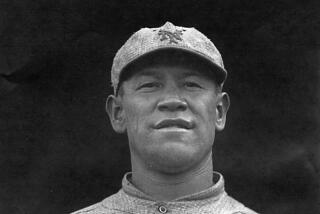

Battle for a famed athlete’s remains

- Share via

It was a sweat lodge ceremony in Texas where Jim Thorpe reached out to his grandson through a medicine man.

The shaman told John Thorpe that his grandfather’s spirit was content in the Pennsylvania town where his body has lain for six decades.

“Grandpa made contact with him and told him that he was at peace and wanted no more upset connected to him,” John Thorpe said.

That was nearly three years ago — shortly after one of Jim Thorpe’s sons, Jack, filed a lawsuit against the eastern Pennsylvania borough named after the legendary Native American athlete. The suit seeks the return of Thorpe’s remains to tribal lands in his native Oklahoma.

Since then, the case has forced Jim Thorpe residents to confront the prospect of losing their community’s namesake and widened a rift between his descendants, who disagreed on where Thorpe’s remains should rest.

“Moving him out of Jim Thorpe, a town that loves and honors and respects him and throws a birthday party for him every year, is just wrong, plain wrong,” said John Thorpe, whose mother, Charlotte, was a daughter from Thorpe’s first marriage.

In April, a federal judge sided with Thorpe’s sons William and Richard, who carried on the suit after their brother Jack’s death, and the Sac and Fox Nation of Oklahoma, the tribe to which Jim Thorpe belonged. The judge’s ruling requires the Pennsylvania borough of about 4,800 residents to begin the process of returning Thorpe’s remains.

At the center of the dispute is a federal law designed to end the plunder of Native American burial sites and give Native Americans control of their own people’s remains. Called the Native American Grave Protection and Repatriation Act, the law allowed the return of thousands of bodies and artifacts that were removed and added to museum collections beginning in the 1800s.

And, observers say, the interpretation of the law in the Jim Thorpe case has the potential to influence cases across the country.

Jim Thorpe borough leaders filed a notice on May 17 saying that they would appeal the decision by U.S. District Judge A. Richard Caputo.

Experts say that — as well-meaning as the borough’s residents were when they agreed to build a mausoleum for the two-time Olympic gold medalist and professional football pioneer — the town’s possession of Thorpe’s body is the kind of exploitation the law was intended to prevent.

“I don’t think that just because a person achieves national renown and respect means that his body can be the subject of commercial disputes and treated as a piece of property on his death,” said Walter Echo-Hawk, a Pawnee lawyer who helped draft the 1990 law.

Echo-Hawk said the Repatriation Act is a human rights law intended to correct a double standard in American society that allowed the desecration of Native American graves — acts that would be criminal if they involved nonnative remains — to go unpunished.

“There was an awful lot of bartering and trafficking in human remains that was going on. People selling skulls and pottery and things that were taken out of graves — just the kind of plundering that would shock the consciousness,” Echo-Hawk said.

In addition to criminal penalties for trafficking in Native American remains, funerary objects and cultural items, the law gives Native Americans a right to have remains returned when they are excavated or discovered on federal or tribal lands.

It also gives the right of repatriation, with priority to the closest living descendants, for remains and cultural items that are in museums or controlled by federal agencies.

This provision gave rise to the central controversy in the lawsuit by Thorpe’s sons against the borough of Jim Thorpe.

The Repatriation Act defines a museum as any institution or government agency that has received federal funds since the law was passed in 1990.

Lawyers for the borough argued that although Jim Thorpe had benefited from federal grants, it didn’t qualify as a museum because it didn’t receive the money directly. Rather, the money passed through the state or county government before being doled out for infrastructure improvements in the borough, the lawyers argued.

In his decision, Caputo examined cases that deal with the question of when receiving federal funding makes an institution or corporation subject to federal laws.

Based on evidence that the borough, in two examples, had received federal money for water meter replacement and flood control projects, it was subject to the Repatriation Act.

One expert, however, questioned whether the Repatriation Act should apply, given the circumstances of Thorpe’s burial. Sherry Hutt, the National Park Service’s Repatriation Act program manager, said that as long as Thorpe’s body remains in the mausoleum, it cannot be considered part of a museum collection.

Thorpe’s 1954 burial in Pennsylvania was the product of a deal between civic leaders in the downtrodden Carbon County boroughs of Mauch Chunk and East Mauch Chunk and Thorpe’s third wife, Patricia.

Spurred by local journalist Joe Boyle, the communities agreed to unite under Thorpe’s name and build a fitting tribute after Oklahoma’s governor balked at the cost.

Local leaders hoped the memorial would become a tourist attraction and inspire investment in the area, which struggled economically after the decline of the mining industry.

But in Yale, Okla., which calls itself the “Home of Jim Thorpe,” residents share the opinion that Thorpe was wrongly taken.

“We feel as though he was stolen from us, and in a way he was,” said Virginia Stanford, a curator at the Jim Thorpe Home museum in Yale.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.