Q&A: Trump ended separating families. But what’s next?

- Share via

President Trump has signed an executive order ending the administration’s practice of separating immigrant families, but many issues concerning immigration remain up in the air. Among the key questions still pending: What happens to more than 2,300 children still in custody and away from their parents?

Here’s a guide to key questions on immigration:

Does President Trump’s executive order mean all immigrant families who arrive at the border will no longer be separated?

Not entirely. While the order said that it is “the policy of this administration to maintain family unity,” it also said the Trump administration plans to do so “by detaining alien families together where appropriate and consistent with law and available resources.”

The order also directed the Homeland Security secretary to house families together “to the extent permitted by law and subject to the availability of appropriations.” That leaves the possibility that immigration officials could still separate families because of space constraints at Border Patrol processing centers where they are initially held, and at Immigration and Customs Enforcement family detention centers where they stay longer term.

Border Patrol officials have long reserved the right to separate families when they fear adults could pose a danger to children, and the order emphasized that remains the case.

“As specified in the order, families will not be detained together when doing so would pose a risk to the child’s welfare,” Border Patrol officials said in a statement Thursday, adding that “family units may be separated due to humanitarian, health and safety, or criminal history.”

Will immigrants still be charged in federal criminal court?

Yes. Trump’s order made clear that Atty. Gen. Jeff Sessions’ “zero tolerance” policy, which officials also refer to as “100% prosecutions,” remains in effect. Under that policy, piloted last year along western sections of the U.S.-Mexico border and expanded borderwide in April, immigrants who cross into the U.S. illegally are charged in federal criminal court before their cases reach administrative immigration court. Those who crossed for the first time are charged with a misdemeanor and second-time crossers with a felony that carries a potential two-year prison sentence. The charges make it easier to deport people due to their criminal record, and the potential sentence is intended to serve as a deterrent to other immigrants.

“Border Patrol will continue to refer for prosecution adults who cross the border illegally,” the agency statement said.

Some parents saw federal criminal charges dropped Thursday, but it wasn’t clear whether that was a fluke or a policy change.

In McAllen, Texas, 17 parents who appeared for sentencing had misdemeanor illegal entry charges dropped, according to a federal public defender and attorneys at the Texas Civil Rights Project.

Spokesmen for the Homeland Security Department and the Justice Department said “zero tolerance” was still in effect. Katie Shepherd, national advocacy counsel for the Immigration Justice Campaign, said that appeared to be the case.

“Our understanding is that prosecutions will continue,” she said. “Hopefully it won’t mean that the families are still being separated.”

What has been the effect of the ‘zero tolerance’ policy?

The policy has flooded federal courtrooms along the border and overwhelmed federal public defenders, particularly in the Rio Grande Valley in southern Texas, where most immigrants cross. In the southern district of Texas, caseloads have doubled from two months ago.

Federal criminal prosecutions of migrants increased 30% nationwide from March to April, according to a database at Syracuse University. The data showed that about 60% of federal criminal prosecutions in April were for immigration violations.

How are unaccompanied children handled?

By law, children must be turned over within 72 hours to the Department of Health and Human Services, which transfers them to a series of 100 shelters in 17 states. Then the department’s Office of Refugee Resettlement attempts to place the children with relatives or other sponsors, sometimes in federal foster care. Those already separated will continue to move through that process, officials said.

What happens to the 2,300 children already separated from their parents?

“For those children still in Border Patrol custody, we are reuniting them with parents or legal guardians returned to Border Patrol custody following prosecution,” the agency said.

They will remain separated for the moment.

"It is still very early and we are awaiting further guidance on the matter. Our focus is on continuing to provide quality services and care to the minors in HHS/ORR funded facilities and reunifying minors with a relative or appropriate sponsor as we have done since HHS inherited the program,” said Brian Marriott, a spokesman. He added that reuniting families remains “the ultimate goal.” How that will happen, however, is unclear.

Attorneys representing detained immigrant children released a statement Thursday condemning the lack of a plan to reunify families. The attorneys noted many of the children’s parents have already been deported, making reunification difficult. They also will seek a court order to block the deportation of parents until they have been reunited with their children.

“This entire episode has been a disaster for the well-being and safety of thousands of innocent children and must come to an immediate end with remedial steps being taken to undo the extreme harm caused by the mass separation of young children from their parents,” they wrote.

Will families be detained together instead of separated? Where will they be held, and is there enough space?

There are three family detention centers nationwide, two in south Texas, one in Berks, Pa. The Berks facility, designed to house men with children, can only hold about 100 people, advocates said. The Texas facilities can house several thousand immigrants. ICE officials don’t say how much bed space they have at family detention centers, but their capacity was listed as 3,326 in an April report by the Government Accountability Office. As of Thursday, there were 589 people held at Karnes, 1,978 at Dilley and 56 at Berks.

Katy Murdza, advocacy coordinator for the Dilley Pro Bono Project, noted that housing families can be difficult, since ICE houses men and women separately, as well as children of certain ages. This year, ICE has detained more pregnant women and those with small children than in the past, she said. On Thursday, officials announced that the military was preparing to house up to 20,000 migrant children on military bases, but those will largely be youth who arrived at the border unaccompanied by adults.

Has the ‘zero tolerance’ policy slowed the flow of families to the U.S.?

Apparently not, though it’s still early to discern a trend. As of May, 59,113 family members have crossed the border, on pace to exceed last year, because a surge of immigrants usually occurs during the summer.

Immigrant advocates question how the government will be able to accommodate so many families.

“They’re not going to be able to put everyone coming in family detention,” Murdza said. “They’d have to build new detention centers or convert.”

The Dilley and Karnes centers opened in 2014, after a surge of Central American families and unaccompanied youth at the border led the Obama administration to expand family detention, erect temporary holding facilities for youth at military bases and expedite deportations with immigration court “rocket dockets.” At Dilley, there’s an immigration courtroom in a trailer, but adults and children are not provided public defenders, relying instead on Murdza and volunteer attorneys.

“They can’t be speeding people through just to deport them, not giving people time to speak to an attorney,” Murdza said. “People have to be able to fight their case.”

How long can families be detained?

Under the 1997 court settlement that governs conditions for detained youth, they cannot be held for more than 20 days by court order, and must be kept in the “least restrictive” environment. Trump alluded to the settlement, known as the Flores agreement, in his executive court order.

Trump’s order also directs the Justice Department to file a request with the Los Angeles federal court handling Flores, which they did Thursday, asking to remove the 20-day cap, state licensing requirements and other restrictions that could slow expansion of family detention.

Trump’s order also directed Sessions to “prioritize the adjudication of cases involving detained families,” meaning they may be handled more quickly.

Attorneys representing immigrant youth under the Flores settlement noted that it “has largely been honored by every administration for over 20 years” and that it requires “the humane treatment of detained children and their prompt release from custody unless they are a flight risk, a danger to themselves or others, or a parent with whom they are detained does not want their child released without the parent also being released.”

How did the Flores agreement come about?

The cap was established by a judge in 2016 after immigrant parents — some of whom were held for years — mounted strikes and legal challenges. While some families are still held more than 20 days, perhaps due to difficulty finding a translator, most are held slightly less than 20 days, Murdza said. But she said the executive order “could mean a return to an Artesia-like situation in 2014 with people just detained for long periods of time, regression where kids are needing to be carried, depressed, wetting the bed, not eating. People get so desperate, they just want to get out of there.”

Did the executive order address asylum-seeking families who try to enter the U.S. at border bridges?

Not directly. The order noted that, “Under our laws, the only legal way for an alien to enter this country is at a designated port of entry at an appropriate time.” In recent weeks, scores of families have camped out on border bridges attempting to apply for asylum. Many were told by U.S. immigration officials that they could not enter the country due to space constraints in holding areas where they would be processed.

Advocates condemned the practice, insisting it is illegal to turn away asylum seekers. More recently, Mexican authorities have begun screening those entering the bridges, preventing families from entering.

Are any migrants who cross the border illegally with children getting released?

Yes. The Texas Civil Rights Group said misdemeanor charges against 17 adult immigrants were unexpectedly dropped. The 17 were to have been sentenced at the McAllen courthouse and it’s unclear why the charges were dropped.

Also Thursday, a group of clergy led by the Rev. Al Sharpton visited immigrant families that had been released. The clergy met them at a Catholic Charities respite center in McAllen, Texas. On Wednesday, more than 50 family members gathered at the respite center to eat hot soup, change into clean clothes and let their children play with toys arrayed in a corner. They would soon board buses to destinations across the country.

Sister Norma Pimentel, who runs the shelter, called Trump's order "a step in the right direction." "The whole zero-tolerance policy is not helpful," she said, but "it looks like we are going back to full [family] detention again." Pimentel said families also suffer in detention and that family detention centers are crowded. "Let's move forward with something that is truly a humane response to immigration," she said.

Most of the parents at the respite center were Central American, with children under age 5. Rio Grande Border Patrol Chief Manuel Padilla said last week that agents were not separating families with children under age 5.

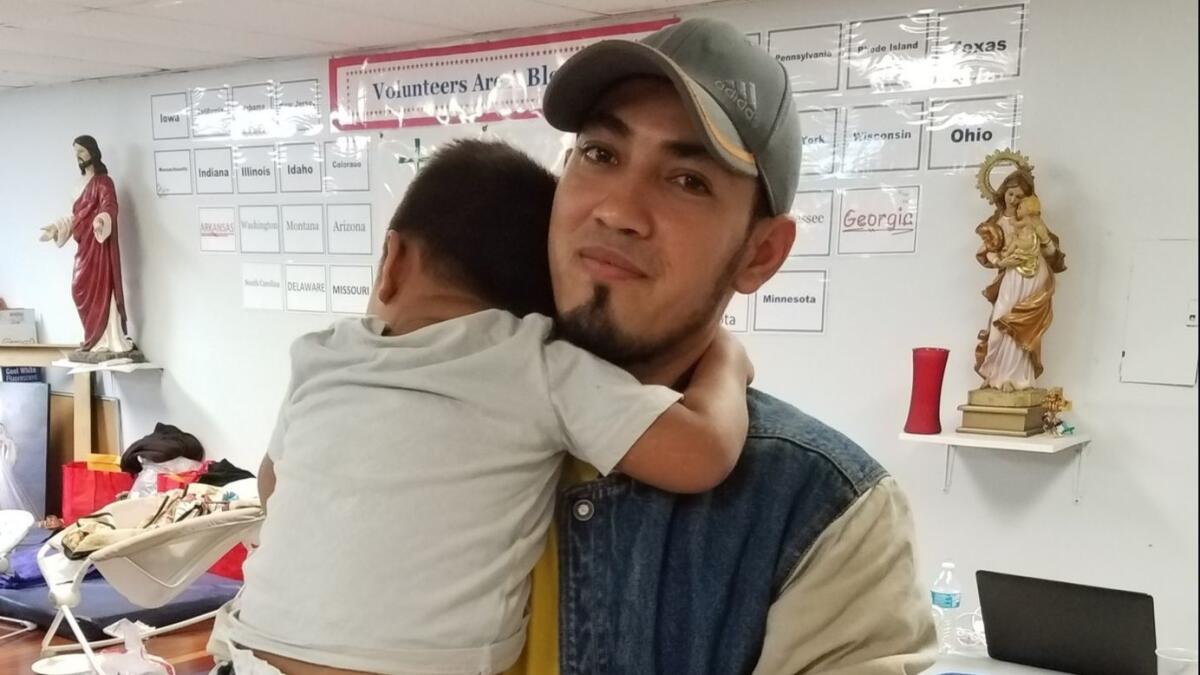

The families released Wednesday all had ankle monitors and orders to appear in immigration court. Among them was Alex Meraz, a welder from Honduras with a 2-year-old son, Jeremy. Meraz, 28, said he was unaware of zero tolerance and family separations when he left his wife and 5-year-old daughter about two weeks ago. It was his first time crossing the border illegally, but he was not charged in federal court or sent to family detention. He didn't know why.

At the Border Patrol processing center in McAllen, Meraz and his son were held in a chain-link-fence cell with other men and boys, and could see women and children in nearby cells. After three days, Meraz was bound for Boston to join a friend who had promised to help him find work. But he said he can’t forget seeing families torn apart. “I saw a [Honduran] woman crying because she said she was separated from her 5-year-old daughter,” he said. “Separating parents and children is ugly.”

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.