For Tijuana children, drug war gore is part of their school day

- Share via

Reporting from Tijuana — The schoolchildren bounded up the rickety steps and followed the path of shattered glass into the two-story house on Laguna Salada Street. Two boys in neatly pressed gray pants flipped open their cellphones and took pictures of the pools of sticky blood. One teenager with a blue backpack pounced on a mangled bullet lying near a stained mattress.

In the living room, someone slipped on a pile of human entrails.

Downstairs, girls in blue skirts and white socks carefully avoided the blood dripping through the ceiling.

The “Scarface” poster hanging on the pockmarked wall disappeared.

The day before, a shootout between Mexican soldiers and drug cartel suspects had left three suspects and a soldier dead in the safe house at the end of a quiet cul-de-sac. Police had cleared the bodies, including the corpse of a kidnapping victim stuffed in a refrigerator. But someone had left the door open.

“Look, intestines!” yelled one teen, who was among dozens of children who streamed through the house between classes at nearby Secondary School 25.

“I think I’m going to be sick,” said one boy, covering his mouth.

“It’s shocking,” said Victor Rene, 14. “I saw four dead guys last week, but that was clean. Their heads were wrapped in tape.”

As Tijuana’s latest flare-up in the drug war rages into its fifth week, with the death toll approaching 150, violence is permeating everyday life here, causing widespread fear, altering people’s habits and exposing the city’s youngest to carnage.

Civic leaders are calling for a 9 p.m. curfew for children. Archbishop Rafael Romo has asked the media to refrain from showing gruesome photographs. One priest halts his sermons every week to demonstrate proper shootout-safety behavior: He cues a drum roll, then throws himself to the floor.

But these and other measures haven’t been able to shield children from the violence near schools, neighborhoods, busy streets and popular restaurants. Grisly public displays of death have been the hallmark of the killings since the latest violence between rival drug cartels started Sept. 26.

Bodies have been hung from overpasses. Twelve corpses, some with their tongues cut out, were tossed into a vacant lot across from an elementary school. Several men have been beheaded, and killers have left behind acid-filled barrels containing dissolved human remains.

The toll of innocent victims has also been rising. Gunmen burst into the El Negro Durazo seafood restaurant and killed two rivals and a photographer who tried to run away. A 24-year-old teacher was kidnapped outside her school. Gunmen wielding AK-47s killed two teenagers sitting outside their home after they witnessed a drug-related killing. A toddler died this week when his mother crashed her car trying to avoid a shootout between state police and suspected cartel hit men.

Tijuana has endured years of violence and waves of kidnappings that have led thousands of people to move across the border to San Diego suburbs.

Still, the recent violence is unprecedented in scale and brutality. More than 460 people have died violently so far this year, a record, according to the Baja California state attorney general’s office.

“It makes your hair stand on end,” said Father Raymundo Reyna, a popular radio show host who keeps a muertometro -- death meter -- tally. Reyna is the priest who demonstrates to parishioners how to duck when gunfire breaks out.

“We show people how to prepare for an earthquake. Now we need to train them for a shootout,” Reyna said.

Many people simply avoid public places. Families have cut back on going to restaurants. Some parents forbid their children to go to nightclubs, preferring they attend parties at the homes of people they know. More parents pick up their children from school rather than letting them take public transportation.

After eight people were killed in neighboring Rosarito Beach on Thursday, some panicked parents kept their children home, reacting to rumors that children were going to be kidnapped.

Cops, or anybody in a law enforcement uniform, are avoided; at least 10 security personnel have been gunned down in recent weeks in the Tijuana metropolitan area. Ana Luisa Angulo, a mother of four, said her daughter was recently pulled over by an officer for speeding.

“She didn’t even argue,” Angulo said. “She just wanted to get the ticket and get away from him as quickly as possible.”

For some youngsters, Tijuana’s battlefield is a playground, another childhood experience.

Down the street from Reyna’s Monte Maria Church in a tough hillside slum, kids play in another bullet-riddled former hide-out, where a family was killed this year.

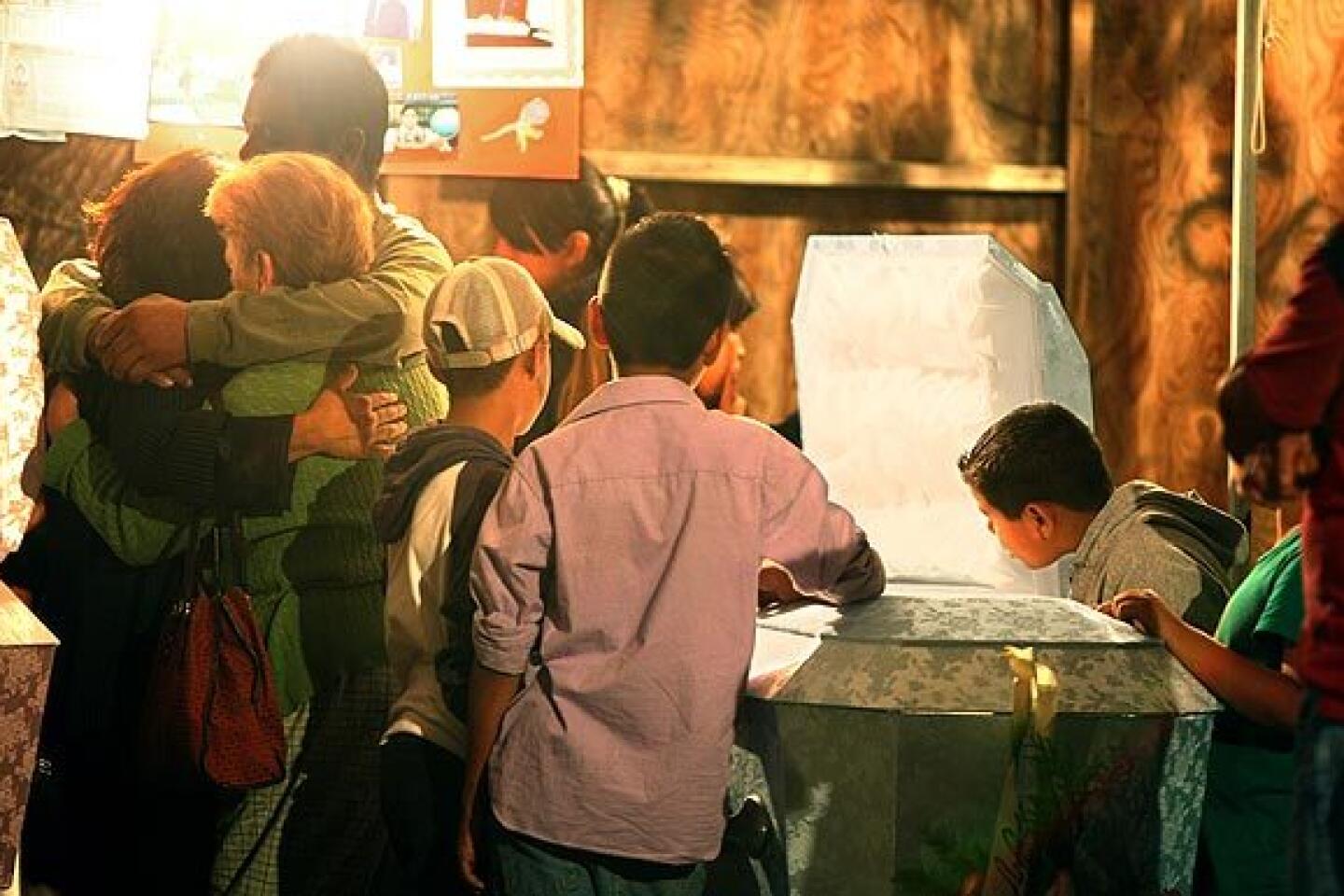

Then there are the wakes and funerals, among the few nighttime events that parents allow their children to attend.

Around the corner from the hide-out, teenagers last week stared glumly into the open caskets of Isabel Guzman Morales, 14, and Victor Corona Morales, 17, cousins who were shot to death outside their home. More than 100 people squeezed into the tiny front yard of a relative, where the caskets had been placed side by side under a tent.

Later, the teenagers climbed down staircases made of rubber tires to another wake. Inside a teetering house made of wood scraps, the kids looked into the open casket of another friend, 19-year-old Felipe Alejandro Prado, who was also fatally shot with the cousins after being chased down by unknown assailants.

While family members served coffee and cookies, relatives and friends tried to piece together the tragedies. “The killers were probably outsiders,” said Prado’s father, Martin Gomez Mejilla. “They’re taking so many innocent lives.”

Friends suggested that Prado was not an innocent bystander; he was a drug dealer who fearlessly roamed the neighborhood’s dirt streets, they said. One 11-year-old visitor seemed to want to emulate the dead teen. “When I grow up I want to be a narco, and get all the women and the money,” he said.

Such shows of bravado from youngsters, say parents and psychologists, could mask deep-rooted trauma. Many children’s anxieties are increasingly manifesting themselves in eating and sleeping disorders, they say.

“At night, some kids have nightmares,” said David Sotelo, a psychologist, “but what worries me more than the trauma is the social costs, the desensitization and the low value some kids have for human life.”

Even more troubling, say some, is a growing exhaustion bordering on indifference.

Teachers have twice had to evacuate Secondary School 25, where a razor-wire fence rings the playground. The first time, police had opened fire at the state prison a few blocks away, killing at least 20 rioting inmates. Two weeks later, a body was tossed in the street outside the school.

Last week’s shootout at the safe house forced teachers and students to hit the floor again.

When the youngsters returned for afternoon classes after visiting the house, teachers had trouble getting their attention: The students were showing off their cellphone pictures of the carnage.

A teacher asked an assistant principal to confiscate the kids’ phones and give them to their parents, so they could lecture their children. The assistant principal, Marcos Alvarez Guardado, just shrugged: “I’m sure they’ve already posted the images on the Internet,” he said. “What more can we do?”

Marosi is a Times staff writer.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.