These children of celebrity dads are taking their stepmoms to court

- Share via

Reporting from SEATTLE — When Catherine Falk asked to see her ailing father, her stepmother shut the door in her face. When Kerri Kasem arrived to take her dying father to a hospital, her stepmother met her in the driveway — and hurled raw hamburger at her.

The confrontations sparked headlines because the women’s fathers were well-known public figures — actor Peter Falk and legendary DJ Casey Kasem. Both died while costly family legal squabbles raged over the visitation rights of their daughters and other relatives.

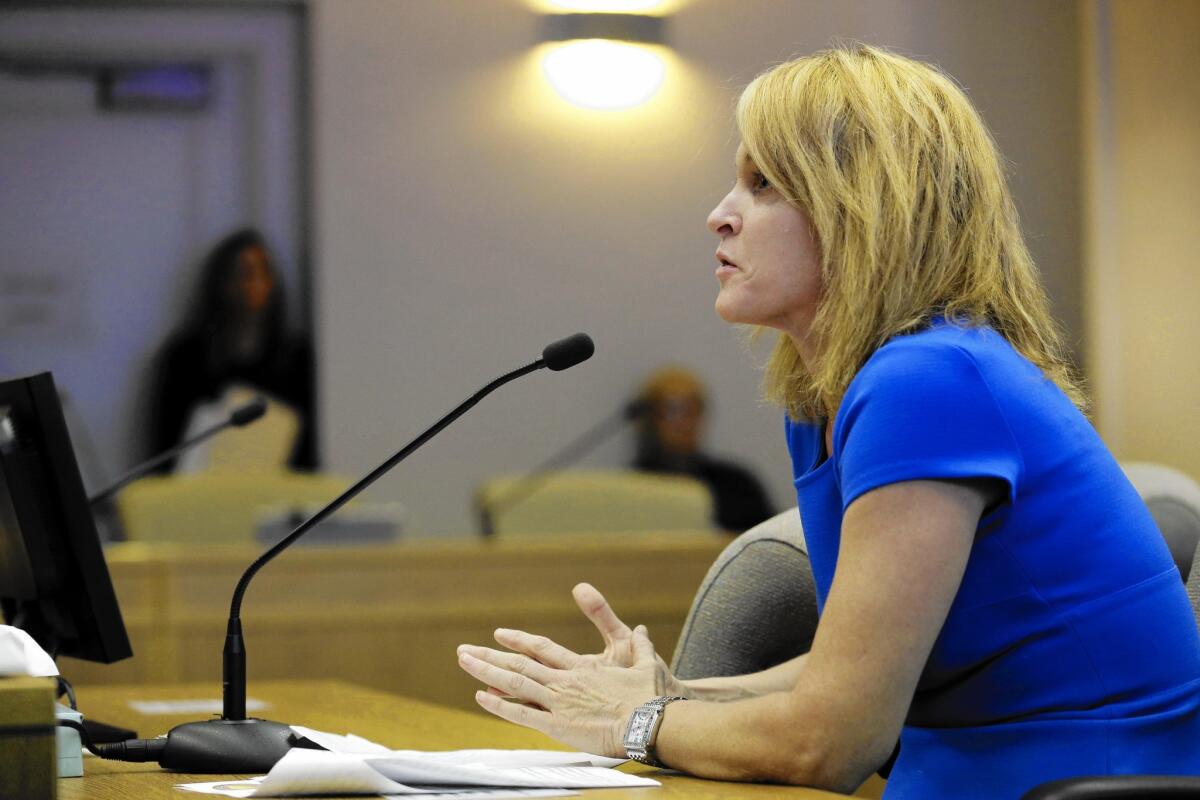

“It cost me $400,000 to see my father,” Kerri Kasem recalled recently as she rushed to catch a flight to New Mexico and testify before the Legislature in Santa Fe. Her Kasem Cares Foundation is backing a bill she said would make it easier for friends and relatives to visit ailing elders.

“I don’t want others to go through what we went through,” says Kasem, 43, “emotionally and financially.”

On the same day, Catherine Falk, 44, was heading to Utah and a legislative appearance to promote a similar visitation bill supported by the Catherine Falk Organization.

Though Falk and Kasem work independently, they’ve become a powerful one-two punch for reforming visitation laws, stumping for change in more than 30 states. Falk says her proposed legislation is now being considered in 10 states; Kasem’s bill has already been adopted in three — California, Iowa and Texas.

The two agree their efforts are getting notice because of their celebrity fathers, and have little problem with such an advantage. “This isn’t the Casey Kasem Bill, or the Mickey Rooney Bill, or the B.B. King Bill,” Kasem said, referring to other personalities who went through similar elder battles. “It’s the Visitation Rights Bill, and it affects thousands in the U.S.”

Kasem and Falk are contacted regularly by people with horror stories to share, such as the Colorado woman who described her mother’s common-law husband as an abusive alcoholic who prevented the rest of the family from seeing her, then beat her. The mother ended up in a rehab facility after a fall and the daughter was not allowed to visit. Not long after, the daughter learned her mother had died.

Though the coroner was called, she said, there was no autopsy and her mother’s body was cremated.

“I do not know where her remains are,” the woman said.

The Falk and Kasem bills focus on visitation rights and seek to provide intervention for seniors being physically or financially abused. The ultimate goal is a uniform federal law, since the bills vary state to state in language and differ in respect to guardianships.

California’s Legislature, for example, unanimously approved a Kasem-backed bill that enables courts to order conservators to allow phone calls, mail and visits from relatives. Previously, a long and costly fight was likely when adult children challenged a conservator who was forbidding family contact.

Though similar, Falk’s legislation sets legal standards for conservators, including a duty to inform relatives of a subject’s illness or death, and allows “reasonable visitation” access. Disputes would be resolved in a streamlined court process to determine whether such a visit would be harmful to the senior. Conservators could also be fined for failing to act.

Kasem said a key difference between the two bills is that Falk’s can require relatives to file guardianship petitions to enforce visitation rights. She argues that such a bill wouldn’t have helped either Falk or herself in their disputes. Both were forced to put their fathers into conservatorships so they could visit them.

But not everyone thinks the proposed laws are necessary, or even a good thing.

At a January legislative hearing on Kasem’s bill in Washington state, Megan Farr, an attorney representing the elder law section of the State Bar Assn., said the state had sufficient existing statutes to address isolation and abuse. And Steve Lindstrom, from the Washington Assn. of Professional Guardians, cautioned lawmakers not to “overly complicate what is already a fundamentally good law.”

Falk — adopted at birth by Peter and Alyce Falk, who divorced when she was 5 — had a strained relationship with her stepmother, who met Peter Falk on the set of his signature TV show, on which he played the absent-minded detective Columbo.

Falk said she was never notified when her father began suffering from advanced dementia, possibly related to Alzheimer’s disease, and then she was barred from visiting. When he died at the age of 83, she and her sister said they learned of his death from the media and were never informed when he was buried at Westwood Memorial Park.

The stepmother, Shera Danese Falk, said in court that she had taken proper care of her husband as his appointed caregiver, with nurses subbing for her around the clock when she was away. She argued that Peter Falk had a strained relationship with his daughter dating back to a 1992 lawsuit when she demanded her father pay her college expenses, as required by his divorcee agreement with Alyce Falk. Catherine admitted they had a falling out over the suit but had since reconciled.

Kasem’s situation was extreme enough that it made headlines.

Her father, the legendary DJ and longtime “American Top 40” host, was removed from a Santa Monica hospital in 2014 by second wife Jean Kasem, an actress who had a small role in the TV comedy “Cheers.” Disconnected from a feeding tube and barely able to walk or speak, Casey Kasem was taken to Las Vegas, then to Washington state and a hospital in Gig Harbor, near Tacoma. There, at age 82, he died from complications of Lewy body dementia, similar to Parkinson’s.

That followed a drawn-out legal challenge and an odd encounter at a home in Port Orchard, Wash., where Casey Kasem had been taken. Kerri Kasem said when she arrived with an ambulance and court order to see her father and take him for a welfare check, Jean Kasem threw a pound of wrapped, uncooked hamburger at her, according to court records. “In the name of King David,” Jean reportedly yelled. “I threw a piece of raw meat into the street in exchange for my husband to the wild rabid dogs.”

Later, Jean Kasem reportedly flew the celebrated DJ’s body to Canada and then Norway, where he was buried — the end of an eight-month, 8,000-mile odyssey.

The Los Angeles district attorney’s office investigated Jean Kasem for neglect and elder abuse, but concluded there wasn’t enough evidence to support criminal charges. Deputy Dist. Atty. Belle Chen stated in a memo that Jean Kasem had made “continuous efforts to ensure that Mr. Kasem was medically supervised.” Relocating him to Washington was an effort to protect his privacy, Chen said.

Peter Falk and Casey Kasem are remembered by stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. But their daughters are hoping for a more lasting tribute — 50 new state laws in their honor.

“What happened was wrong,” said Catherine Falk, “but that would help make it right.”

Anderson is a special correspondent based in Seattle.

ALSO

In the Iditarod, climate change makes it a year for the record books

In a reversal, Ferguson City Council agrees to reforms and federal oversight

13.1 million U.S. coastal residents could face flooding from rising sea levels, study says

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.