Before Zika: How the U.S. fought illnesses from pests in the past

- Share via

It’s not the fog of war, but it’s a war on bugs. And sometimes it’s fought with, well, fog. Recent efforts to halt the spread of the Zika virus in Florida bring to mind other times authorities have unleashed billowing clouds to combat pests.

DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane)

In the 1940s, DDT was developed as what the Environmental Protection Agency calls the “first of the modern synthetic insecticides.” It was initially used to protect against malaria and typhus, among other diseases transmitted to humans by insects.

DDT was effective against a variety of insects and quickly became popular among U.S. farmers. DDT also was used in livestock production and sprayed in gardens, institutions and homes.

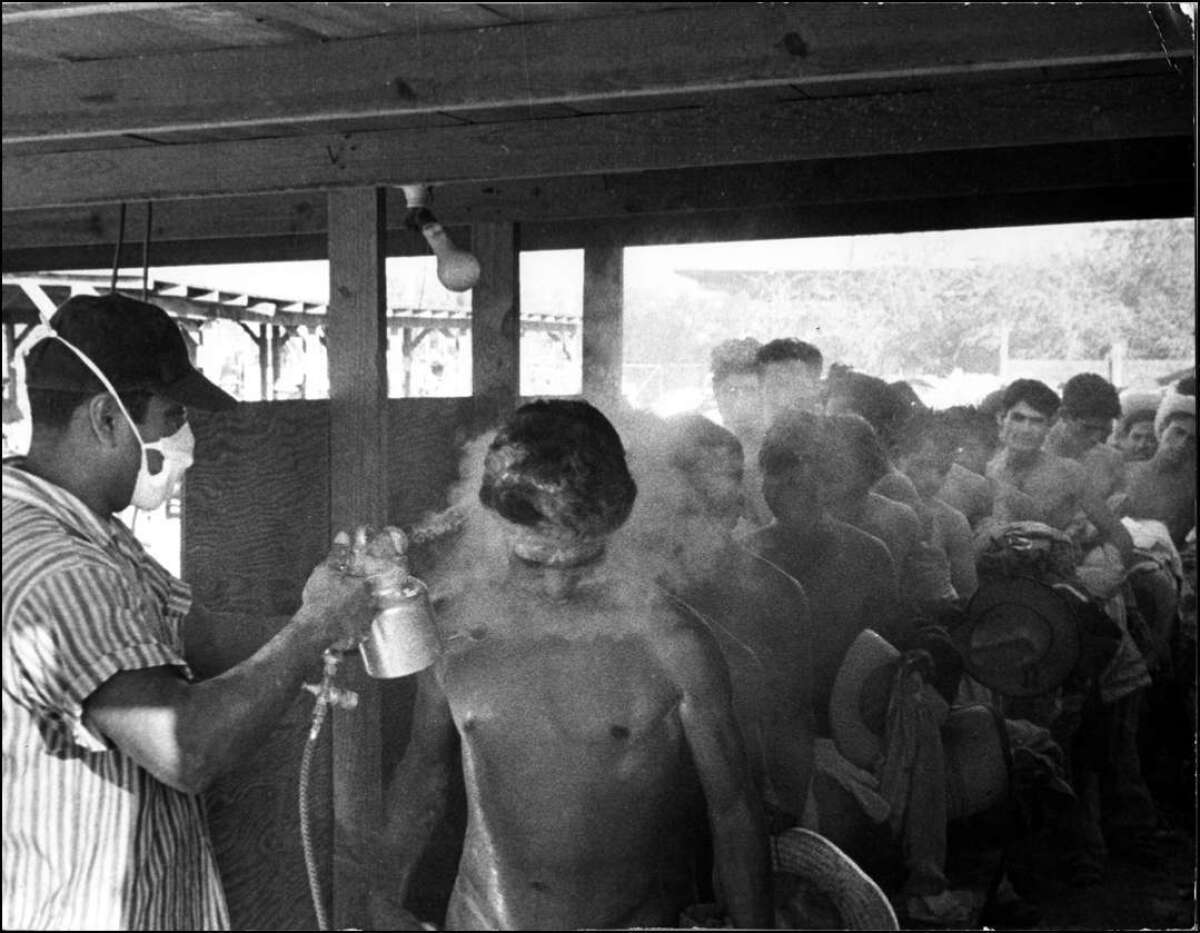

Migrant workers arriving from Mexico for seasonal farm work were sprayed thoroughly with DDT. Millions of workers arrived in the U.S. under the Bracero Program from 1942 to 1964.

Attitudes toward DDT changed in 1962, with the publication of Rachel Carson’s ground-breaking book, “Silent Spring,” which spread public concern about the dangers of pesticide use.

DDT was eventually suspected of causing a serious decline in the population of brown pelicans. As a result of chemical deficiency, female pelicans produced egg shells that were so thin most of them would break before the embryos could mature.

In 1972, the EPA banned DDT in the U.S. for its negative environmental effects and its potential risks to human health.

The pesticide is considered a possible human carcinogen, according to the Centers for Disease Control; studies on animals showed they developed liver tumors after ingesting large doses of DDT.

Malathion sprayed over Southern California

The insecticide malathion was registered for use in the U.S. in 1956 for agriculture, gardens and public recreation areas.

It’s still widely used in combating mosquitoes. Usually, it is released from trucks or helicopters and ejected in a ultra-low volume spray that stays in the air longer and kills mosquitoes on contact.

In Southern California, “malathion” became a familiar word — and a source of controversy — in the 1990s, when it was sprayed from helicopters to battle the Mediterranean fruit fly, which officials viewed as a major threat to California agriculture.

In 1990, the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services began experiments on child volunteers, applying small amounts of malathion to their skin to test possible allergic responses in humans. The study was approved by a scientific panel from UCLA with the permission of the children’s parents.

The results of urine analysis tests found no traces of malathion in any of the 67 samples, but samples from 12 children did show substances that form when malathion is metabolized in the body.

A report in 1991 based on those studied said that malathion spraying posed no serious threat to a “majority” of residents but did acknowledge that, in certain circumstances, some people could suffer from rashes, hives or other allergic symptoms.

Though the EPA says malathion poses no serious risks to human health, it does warn against contact with high doses. Malathion can overstimulate the nervous system, inducing nausea, dizziness or confusion.

In 1994 malathion was sprayed over 32,400 homes in Los Angeles County. That same year, during a series of aerial sprayings in Corona from February to May, about 250 residents reported skin rashes, allergic reactions and other symptoms.

Fighting Zika from the ground and the air

After authorities confirmed instances of locally transmitted Zika in Miami, crews descended on the city’s Wynwood neighborhood in July to unleash clouds of insecticide.

The infections were of special concern because it appeared the virus was transferred by mosquitoes in Florida. Previously, Zika infections reported in the U.S. had occurred only among people who had traveled abroad.

The type of pesticide released has been varied to prevent mosquitoes from building a resistance to the chemicals. The application methods also vary. One insecticide, Duet, is sprayed through a handheld portable backpack on the ground, while other pesticides, such as deltamethrin and Biomist, are released from equipment mounted on trucks.

Aerial sprayings of a pesticide called naled began on Aug. 4 to exterminate adult mosquitoes.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention urged people to stay away while naled was being sprayed.

A “large portion” of the mosquitoes carrying the Zika virus were killed during the initial sprayings in Wynwood, Dr. Thomas R. Frieden, the CDC director, said at a news conference.

Naled was registered for use in the U.S. in 1959 and is primarily released to control adult mosquitoes. The insecticide is also used on food and feed crops for animals and in greenhouses.

It doesn’t pose “an unreasonable” risk to human health, animals or the environment, according to the EPA. The agency found that spraying causes exposure hundreds or thousands of times below an amount that might pose a health concern.

On Aug. 5, Miami-Dade County officials authorized the use of a second chemical, VectoBac WDG, for aerial sprayings. The chemical is used to kill mosquito larvae. It is alternated with naled.

Twitter: @alexiafedz

MORE ON ZIKA

Opinion: Where are the funds for the Zika fight?

Brazil defeated the mosquito that spreads Zika once before — few expect it to do so again

Two babies in California born with microcephaly from Zika, officials say

When it comes to raising a child disabled by Zika, Brazilian women often do it alone

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.