Architect Dion Neutra, who fought to save his father’s iconic buildings, dies

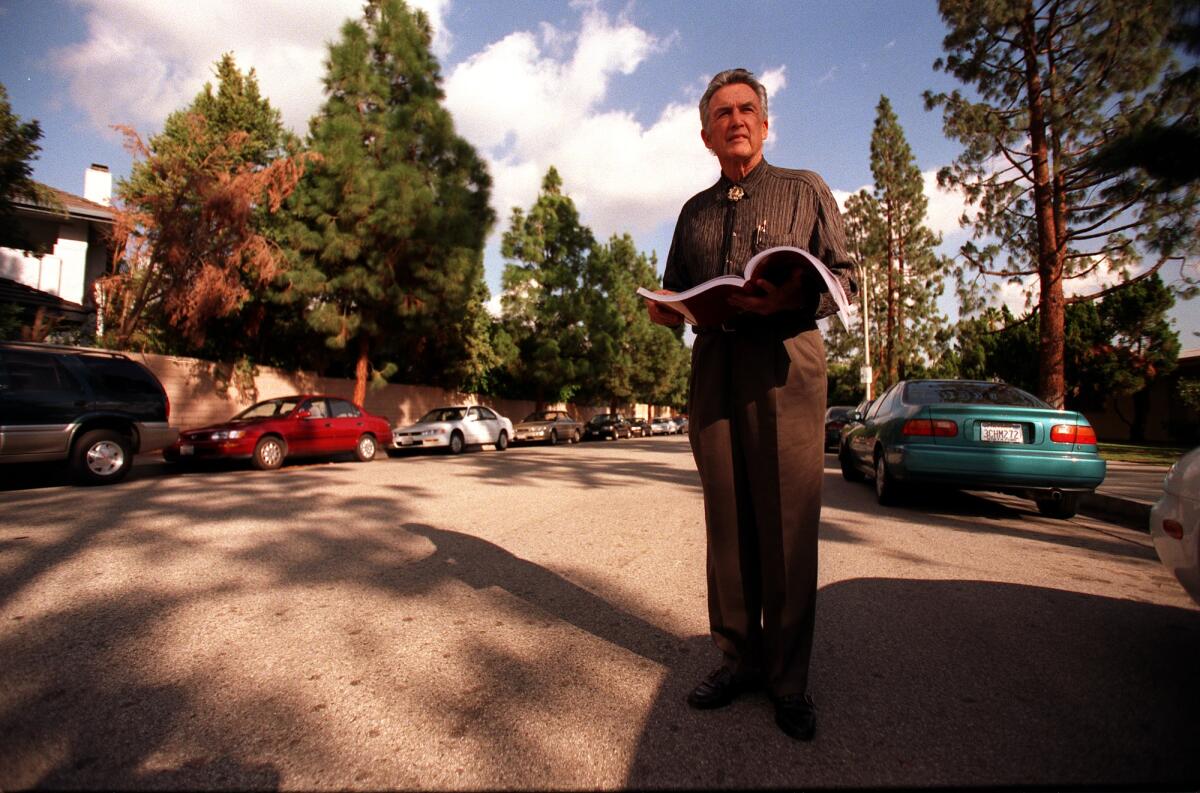

Dion Neutra, the son of the 20th century architect Richard Neutra and a practitioner in his own right who also waged a decades-long war to save his father’s iconic buildings from the ravages of time, remodeling and demolition, has died at his home on Neutra Place in Silver Lake, a neighborhood studded with Neutra architecture.

Neutra, who was 93, died Sunday in his sleep, said his brother, Raymond Neutra.

As the scion of an architecture practice synonymous with International Style modernism, Neutra was a link to the generation of 20th century architectural titans that included his father, Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier, Marcel Breuer, Walter Gropius, Eero Saarinen, Alvar Aalto, Louis Kahn and Rudolph Schindler.

Richard Neutra, a Viennese émigré who came to the United States in 1923 to work with Frank Lloyd Wright, arrived in Los Angeles in 1925, the year before his son was born, and began building.

The father and son, individually and in collaboration, executed hundreds of houses and civic projects. Many of them received laurels from the American Institute of Architects, were designated as landmarks, and made alluring motion-picture cameos — as Richard Neutra’s 1929 Lovell Health House (the first steel-frame dwelling in the United States) did in the 1997 movie “Hollywood Confidential.”

Between them, Richard and Dion Neutra exerted their influence upon the built environment and visual aesthetics of Los Angeles for nearly a century.

The lithe and airy structures were executed in a palette of no-nonsense glass, steel, concrete and wood — gleaming and seemingly machine-made. At once elegant and breezy, and articulating Southern Californians’ desire for an indoor-outdoor lifestyle, Neutra architecture achieved global renown as a symbol of Los Angeles, much like the music of Brian Wilson, the art of Ed Ruscha, and the novels of Raymond Chandler.

Dion Neutra continued the practice after his father’s death, in 1970, completing buildings of his own, such as the Huntington Beach Central Library and Cultural Center, declared “magnificent” by the Los Angeles Times when it opened in 1975. With its soothing, earth-toned interiors, copious plantings and water features, the facility has the feeling of a futuristic pavilion sprouting from a botanical garden. It remains a vibrant focal point of the community and, despite some alterations over time, is arguably the younger Neutra’s most significant project.

But the architect was perhaps best known for his work as an aggressive and sometimes prickly steward of the Neutra legacy. He campaigned vigorously for the preservation of modernist buildings, including his father’s Cyclorama Center at the Gettysburg National Military Park, a 1962 visitor facility that the National Park Service earmarked for demolition in the 1990s.

That battle dragged on for more than a decade and generated national headlines as architectural historians, architects, and fans of modernism fought Civil War historians, reenactors, and the National Park Service to a standstill. Neutra helped collect thousands of letters in defense of the structure, including one from Frank Gehry, who wrote that Neutra’s building “reflects the highest ideals of his own time, and deserves the highest appreciation of ours.” The stalemate was finally broken in 2013, when the Cyclorama Center — once deemed eligible for the National Register of Historic Places and listed as “endangered” by the World Monuments Fund — was demolished.

In Southern California’s overheated real estate market, Neutra houses can carry outsize price tags, evidence of their significance and desirability. Even so, an alarming number of them have been bought as teardowns. “There should be a national will to save these buildings,” Neutra told The Times in 2004. “It shouldn’t have to be a one-man crusade.”

Dion Neutra was born in Los Angeles on Oct. 8, 1926. “My dad started me drawing when I was 11,” Neutra recalled in 2001. By 1944, Dion Neutra, then a 17-year-old high school junior, was identified by the Magazine of Architecture as a collaborator with his famous father.

After service in the United States Navy during World War II, Neutra pursued his architecture studies at USC, graduating in 1950. Neutra then went to work in his father’s firm. Accolades came quickly: a First Honor award from the American Institute of Architects in 1954, followed by an AIA Merit award the following year.

Father and son worked together through the 1950s amid patches of turbulence. In 1961, Dion Neutra described “frustration, resentment and distortion” in the relationship. After a brief split, they were again joined in practice from 1965 until Richard Neutra’s death in 1970. “Artistically,” his mother said, “they got along very well.”

Some of the tactics Neutra employed in the name of preservation verged on guerrilla theater. In the summer of 2004, he turned up at the Cyclorama Center in Gettysburg with a length of heavy chain, demonstrating how he would attach himself to the building if and when a demolition squad arrived. “I’ll confront the bulldozers and say, ‘Take me with the building, gentlemen,’ ” he proclaimed, as battlefield tourists and broadcast news teams gathered to watch.

After the Cyclorama Center was demolished, the ground where it had stood for 51 years was groomed in emulation of 1863. The aging Neutra did not, in the end, chain himself to the building.

The loss was also acutely personal. “They become part of who you are,” he said of the buildings he and his father created. “So to take one of those down is like cutting off part of my arm.”

In the early 2000s, after Neutra architecture, and all things midcentury modern, had swung back into vogue, Neutra allowed the licensing of a limited number of Neutra designs — a typeface, furniture, and house numbers — to House Industries.

Asking prices for Neutra homes were on the rise. Neutra found that they had now become fetish objects. He also discovered that the avowed Neutra fans who bought them often had little interest in collaborating with him on restorations, interpreting his overtures as meddlesome or his intentions as worryingly purist. “We keep getting people having their interpretation of ‘what Neutra would have wanted,’ ” he bristled, “when Neutra is around to be asked.”

Neutra maintained a studio in his Silver Lake home, the Reunion House, designed by his father in 1950. From there, he served as executive consultant and project director of the Neutra Institute for Survival Through Design, a nonprofit foundation established in 1962 to advance modernist and ecological principles, and wrote several books, including a self-published memoir in 2017. The nearby Neutra Office Building, at 2379 Glendale Blvd., was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2004.

Neutra’s final project was a house in Honduras for the younger of his two sons, Nick Neutra, completed in 2018 and the subject of a 2017 documentary short, “Neutra in Roatan.” In addition to his sons and brother, he is survived by his wife, Lynn Smart Neutra; two grandchildren; one great-grandchild; and two stepchildren from a previous marriage.

Preserving architecture as he did, Neutra admitted, involved risks of its own. “My wife gives me hell because I’ve kept the original 1950s Case toilet that doesn’t flush right,” the architect said of his own house. “’Listen,’ I tell her. ‘This is the toilet that Richard Neutra sat on — I’m not getting rid of it.’”

Rozzo is a special correspondent

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.