This is where the Grammys are born — in a remote mountain workshop in Colorado

- Share via

Reporting from RIDGWAY, Colo. — Few places feel more removed from the glamorous world of the entertainment industry than this remote town high in the San Juan Mountains.

It’s an almost magical land of tumbling trout streams, turquoise lakes and craggy peaks.

For the record:

4:15 p.m. Nov. 27, 2017An earlier version of this article said Billings works five days a week on the Grammys. He says he works seven days a week.

It’s also the home of the Grammy Awards.

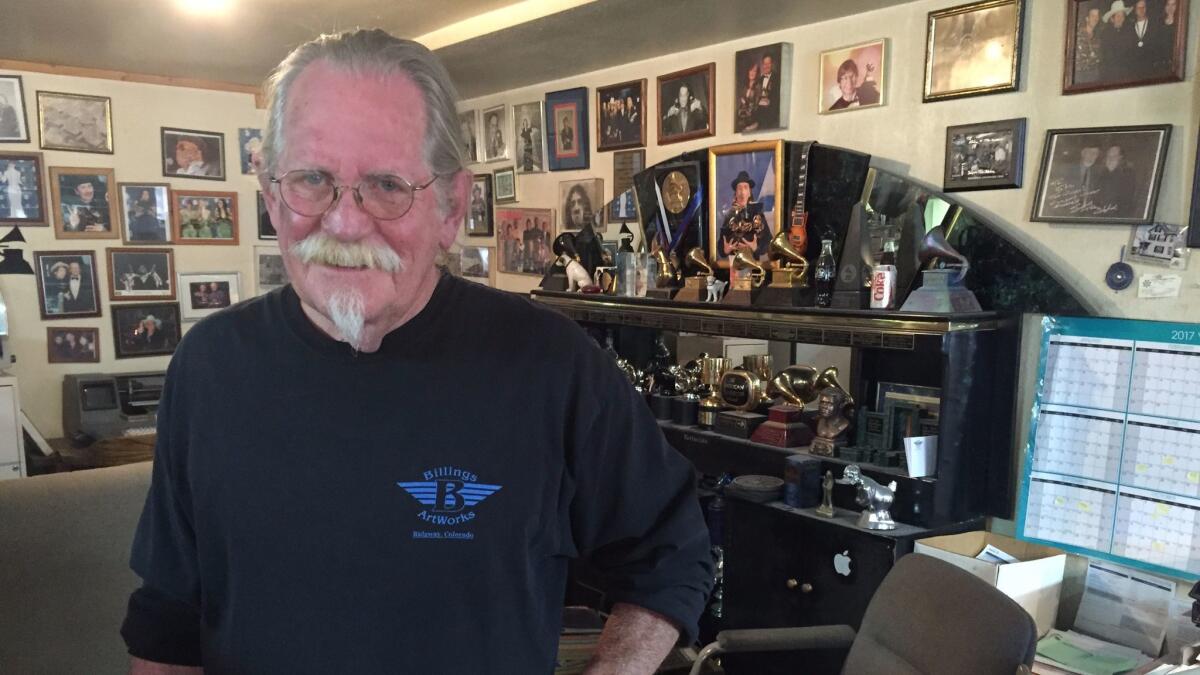

In a small workshop here, John Billings and his team of three craftsmen cast, hammer, polish and assemble each of the little gold gramophones. There are no robots, no assembly lines. Just century-old hammers, files and endless patience.

Billings, 71, has been making the Grammys for 41 of the awards’ 60 years, including the upcoming awards show. His workshop will produce 350, along with about 220 Latin Grammys, for the upcoming show on Jan. 28. Each one takes 15 hours to make.

When finished, they’re put into a trailer and driven to Los Angeles. Once there, Billings picks up a load of his signature “grammium,” a secret zinc alloy used to make the awards that is smelted in suburban Los Angeles. Then it’s back to southwest Colorado to start all over again.

It might seem surprising that the Recording Academy, which hands out the Grammys, would rely on four guys in a 2,000-square-foot mountain workshop for its most prestigious award.

Oscar statuettes are made by a New York company whose website says its main studio bay “is as big as a football field and four stories high.” The Primetime, Daytime and Sports Emmys are made in an 82,000-square-foot facility in Chicago.

“I guess it’s not really our style to go with the easiest way of doing things,” said Bill Freimuth, senior vice president of awards for the Recording Academy. “One of the reasons artists appreciate the award is because it is handmade and handcrafted by other artists. Some would argue that it’s more precious because of that.”

Billings, known locally as the Grammy Man, would certainly agree.

“Every Grammy we make is an individual,” he said.

And like individuals, imperfections can arise.

“We’ll ask each other, ‘Is it a flaw or does it give it character?’ ’’ Billings said. “If it’s flawed we toss it, the others we keep.”

On a recent Saturday, Billings sat in a shadowy room surrounded by old or broken Grammys – one serving as a paperweight -- doing the Los Angeles Times crossword puzzle. The place was quiet. A picture of musician Carlos Santana holding a stack of Grammys looked down from the mantel.

Billings was born in Santa Monica and, as a child, lived in the Rodger Young Village in Griffith Park, a temporary public housing project set up for returning veterans after World War II. “I used to go to bed and listen to the animals in the L.A. Zoo,” he said, lighting a cigarette.

The family later moved to Van Nuys, next door to Bob Graves, who cast the original Grammy mold inside his garage in 1958. The awards were presented to artists at the first ceremony in 1959 for work done the year before.

Billings watched Graves work and swiftly fell in love with the process. He became a self-taught silversmith and later earned a degree in dental technology, learning to make false teeth.

“Casting teeth and jewelry uses essentially the same technique,” he said.

Billings credited his older brother Don for his own painstaking attention to detail.

“He was deaf and in those days people shied away from deaf people, so he’d spend hours in his room building model airplanes,” he said. “He taught me patience.”

Graves offered Billings an apprenticeship in 1976 to help him make the Grammys and other molds. In 1983, after Graves died, Billings bought the business from his widow.

During the early 1990s, Grammy executives asked Billings to redesign the award so it looked bigger on television and was less fragile. The tone arm attached to the gramophone bell broke easily. Billings made it thicker and replaced the walnut base with a metal one. He increased the overall size of the trophy by about 30%.

The final product weighed in at 5 pounds.

Business was good but Billings was weary of the frenetic pace of Los Angeles. He yearned to escape and in 1993 got his chance.

The late actor Dennis Weaver, star of the television show “McCloud,” hired him to make the light fixtures for his home in Ridgway. The town, with a population of about 1,000, has a park named after Weaver.

“I had never been to Colorado and I went ‘whoa!’ ’’ Billings recalled. “It reminded me of Van Nuys in the ‘50s when it had bean fields, orchards and dirt roads. I told my wife that this was the place we were going to live. She didn’t object.”

He bought a house beside a river where he regularly fly fishes. Now he works seven days a week making Grammys, along with other products, including the John R. Wooden Awards given to the most outstanding men and women’s college basketball players.

Billings, an easy-going man with a gray ponytail, snuffed his cigarette and walked into the workshop behind his office. A sign above read “Grammy Row.” It felt like a time capsule. Dusty statues of ballerinas, old clocks and vintage gramophones sat on the shelves.

There were bundles of iron files in cups, scorched ladles for hot metal and a 120-year-old “chasing” hammer with a flat head used to make grooves on the Grammy.

A Grammy Award is made of a base, a cabinet and a tone arm that holds the bell. Each part is cast from a mold, filed and polished. Then they are assembled and plated in 24-karat gold.

On the night of the awards, winners are handed what Billings calls “stunt Grammys,” not the final product. Billings later gets the names of the winners and engraves each one on the award.

He usually attends the Grammys show and nominee party as well. He plays bass and enjoys the company of musicians.

“I’ll never forget watching Jack Nicholson giving Bob Dylan – and I’m a huge Dylan fan – the Lifetime Achievement Award,” he said. “I started to cry because I made it and felt I was part of it.”

The awards are sturdy but not indestructible. In February, singer Adele snapped off part of her Grammy on stage. In 2010, Taylor Swift dropped one of the four Grammys she was cradling, breaking it into pieces. She wrote ‘Oops’ on the side and it now sits in Billings’ office.

“If they break it we will repair it,” he said. “We also refurbish old Grammys. I did one for Ella Fitzgerald.”

But the Grammys aren’t his top moneymaker, he said. That honor goes to a nickel-plated, cigar-smoking duck he made for the 1978 movie “Convoy” about an armada of truckers who confront a crooked Arizona sheriff.

Kris Kristofferson starred in the movie, going by the CB radio handle “Rubber Duck.” The metal duck was his hood ornament.

“Convoy” was based on the song by C.W. McCall, former mayor of nearby Ouray, Colo., and a friend of Billings. Producer Quentin Tarantino used the same duck in his 2007 movie “Death Proof.”

“My son said we ought to sell those ducks on eBay,” Billings said. “The phone began immediately ringing off the hook. They have become the holy grail, the Maltese Falcon for truckers to obtain.”

Billings recently hired another craftsman to work solely on the ducks.

The “Death Proof Duck” sells for about $185 each. The Grammys aren’t for sale and Billings declined to say what they might be worth.

Yet he’s already paid a steep price.

His hands are battered from a lifetime of molding. His hearing has suffered from the constant hammering. His arms are covered in burns from scalding metal and his back isn’t what it used to be.

But Billings is holding to a promise.

“When Bob Graves lay in the hospital he said, ‘I want you to promise me you will keep doing the Grammys and won’t let anyone else get them,’ ’’ Billings recalled. “I said I would and I’m trying to hang on as long as possible.”

To read the article in Spanish, click here

ALSO

The Grammy nominations could embrace diversity. Expect lots of Ed Sheeran

Forget Carnegie Hall. Musicians rush to rural Colorado to play the Tank

Kelly is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.