred chants. They are not just animals, they are our spiritual guardians.”

Bennalley sings sheep songs but politely declined to share one.

“My dad sang me the songs. That’s how they are passed down,” she said. “If the song wants you, you will be accepted by it. It will take you in. They cannot be exposed to everyone because they are sacred.”

Some shepherds raise breeds like Merino or Rambouillet, but Bennalley sticks to the Navajo-Churros, prized for their wool, meat and ability to survive. Like the shepherds, they are rugged and resilient. Churros, as they are often called, can go days without eating or drinking and can tolerate a wide range of temperatures. But they are not invincible.

In the 1930s, the U.S. government began a “livestock reduction plan” here, claiming overgrazing was causing soil erosion. Federal agents sold or shot hundreds of thousands of sheep and goats. The event traumatized the Navajo, who still tell stories of men gunning down sheep in their pens or stampeding them over cliffs. Their bones can still be found scattered across the reservation.

“It was the worst time in many peoples’ lives; it was a time of heartache,” Bennalley said. “We view sheep as part of our family, and here people saw them shot down and slaughtered right in front of them.”

By the mid-1970s, only a few hundred Churros remained. In 1977, Lyle McNeal, now a Utah State University professor, started the Navajo Sheep Project to revive the breed. There are several thousand on the reservation today, though their fate remains precarious.

“The drought means the animals used to breed or diversify are being eaten, sold or dying of starvation,” said Tara Roche, president of the Navajo Sheep Project. “That means that many shepherds have had to leave the reservation, and considering the role sheep play in the Navajo way of life, this is a travesty.”

While there are no hard numbers, Bennalley thinks perhaps 200 shepherds remain on the entire reservation, mostly in Arizona. Growing up, she recalls seeing hundreds of shepherds at communal “sheep dipping” events, in which the animals were doused in insecticide and fungicide to guard against pests.

“There were a lot of shepherds with flocks. Many families had sheep,” she said. “You don’t see that anymore.”

Bennalley has emerged as a leader among the remaining shepherds, fiercely committed to a fading way of life.

She lives in a two-room house with her son on a small ranch at the end of rough dirt road. It’s home to 21 dogs, uncounted cats, horses, alpacas, chickens, geese, a turkey named Tommy that lingers in her doorway, Chinchin, a winsome Angora goat playful as a puppy, and, of course, sheep.

As a girl, Bennalley, one of 12 children, would sit in the house and listen to her grandmother talk about the sheep, the land and the seasons.

“She was an herbalist and a shepherdess as well. If a sheep hurt itself she would use a medicine from the land to heal them,” she recalled. “She was slowly going blind, and she’d ask me what time of the season it was. Where is the moon? When does the sun rise? Have the aspens changed in the mountains?”

The land was different then, Bennalley said. There was green grass and it rained hard in the spring and summer. The mountains were wet, the ponds full of water. Winters were bitterly cold and snowy.

“I don’t want to think about this all ending. I am not going to let them die out.”

— Irene Bennalley

“When I was in high school and the snow was deep, I would drive the cattle over to the turnoff and back so I could have a clear way to walk to the bus stop,” she said.

A natural loner, Bennalley took to herding early. Her mother and father were shepherds. As a child, she named every sheep, took in orphaned lambs and cared for sick and injured animals.

At dinner her father would tell her how best to handle the flock. She often wishes she’d recorded him, but in times of difficulty his voice comes back to her with the right answer to her questions. Yet even he can’t make it rain.

Day after day, Bennalley drives her flock deeper and deeper into this parched land searching for increasingly rare shoots of grass.

Last summer, for the first time, she couldn’t take her sheep on the 13-mile trek into the cool Chuska Mountains.

“The grass was crunchy. There were no ponds. Everything was empty,” she said. “I said, ‘Oh man, what are we going to do?’ I don’t want to think about this all ending. I am not going to let them die out.”

But the drought has taken a toll on the reproductive health of her flock. She expected at least 30 lambs to be born this winter. Instead, she got nothing.

“I have to live with it and accept what’s there,” she said. “Hopefully, we can move into the hills next summer so they can get healthy again.”

She now spends much of her money on hay to sustain her animals — forgoing shoes, new clothes and tires for her truck.

She supplements her income by offering outsiders the chance to play shepherd. For about $350, they can spend three days helping her herd sheep into the mountains, which she couldn’t do this last year because of the drought.

“People want the experience, the connection to the land,” she said. “I had a lady come from Santa Fe who wanted to learn about sheep, another wanted to learn about weaving.”

Bennalley’s Sleepy Rock Clan even made it into Mark Winter’s “The Master Weavers,” a hefty book he spent 25 years compiling that features some of the best weavers on the reservation.

Winter runs the Toadlena Trading Post about five miles from Bennalley’s house. Back in the 1970s, he owned a small craft shop in Idyllwild, Calif. One day, a trader walked in with seven Navajo rugs.

“He left with all my money and ruined me for life,” Winter said, describing his subsequent infatuation with the textiles that led him here more than 20 years ago.

He showed off a crimson blanket worth about $100,000.

“At one time Navajo rugs were the most valuable trading items in the American Southwest,” he said.

He pays local weavers — those whose families are in the book — to make rugs for him to resell. Because good rugs take time, he often loans them money while they work.

“We pay rents, we pay bills,” he said. “We get involved in their lives in many ways. It’s kind of crazy, but it works.”

Back at Bennalley’s spread, the sheep were returning to their pen by midafternoon, spurred on by vigilant dogs. Pint-sized Ariel occasionally yapped at them as well.

The clouds had drifted off, failing again to deliver rain. The final sheep straggled in, weary and hot in their woolen coats. The horses and alpacas gathered near a fence to watch the return. A handful of cows turned up too.

Bennalley looked at all the animals looking back at her — their human.

Something caught her eye.

She bent down and examined a few green leaves on a shrub.

“See,” she said, “there is hope.”

Kelly is a special correspondent.

Produced by Agnus Dei Farrant.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.