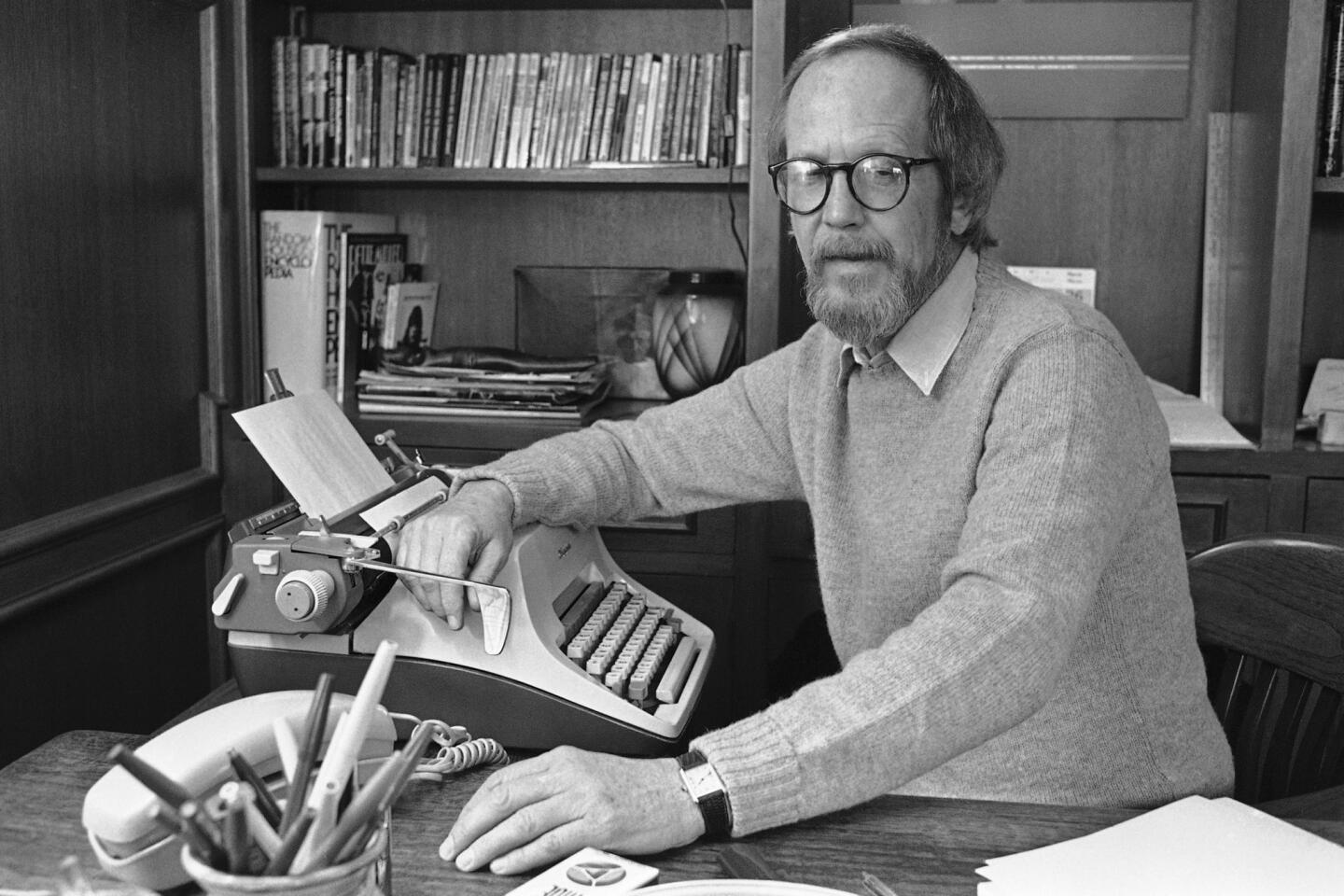

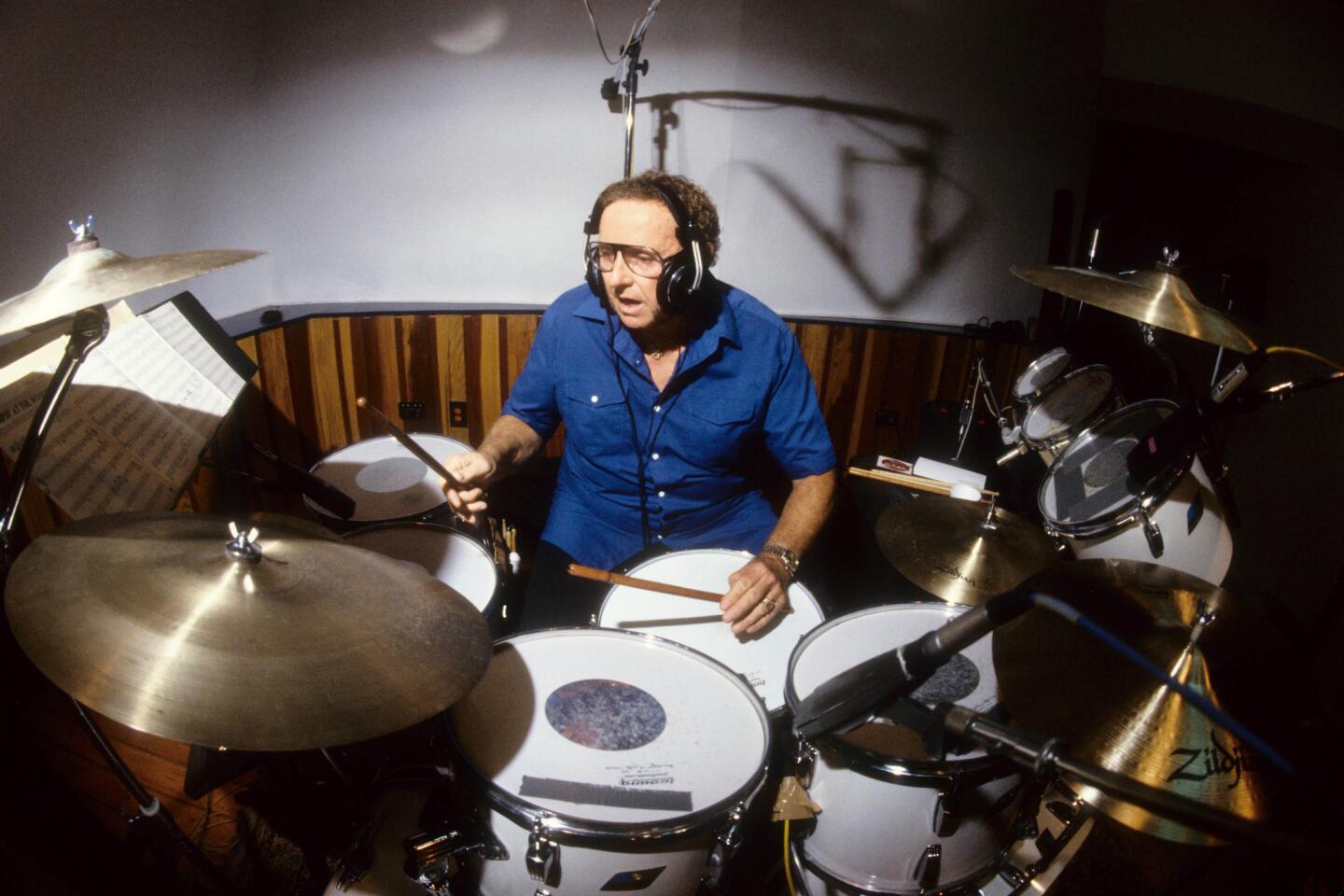

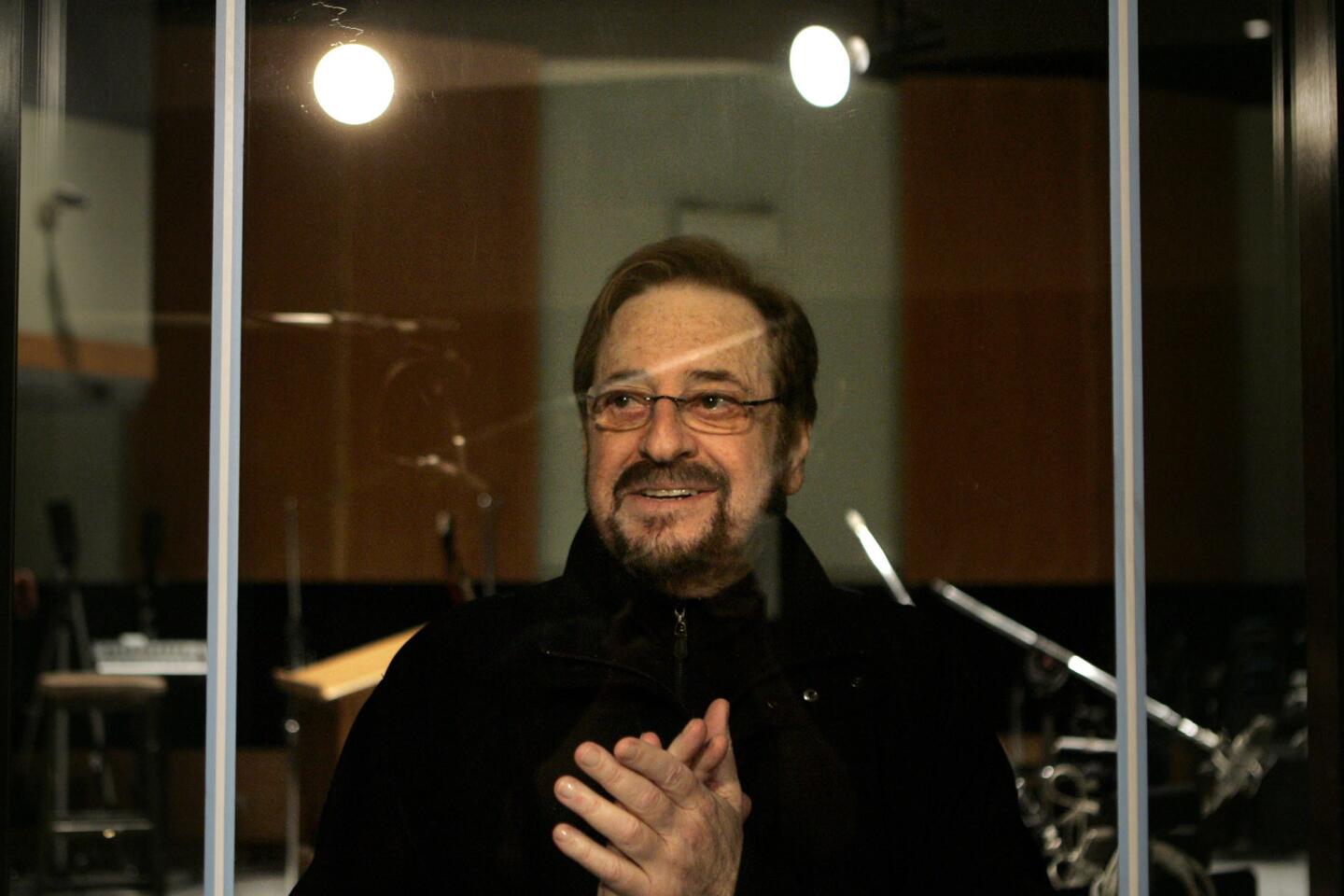

Murray Gershenz dies at 91; music store maestro, TV grandfather

Murray Gershenz bought his first record when he was 16 and never stopped.

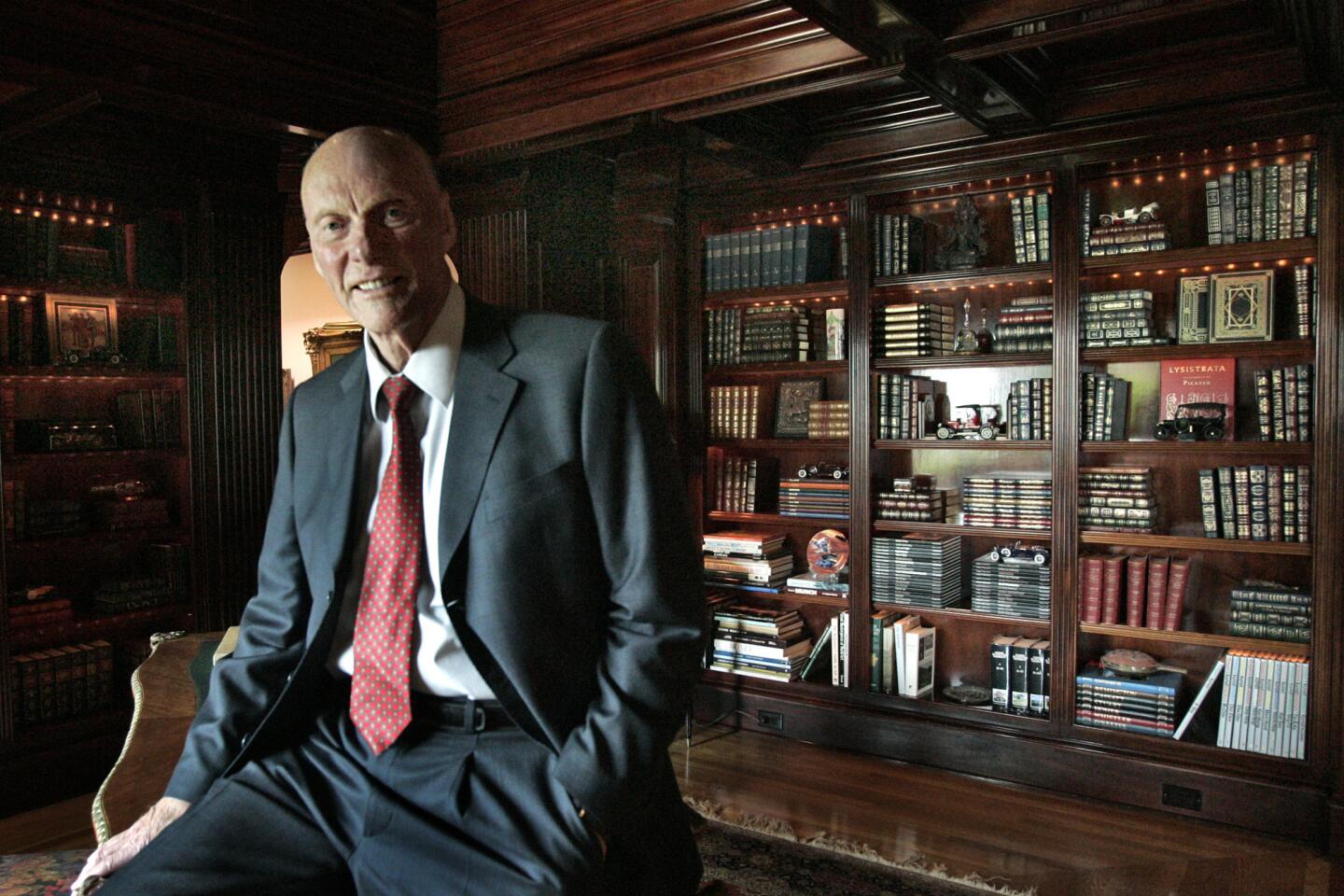

Over the decades, he acquired more than 400,000 and sold them from a Los Angeles store called Music Man Murray. Two floors were crammed to the rafters with cantatas, sonatas, hulas, horas, polkas, rock, blues, bop, even circus albums. Records jammed three warehouses and every room in Gershenz’s apartment. If stacked, Music Man Murray’s tower of wax would have soared well higher than the Empire State Building.

When advancing age and increasing rent caught up with him, Gershenz did what came naturally for a former synagogue cantor who used to lunch with Milton Berle: He went into show business. Starting with a bit part – Uncle Funny -- in “Will & Grace” when he was 79, Gershenz appeared in films such as “The Hangover” and “I Love You, Man,” as well as TV shows like “Parks and Rec” and “Mad Men.”

PHOTOS: Notable deaths of 2013

Auditioning several times a week even as he was minding the store, he was passionate about both his old records and his new career.

“I try to take care of this place,” he said in 2011 as he surveyed his sagging store shelves, “but in my head is: `What’s my next gig?’”

Gershenz died Wednesday of an apparent heart attack, family members said. He was 91.

“He was cut down in his prime,” said his son Irv Gershenz.

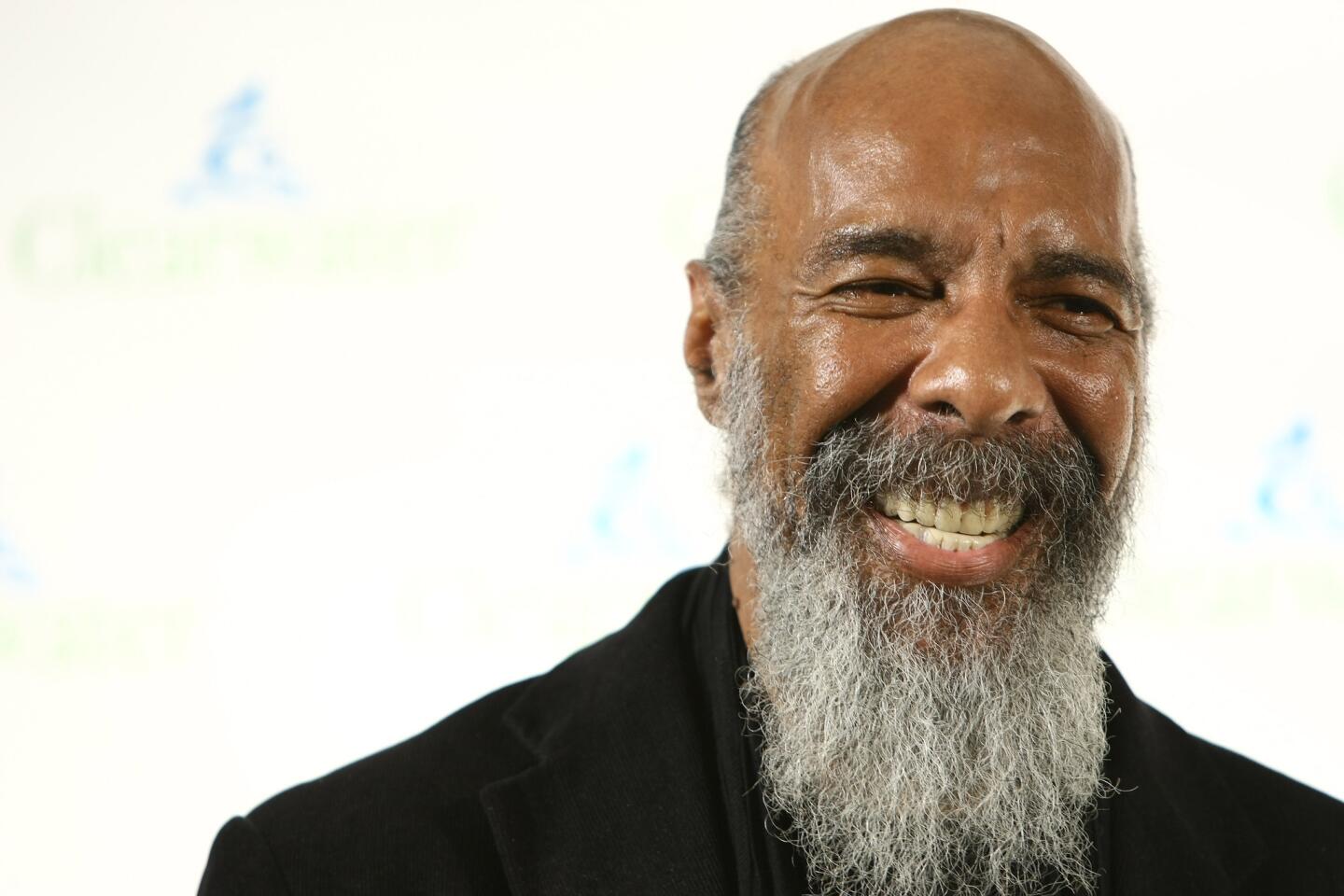

On screen, Gershenz played a role that seemed to naturally suit him: The instantly lovable old man.

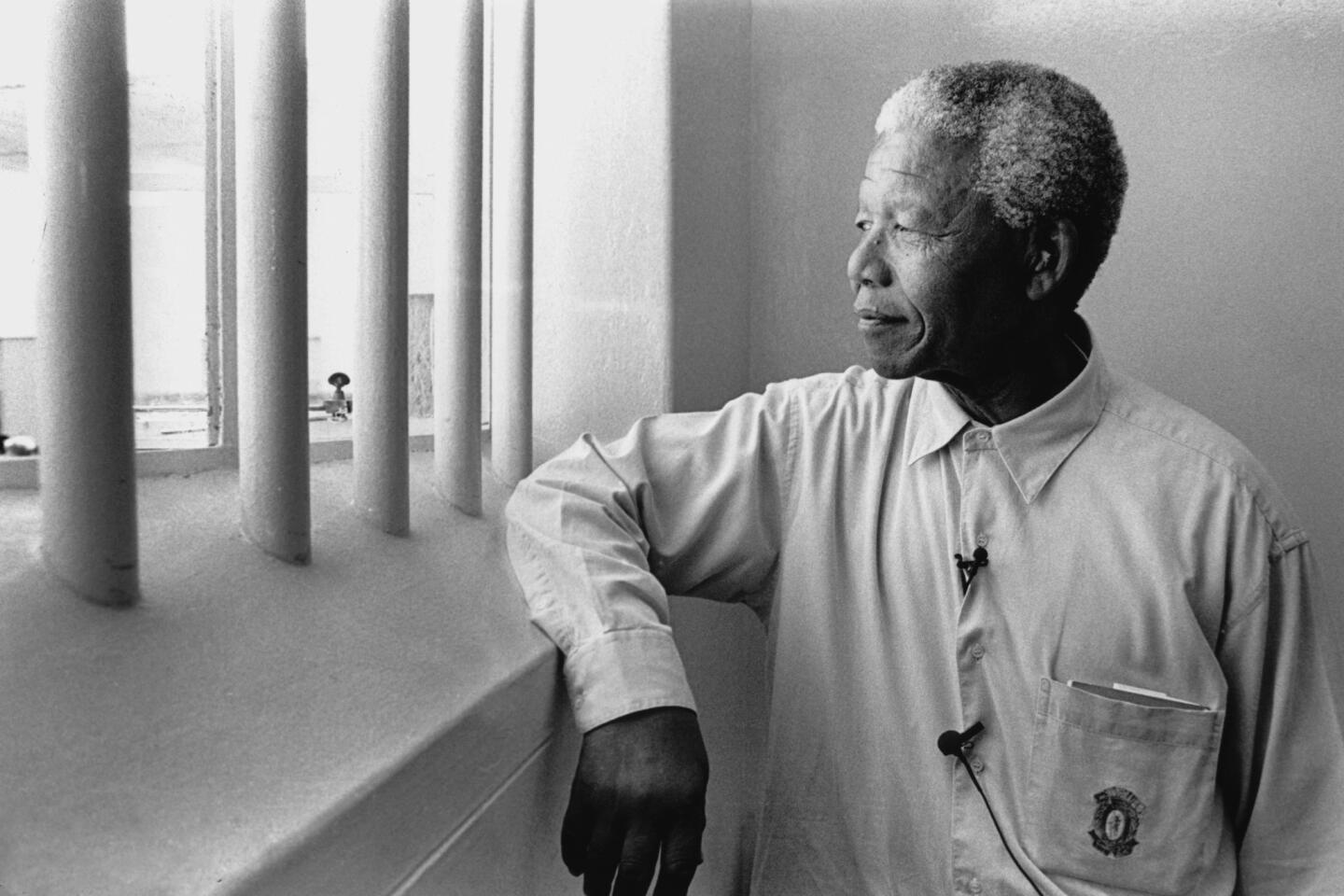

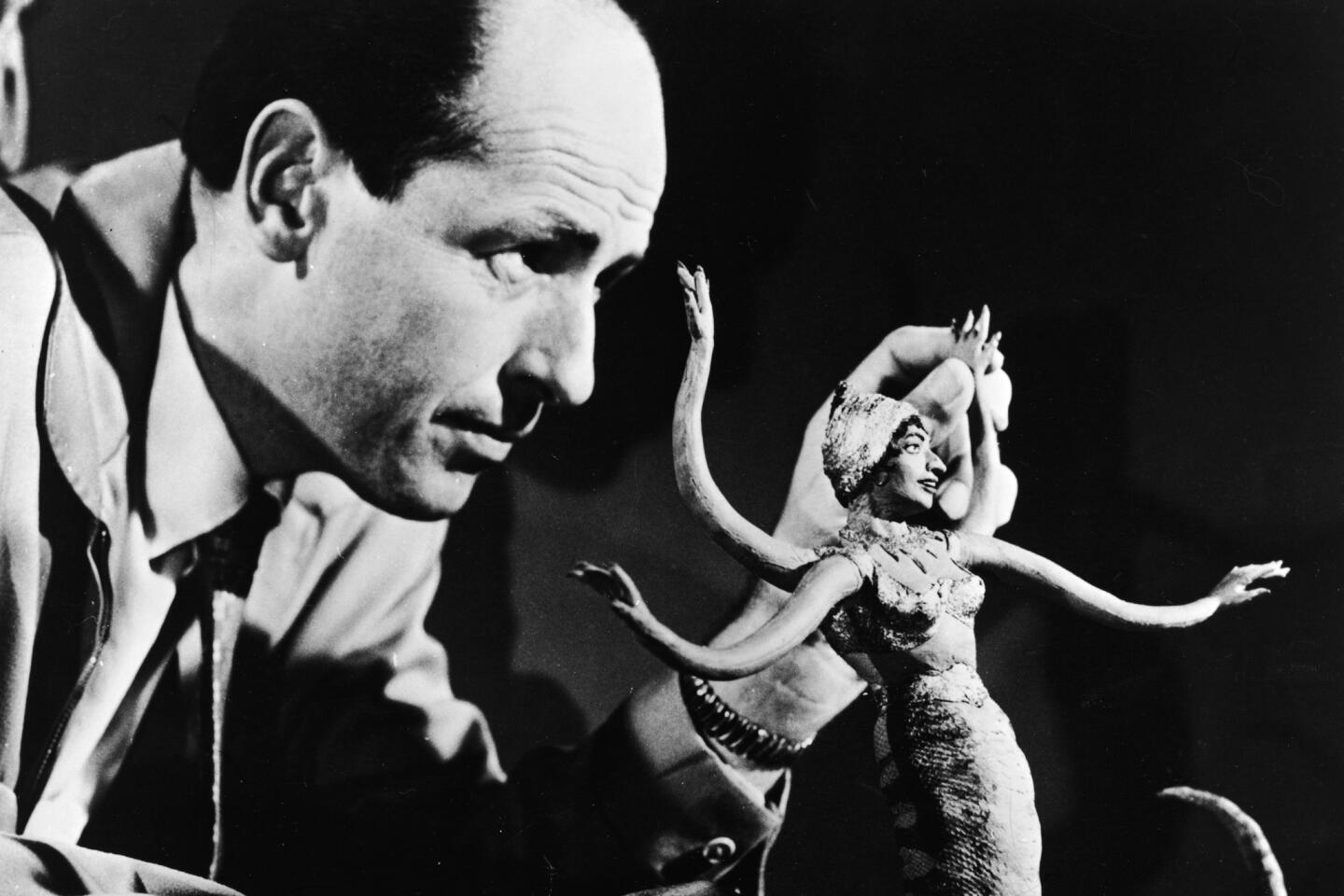

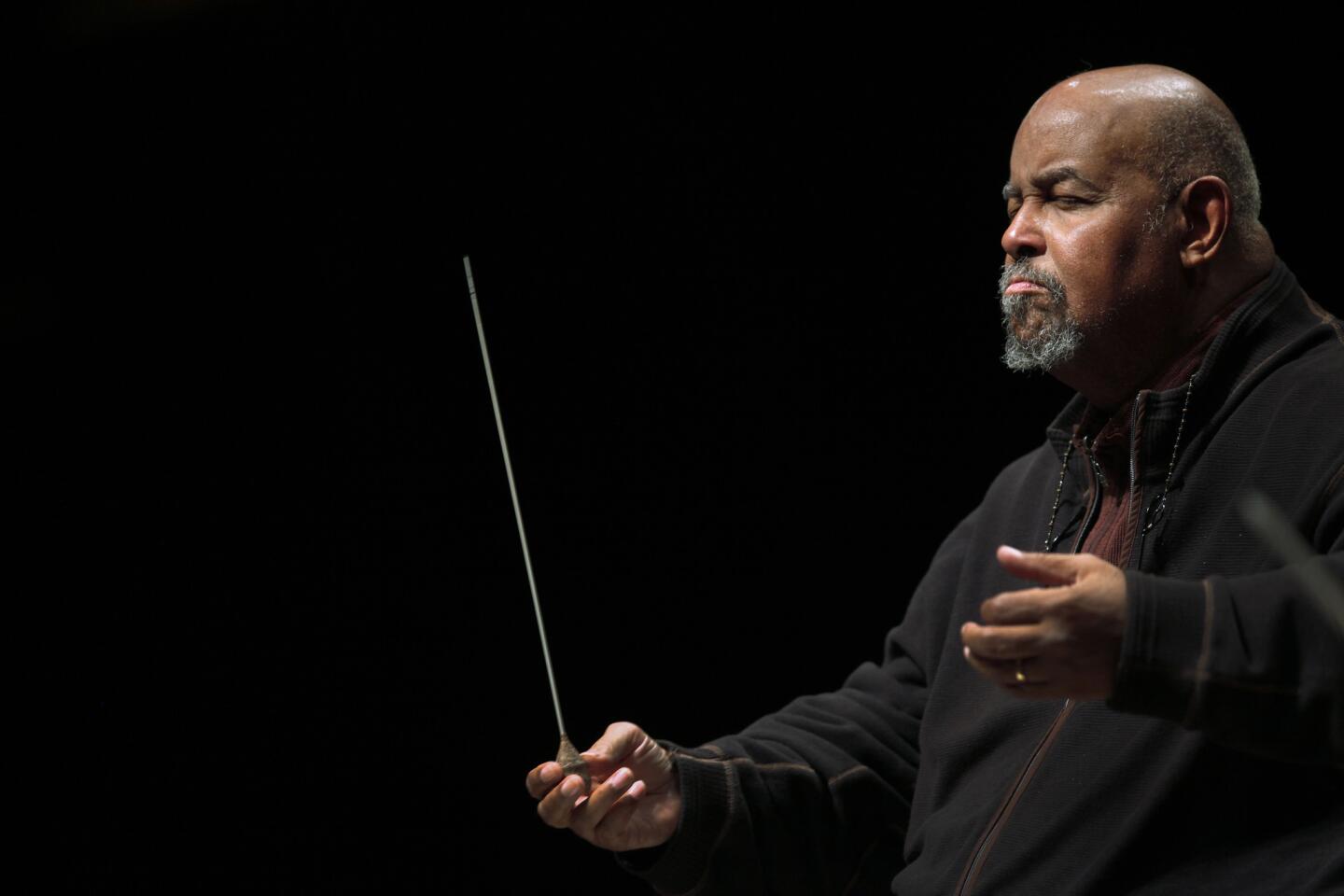

He had “the worn and gentle face of a veteran comic,” Los Angeles magazine said in 2007, “an expressive forehead unencumbered by a hairline, twitchy lips that he puckers into punctuation marks, and eyes that work hard to make punch lines funnier than they are.”

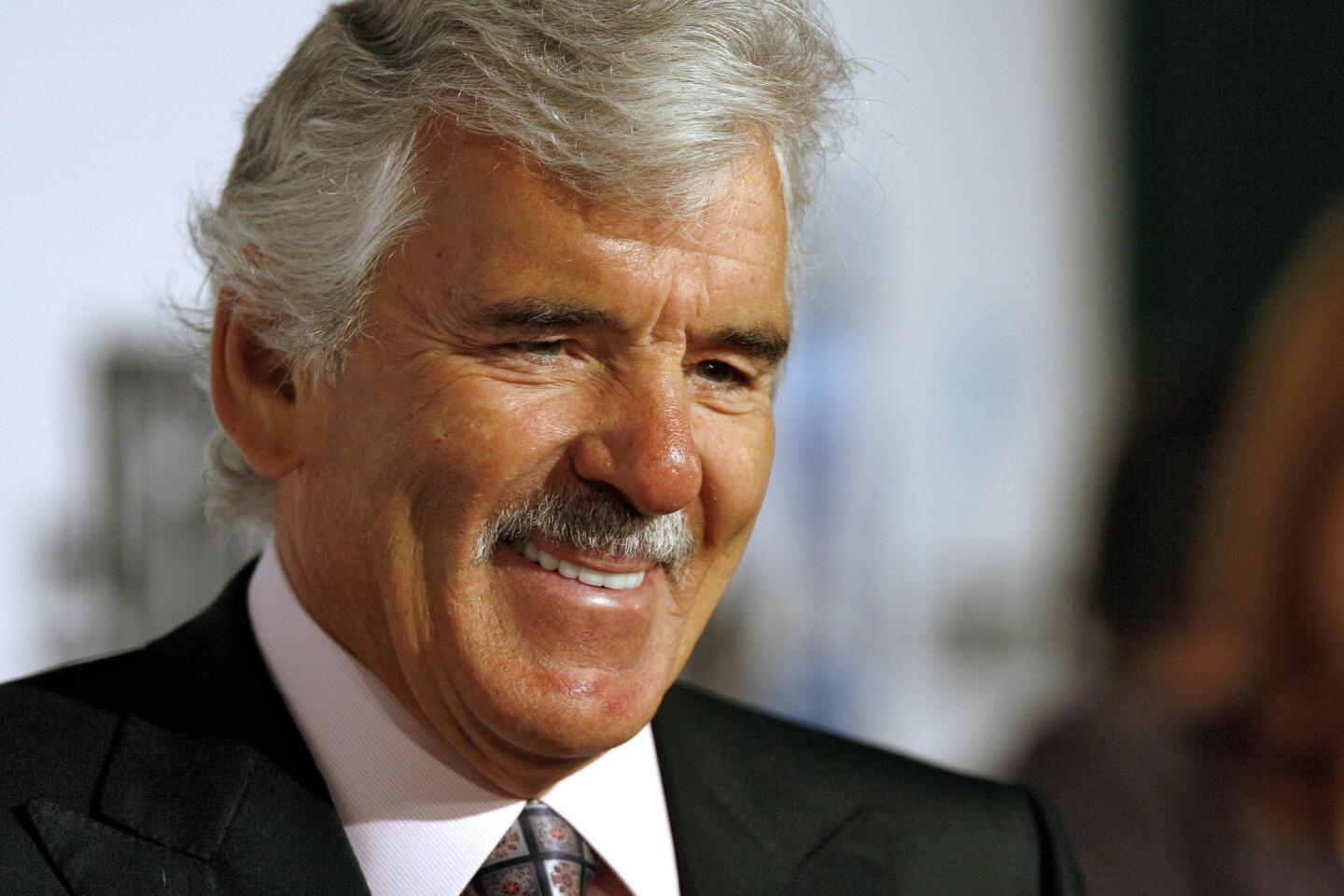

It was a look that worked well in comic pieces with Jay Leno, Jimmy Kimmel and Sarah Silverman.

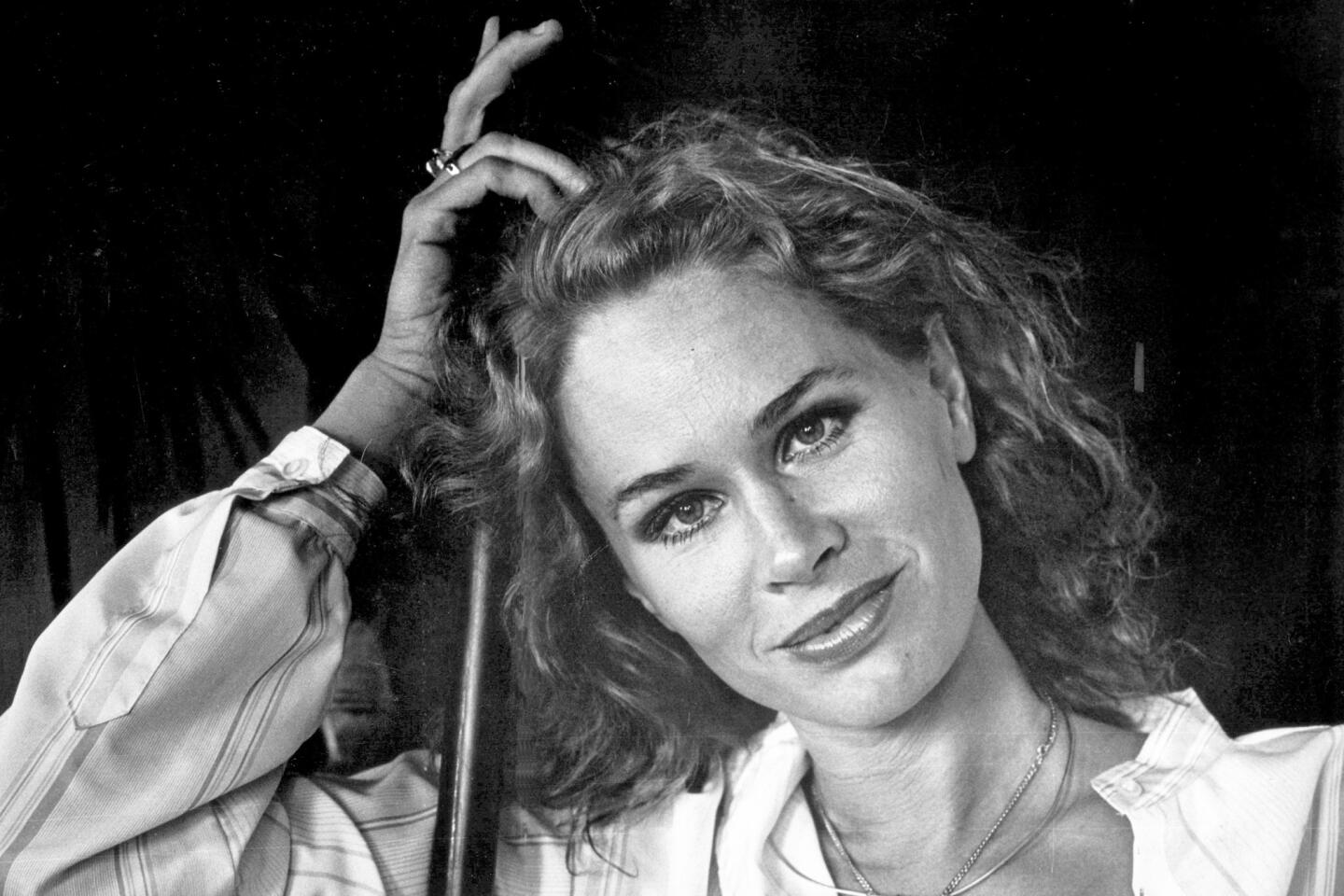

“He quickly became the go-to actor for elderly characters because he was so natural and effortless,” Silverman said Friday. Featuring him on six episodes of “The Sarah Silverman Program”, she gave him a lot to be natural about, including, in “Wowschwitz,” a comedic turn as a closeted, former Auschwitz guard hijacking a Holocaust observance on orders from a commandant played by Ed Asner.

Taking an improv class for the fun of it in the late 1990s, Gershenz was spotted by Corey Allen Kotler, an actor who became his manager.

“There was just a magic inside him,” Kotler said. “He was Everyman’s beloved grandfather.”

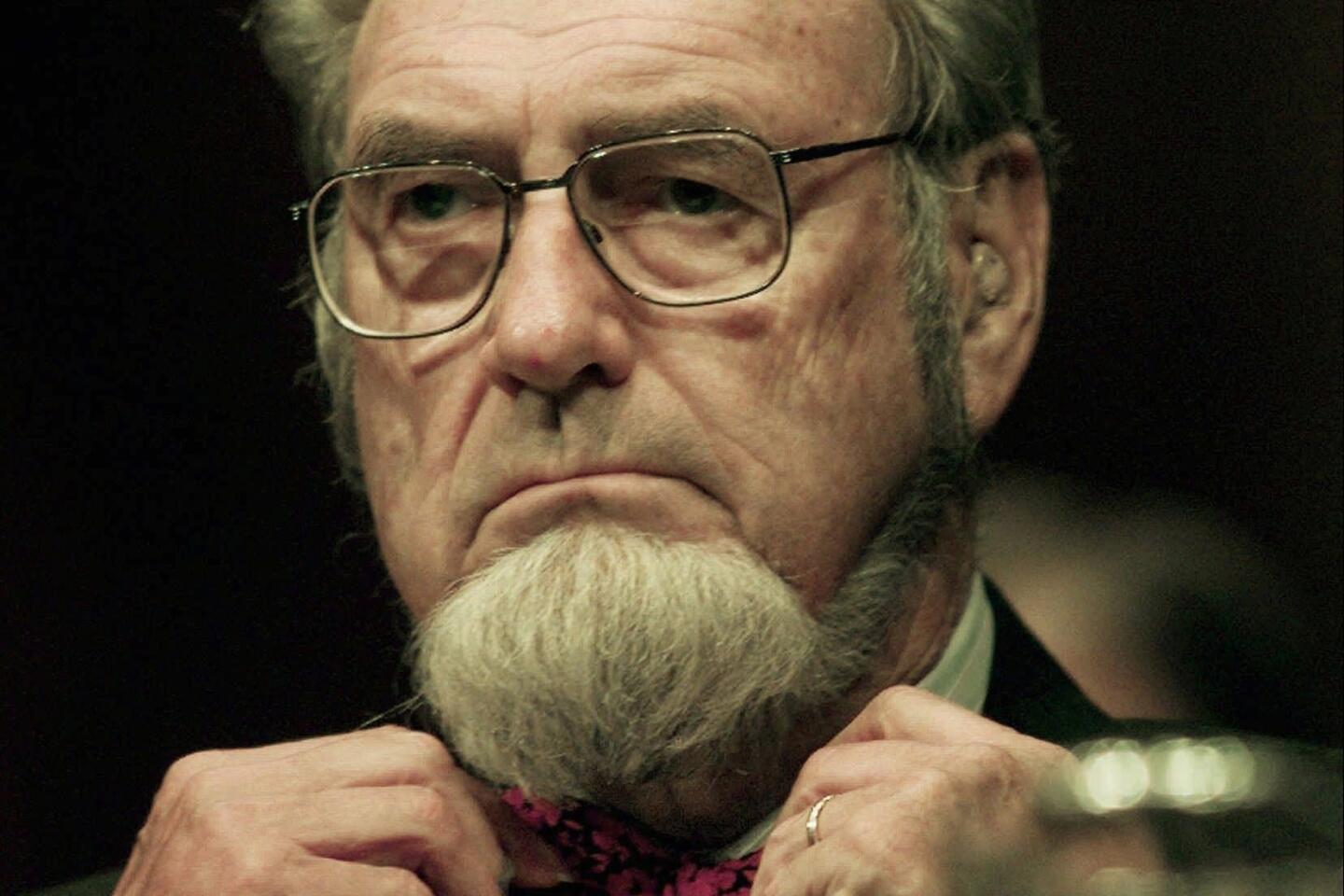

Born May 12, 1922, in New York City, Gershenz was the son of a cabdriver whose fares included Babe Ruth. Fascinated by opera at an early age, he performed as Poobah in “The Mikado” at the 1939 New York World’s Fair and later appeared with the St. Louis Opera.

Working as a waiter in New York nightclubs of the 1940s only broadened his appreciation of music. He had never heard of Billie Holiday until he served tumbler after tumbler of brandy to her when she played the Downbeat.

“I was knocked out,” he later recalled. “Here was this woman telling stories with this unbelievable voice. It changed the way I thought about music.”

Drawn to Los Angeles by friends in 1950, Gershenz picked up work as a cantor, singing at services in Santa Monica and the San Fernando Valley. Not a religious man, he left what he later called “the cantor industry” in search of an enterprise.

An inventor, he thought his artificial flagstone might find a home in the city’s burgeoning suburbs. It wasn’t in the cards, but he did marry a fellow inventor, Bobette Cohen, and the two turned his overflowing record collection into a business that would last more than a half-century.

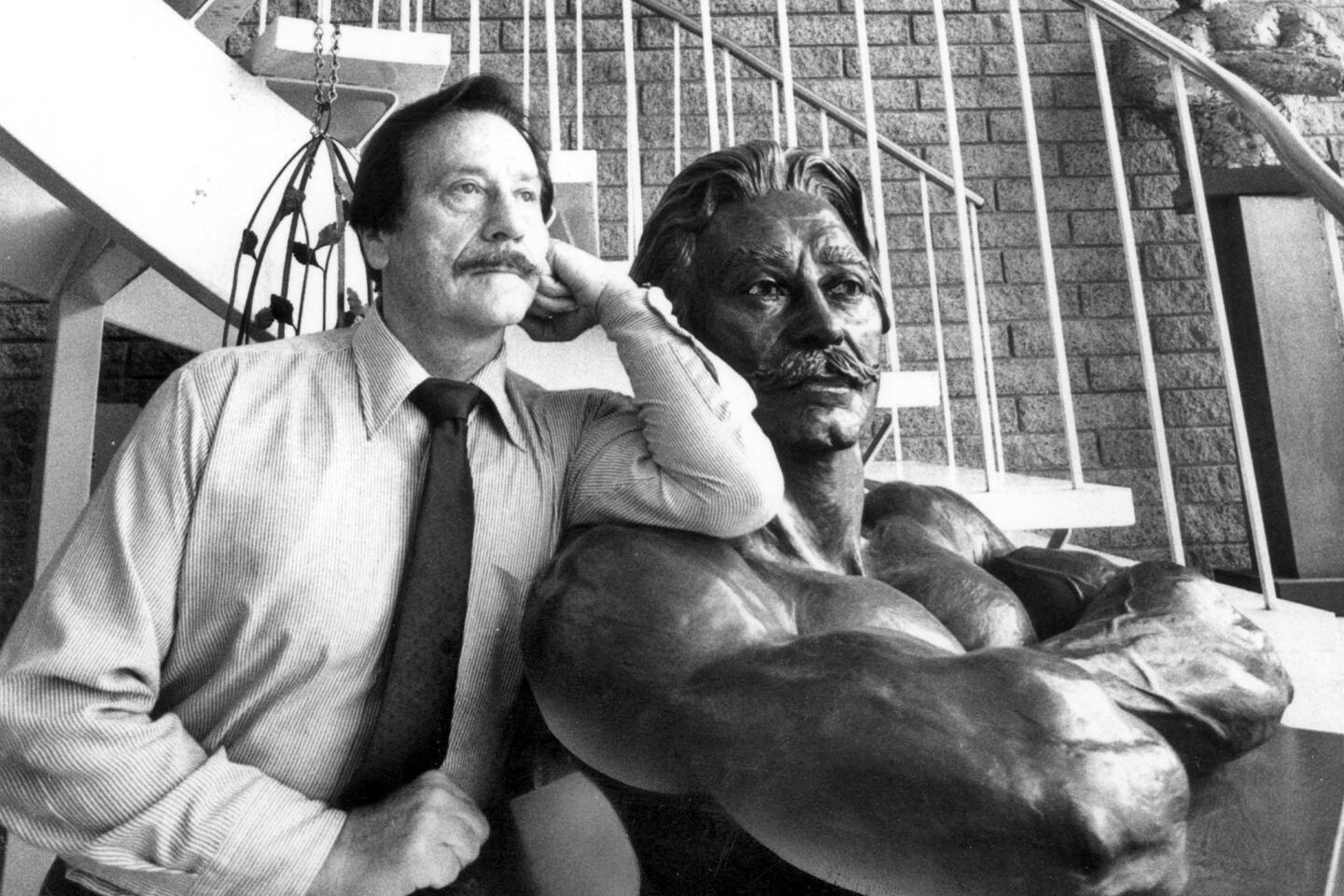

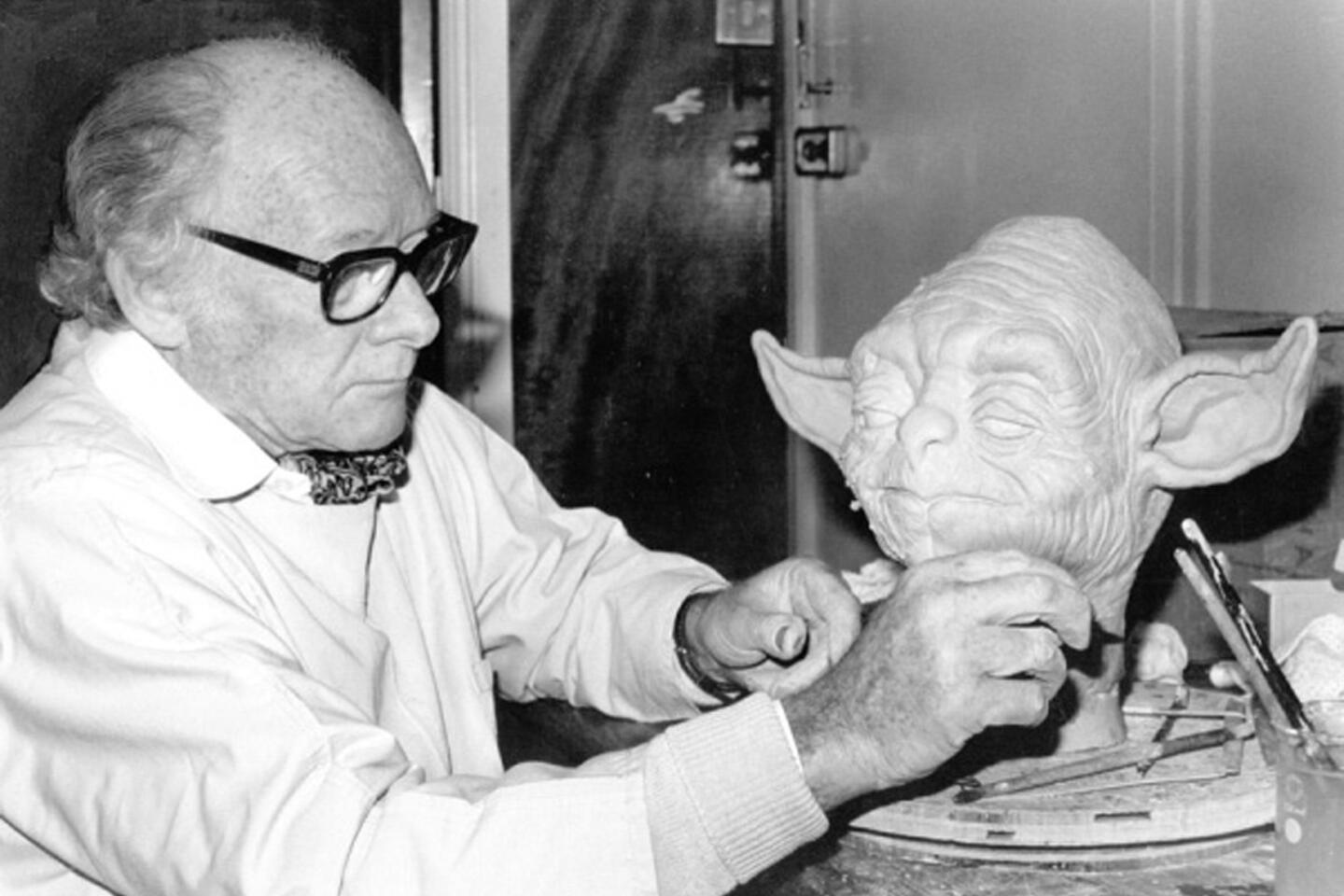

Opened in 1962, Music Man Murray was located first in Hollywood and, from 1986 until it closed last June, on Exposition Boulevard in L.A.’s West Adams neighborhood. In addition to its trove of records and crates of century-old Edison cylinder recordings, Music Man Murray also sold Victrolas, phonographs and vintage hi-fi systems.

The store attracted entertainers like Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington and B.B. King looking for their own earlier work, as well as ordinary lovers of hard-to-find music, such as Richard Parks, who made a documentary about Gershenz and his records.

“I started collecting old hillbilly music in high school and Music Man Murray was on the list of places you had to go to find that kind of stuff,” said Parks, whose “Music Man Murray” came out in 2012. “He was the godfather of the used-record store.”

As LPs gave way to CDs in the 1980s, customers dropped by with requests that chain music stores couldn’t fulfill.

“I get calls like, ‘My Uncle Charlie passed away and this was his favorite song and it goes like this, and we want to play it at his funeral,’” Gershenz told an interviewer.

In 1999, Milton Berle bet a friend that Gershenz couldn’t locate a 78 called “Cohen on the Telephone”, a dialect sketch first recorded in 1913 by comedian Joe Hayman. Uncle Miltie lost, Gershenz gleefully told a Times reporter just before he was to deliver the pristine disc over lunch.

“If I can’t find it, forget about it,” he said.

In his later years, Gershenz’s joyful obsession was bleeding cash. Placing his vast collection on the market in 2010, he found no takers.

Last June, Gershenz finally struck a deal with a buyer in Brazil, whom he never publicly named. Five 52-foot-long tractor trailers carted off the sound archive that started with a 16-year-old boy buying a recording of arias by Swedish tenor Jussi Bjorling.

The record had long since shattered but Gershenz kept the label.

In addition to his son Irv, Gershenz is survived by son Norm; daughter Nada Pedraza; two grandchildren; two great-grandchildren; and an aunt and uncle in Florida. His wife Bobette died in 1999.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.