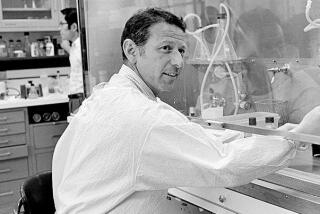

Samuel M. Genensky dies at 81; mathematician invented tools for the near-blind

Samuel M. Genensky, a former Rand Corp. mathematician and inventor whose near-blindness led him to help others cope with limited eyesight and become more self-sufficient, died June 26 at his Santa Monica home. He was 81.

The cause was complications of heart disease, said LaDonna Ringering, president and chief executive of the Center for the Partially Sighted, a West Los Angeles facility that Genensky founded in 1978.

Genensky was best known for developing a kind of closed-circuit television that became the prototype for the video magnifiers sold around the world today that enable people with severe visual impairments to read books, magazines and other conventionally printed materials.

“Sam is universally known as a pioneer of assisted technology for people with partial vision,” said Tony R. Candela, a deputy director in the California Department of Rehabilitation who oversees services for the blind and deaf. Genensky’s magnification machine “ended up revolutionizing the ability of people with partial vision to read printed material,” Candela said.

The positive reaction to the invention persuaded Genensky to become an advocate for the partially sighted, who number about 14 million in the United States.

“When the partially blind went out in the world, they found that they either got no services at all or services that were appropriate for people who were totally blind,” Genensky told an interviewer this year. “Neither of these alternatives made much sense to me.”

Genensky, who was born in New Bedford, Mass., on July 26, 1927, was determined not to be treated as a blind person, even though he met the legal definition. His eyes were burned shortly after birth when a delivery-room nurse accidentally administered the wrong eyedrops to guard against infection. No sight remained in his left eye and he had only 20/1000 vision in his right eye.

Hardworking and exceptionally bright, he completed the first eight years of school in seven years. After elementary school, he was sent to the Perkins Institute for the Blind in Watertown, Mass., where he refused to use Braille even though he knew it. He preferred to use what little sight he had, even if it meant holding a book up to his nose.

Frustrated by teachers’ demands that he “act like a well-behaved blind child,” he left Perkins for a regular public high school in New Bedford. To keep up with his normal-sighted peers, he took his father’s World War I-era binoculars to geometry class one day and was delighted to discover that he could see what the teacher was drawing on the board.

With the help of a doctor, he added another lens to one side of the binoculars, essentially creating a bifocal system that allowed him to read the blackboard in the distance as well as the book on his desk. He began to earn A’s.

This contraption, though cumbersome, worked well enough to get Genensky through high school, as well as four years at Brown University, where he graduated magna cum laude with a bachelor’s degree in physics in 1949. He earned a master’s in pure mathematics from Harvard in 1951 and a doctorate in applied mathematics from Brown in 1958.

In the late 1950s, not long after joining Rand, a colleague, Paul Baran, noticed how Genensky had to work slumped over his drawing board with his nose to the paper. Baran suggested that there had to be a way to improve the mathematician’s ability to see.

With Baran and other scientist and engineer friends, Genensky hooked up a closed-circuit TV with a camera. It not only magnified the type on a page but had controls for brightness and contrast. Genensky didn’t have to slump over his desk anymore.

When the device was publicized as “Sam Genensky’s Marvelous Seeing Machine” in a 1971 issue of Reader’s Digest, the Rand mathematician was flooded with thousands of requests a week from partially sighted people who wanted to try it. Many of them said the magnifying machine enabled them to read printed matter for the first time. “I couldn’t turn my back on them,” he said in 1994, recalling his decision to devote himself to working for the partially blind.

Another innovation from Genensky’s two decades at Rand sprang from his experiences looking for the bathroom. The signs marking Rand’s restrooms were too small for him to read unless he put his face right up to the door. All too often he was peering at the wrong door when it opened and a startled woman came out.

When a Rand guard asked why he was smelling restroom doors, Genensky knew he had to find a solution to the dilemma.

“He’s the guy responsible for the triangle and circle,” Baran said, referring to the widely adopted system of a triangle-shaped sign to identify the men’s room and a circle-shaped one for the women’s room. Genensky’s brainstorm eventually became the standard for marking public restrooms in California, years before similar federal requirements were introduced in the 1990s.

In 1993, when fragments of scar tissue began to cloud his “good” right eye, Genensky underwent a cornea transplant, as well as cataract removal and pupil reshaping. When the bandages were removed, a new world opened, especially in his perception of color. For instance, he saw that his wife was a redhead, not a brunet as he had thought.

The visual improvements lasted for more than a decade, until other age-related health issues rendered him completely blind.

Genensky is survived by his second wife, Nancy Cronig; daughters Marsha and Judy; stepchildren Andrea Cronig Mindell, Mitchell Cronig and Adam Cronig; and four grandchildren. Memorial donations may be sent to the Center for the Partially Sighted, 12301 Wilshire Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90025.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.