On skid row, every storage bin tells a gritty tale

The Central City East Assn. lets the homeless keep their belongings in plastic trash bins. A few owners find jobs or homes, but many vanish without claiming their property.

- Share via

Jose Antonio Diaz dresses with Friday night bravado every day. He saunters into the skid row warehouse where his life is stored in a plastic trash bin, wearing a vivid blue Puma track jacket and close-fitting black jeans with leather shoes, his eyes hidden by shiny black and red shades.

He walks past signs in the lobby spelling out the rules: Bring ID and paperwork. Store nothing illegal, perishable or valuable. No drinking, no fighting, no defecating and no undressing. Come back every week to renew your bin.

Diaz's bin is in the back, past neat rows of hundreds of black, brown, blue and green trash bins identical to those found at the end of residential driveways. Squinting in the dimly lit warehouse, an employee finds Diaz's bin: No. 715.

There's free clothing available on skid row, but Diaz buys his own threads. He keeps them in suitcases in his bin, along with an iron, several pairs of shoes and a receipt for the dry cleaners.

Diaz moved from Bakersfield to Los Angeles a few months ago with dreams of becoming a professional pianist.

With little money and no friends in town, he ended up on skid row and his belongings ended up here, at the Central City East Assn.'s storage center on 7th Street.

He's struggling to adjust to being homeless. He often gets a bed in a shelter, but his roommates scare him. He's seen fights, mental illness and overdoses.

Fashion gives him confidence, says Diaz, 27. He takes pride in his appearance. In his bin, he keeps a giant tub of hair gel.

"I like the spiky hair, man," he says as he smears on a little reinforcement. "It's sexy."

Diaz tugs the front of his jacket and strikes a pose. "I gotta look good," he says.

Then he shrugs awkwardly, all swagger with no place to go.

The center had about 600 bins for homeless people’s belongings, and the city paid for 500 more last year. There are never enough, supervisor Peggy Washington says.

The Central City East Assn., a nonprofit group serving local businesses, opened the center in 2002 with about 300 bins for homeless people's belongings, later expanding to 600. The city paid for 500 more bins last year. There are never enough, supervisor Peggy Washington says.

The bins are free, but clients have to follow the rules, most of them written by Washington. But she spends much of her day making exceptions.

A man knocks at her office window. He has to travel to Commerce for job training at a pharmacy and won't be around to reserve his bin next week. Can he have an extension?

Washington's mouth stretches into a thin line at the word "pharmacy." She's heard a lot of excuses in her seven years here, and she's not sure working in a drugstore is the best idea for an addict. But she will bend the rules to accommodate his initiative.

"All right," she says, and gives him some extra time. "Come back Thursday."

Some of the center's clients are addicts and others face problems she doesn't understand. So she shoots down bad excuses, offers leniency for honest ones and waits. When clients reach the point where they are ready to accept help, she confronts them.

You're dying. Are you ready?"— Peggy Washington to addicts seeking help

"You're dying," she tells them bluntly. "Are you ready?"

She measures victories and defeats in two cardboard boxes along the wall of her office. One, labeled "DISCARDS 2013," holds the paperwork of those who found jobs or housing and no longer need their bins. The other, stacked to the brim, contains the rental receipts of people who never came back. It's labeled "GAVE UP 2013."

Every now and then, someone finds a job and keeps it, or gets housing and stays there. That's the best part of her job, Washington says. When someone escapes.

Abandoned items are bagged, tagged and dragged to a fenced storage area in the back. They are held for 90 days. Then they disappear into a landfill.

In the tall metal shelves that hold unclaimed belongings, hints of past lives peek through the plastic bags like puzzle pieces — romance novels, new Barbie Princess sets, strings of pearls, blocky old computers and a cardboard advent calendar, the chocolate crumbling inside.

Diaz keeps a painting of the Virgin of Guadalupe in the mesh pocket of a suitcase in his bin.

His best friend made it for him during high school in Mexico City. The painting hung in his bedroom in Mexico, and it traveled with him to his uncles' home in Bakersfield, when Diaz left his homeland at the age of 18.

His uncles treated him like a son, and begged him not to leave. He had no family in Los Angeles, no money saved. But Diaz left anyway. He couldn't stay in Bakersfield, a city too small for his dreams.

In the bottom of his bin, Diaz keeps a book of Spanish poetry, a battered cream-white volume with gold leaf pages. He cradles the book by the spine, and it falls open to a page that's been folded over.

The poem is "A Unos Ojos Astrales," by Jose Polonio Hernandez. He starts to read, and his voice, halting in English, moves confidently in Spanish.

If God, one day

blinded all sources of light

The universe would be lit

by those eyes that you have.

He sighs and remembers the girl he left in Bakersfield. They dated for four years, and she too begged him not to leave, but he left anyway.

"We were together, but no more," Diaz says. He closes the book, places it in the bin and goes silent.

He wakes by 6 a.m. and the day is full of hours to question his decision. Why come to Los Angeles, where he can barely find his way around? Should he leave again?

So far he's shoved his doubts aside.

His true calling, he says, is to be a musician. Diaz keeps a large collection of CDs in his bin. He plays piano, loves Mozart and Coldplay, but he has no place to practice.

His voice is low and urgent, as if he's afraid of being overheard. "I want to make my dream in Los Angeles," Diaz says. "I want to be a good musician, but I need practice. I need to go to school."

He lifts a green laundry bag. He smiles, showing white teeth.

"Someday," he says, "something beautiful is coming."

"Lots of people have lots of interesting stories," Peggy Washington says. "What I always ask is, what's next? What are you going to do about it?"

Washington has seen many clients like Diaz — aspiring actors, hopeful artists and businessmen who just need a bit of startup capital.

"Lots of people have lots of interesting stories," she says. "What I always ask is, what's next? What are you going to do about it?"

Fernando, who is in his mid-40s and like some of the others at the center only wanted to give his first name, keeps a chessboard in his trash bin — printed black and white squares on a piece of paper backed with tape and corrugated cardboard.

He used to be a pretty good player, but then he lost his job and apartment last year. It's hard to find a good match on skid row. He hasn't played in months.

Fernando was laid off from his job as a Spanish medical translator in February 2012. His application for unemployment benefits was denied because he hadn't worked long enough.

Becoming homeless stunned him, he says — "like someone puts explosives in your house and blows everything up."

Fernando blames his situation on the economy. The only jobs he can find are backbreaking warehouse jobs, or positions outside the county that require long, expensive commutes.

"If someone was to make it easier on me, then yeah I would go," Fernando said. "They tell me, you have to be open to everything, but what is everything?"

Washington, 55, understands Fernando's pessimism better than most. She spent the better part of her 40s on skid row, addicted to crack cocaine.

When a client complains that she doesn't understand his troubles, she fires back quickly: "Gladys and 7th was my home. Where's yours?"

I used to have stuff like that. I was going to use it one day. Then one day it didn't matter any more."— Oscar, a homeless man with no mementos

But she's made all of the same excuses. They sound especially hollow to her now, after seven years of being sober.

"Skid row is too easy," Washington says, ticking off why.

The government sends you a check every month — $221 for general relief, more for disability. A police officer wakes you in the morning. Municipal employees keep your section of the sidewalk clean. Homeless service providers give you food, clothing and medical care. And the Central City East Assn. gives you a place to keep your belongings.

Washington compares it to living in a hotel where everything is free. Many of the center's clients become complacent, she said.

Oscar, a man in his late 50s, keeps pink pills, yellow pills and big red pills in a blue felt bag decorated with white snowflakes

Oscar says he needs the medication for high blood pressure. He also keeps a pill bottle full of green liquid that he says is alcohol. It also serves a need, and that's all he wants to say about it.

He came to Los Angeles from Texas to work at the docks. He's been living on skid row for about 15 years, and he has six words for the story of how he got there.

"No money, no job, no place," he says.

Oscar also keeps several changes of clothes, some bottles of water and food in his bin — supplies for what he calls his "immediate need." There's also a spray bottle of Pine-Sol, deodorant and soap. The bin isn't a place for memories or valuables, Oscar says.

Several times a week, the staff must throw away meager possessions abandoned at the warehouse.

"I used to have stuff like that," he says. "I was going to use it one day. Then one day it didn't matter any more."

Oscar keeps two mirrors taped to the inside of his trash bin lid. When the bin is open and the lid is upright, he uses the mirrors to watch his back as he sifts through his possessions.

On a recent weekday, Washington crouches amid a graveyard of plastic bags and suitcases at the back of the warehouse. Several times a week, she and the staff must throw away abandoned possessions.

Today, she is reminded of Juan Figueroa, a client of the center who was an alcoholic, Washington says, and a lot of fun.

"He used to come in, maybe drunk, and play guitar and sing for everyone," she says.

Figueroa died in January. The Los Angeles County coroner's office lists his case as a natural death caused by prolonged alcoholism, but Washington has another name for it.

"The streets took him," she says.

After Figueroa's death, his possessions were bagged, tagged and taken to the back with the rest. All that remains of him is a bag of clothes and some plastic water bottles.

His 90 days are ending soon.

More great reads

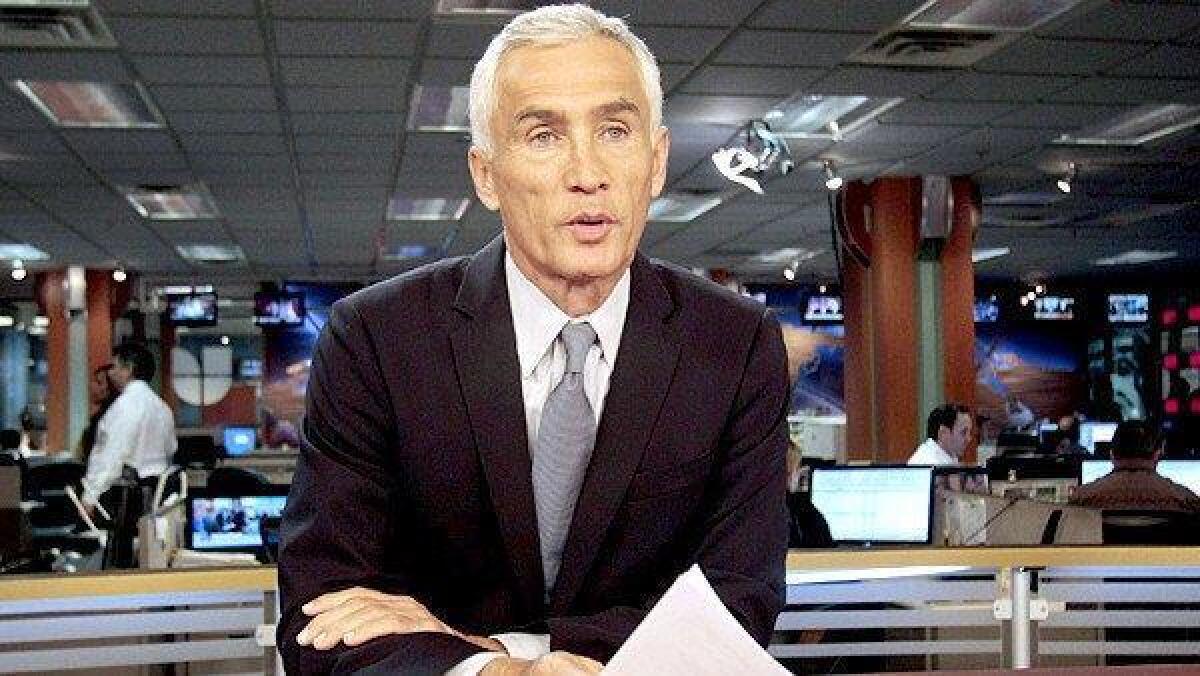

Univision's Jorge Ramos a powerful voice on immigration

Jorge Ramos works in the studio in Miami, Florida.

Once you are an immigrant, you never forget that you are one."

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.